c. 2008 Religion News Service

(UNDATED) The request was an odd one, coming from Norman Lee Toler.

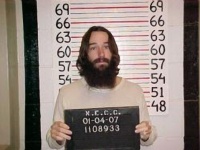

Toler, then 25, had spent most of his adult life in prison on charges ranging from writing bad checks to statutory rape. It was that last conviction that landed him in the Northeast Missouri Correctional Center, where he identified himself as Jewish, and, in 2005, first requested a kosher meal.

But Toler, corrections officials argued, was a white supremacist who earlier had been reprimanded by prison official in Illinois for keeping seven photos of Adolf Hitler and a hand-drawn illustration of a Nazi skinhead in his cell.

When his request for kosher meals was denied, Toler filed a lawsuit in federal court, alleging that authorities were jeopardizing his health and impeding his ability to practice Judaism.

Three years later _ and six years after he claimed to have converted to the faith _ a federal court ruled in his favor.

Toler’s case, while exceptional, reflects the murky legal landscape of First Amendment law. Faced with similar litigation about prisoners’ free exercise rights, states are being forced to revisit their kosher meal policies.

Under the terms of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA), prisons can gauge only the sincerity, not the validity, of an inmate’s religious beliefs _ and must try to accommodate them.

As a result, prisoners nationwide are using the federal law to ask for everything from prayer beads to sweat lodges _ and increasingly kosher meals _ with varying degrees of success.

With the recent widening of civil laws, the distinction between who is Jewish and who is not is sometimes lost.

Gary Friedman, chairman of Jewish Prisoner Services International, and a prison chaplain in Washington state, estimates that at least 20,000 U.S. inmates falsely identify themselves as Jews. That group can include non-ordained Jews, Messianic Jews and scam artists looking for pocket money and, in some cases, a pathway to Israeli citizenship.

The No. 1 issue, he says, is security.

“A lot of (high-security inmates) are mentally ill. And they have a rampant paranoia about their food being poisoned,” Friedman said. “So what happens is the kosher meals are pre-packaged and sealed, so they think it’s safer.”

Friedman says their motives are rarely genuine. He cited examples of prison gangs using Judaism as a front to hold group summits, and inmates hoping to take advantage of wealthy Jewish philanthropists.

(BEGIN FIRST OPTIONAL TRIM)

“My favorite one was a guy who wrote every single Jewish organization … soliciting $50,000 from each of them so that his tennis-playing buddy, who’s about to get out of prison, could run around the country playing tennis and promoting Judaism by wearing the Star of David on his tennis shorts,” Friedman said.

(END FIRST OPTIONAL TRIM)

Rabbi Menachem Katz, director of prison programs for the Aleph Institute, said Friedman’s figure seems excessive. Katz, whose organization provides prayer books and religious items for prisons, estimated that just 10 percent of all requests he receives come from non-Jews.

Inevitably, he said, some will slip through the loopholes and receive the more expensive kosher meals. “It bothers me as a taxpayer maybe,” Katz said, “but not as a rabbi.”

Because there is no nationwide policy on kosher meals, the cost to the taxpayer varies from state to state, and even from prisoner to prisoner.

In Missouri, for example, Toler’s kosher meals cost, on average, more than three times the price of a regular prison meal. But that difference is minimal since Toler is the only inmate who receives the special meals. (The state is currently reviewing its policy in response to the court’s decision.)

Colorado taxpayers pay a far heftier price. Kosher meals cost the state $2,500 per year, per prisoner _ more than double the $1,100 cost of feeding a non-Jewish inmate.

For Colorado’s 23,000 inmates, the difference between, say, Wicca and Judaism can be reduced to a piece of paper. Inmates receive a religious diet application upon arrival at a prison, and can change their affiliation just once each year.

According to Katherine Sanguinetti, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Department of Corrections, five to 10 prisoners violate the policy each month. Inmates who receive kosher meals are on a two-strike policy _ if they are caught eating non-kosher food once, they are put on probation. If it happens twice, they are taken off the diet.

“We really tried to accommodate all faiths and all beliefs,” Sanguinetti said. “And as long as something did not breach security in some way, we allow it.”

But Friedman says such policies are subject to selective non-enforcement. When prisons serve particularly appetizing _ and decidedly un-kosher _ meals such as cheeseburgers, many inmates will abandon their kosher diet for the day.

“Corrections staff, they don’t want to play kosher cop,” Friedman said. “They’ve got other things to do.”

Lori Windham, legal counsel for the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, said the flare-up in the number of kosher meals cases can be attributed in part to RLUIPA. While prisons were previously given the benefit of the doubt in free exercise cases, they now must prove a compelling interest to withhold accommodations.

(BEGIN SECOND OPTIONAL TRIM)

Despite the new regulations, the law is far from one-sided. States can and do find ways to adapt and, when pressed, prove a compelling interest to restrict religious practices.

Florida, for example, discarded its costly kosher meals program in favor of wider-reaching vegan and vegetarian options. The state recently survived a legal challenge from a Seventh-day Adventist who requested kosher meals. The court deemed the state’s existing program sufficient, citing the “excessive cost” and “administrative and logistic difficulties” of providing special meals.

(END SECOND OPTIONAL TRIM)

Windham said the broad free exercise guidelines that Friedman views as problematic are a necessary risk.

“Our position is that we would rather see a few insincere people get through the system than prohibit kosher meals from people who require them,” she said.

KRE/PH END MURPHY1,050 words, with optional trims to 875

A mugshot of Norman Lee Toler is available via https://religionnews.com.