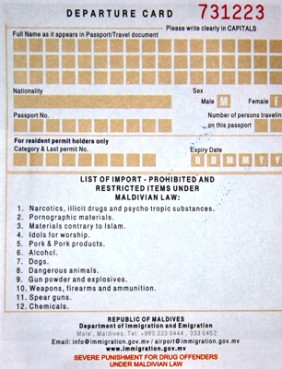

(RNS2-OCT14) A customs form for entry into the Maldives prohibits “materials contrary to Islam” since the country considers itself 100 percent Islamic. For use with RNS-MALDIVES-ISLAM, transmitted Oct. 14, 2010. RNS photo by Vishal Arora.

MALE, Maldives (RNS) Can a nation that considers itself 100 percent Muslim also be a democracy without risking its Islamic identity and ideals?

That’s what this tiny island nation off the southern coast of India is trying to do. Two years after the country embraced democracy, a literary festival imported from the West shows the promise — and peril — of that experiment.

This weekend (Oct. 14-17), the Maldives will host the Hay Festival of Literature and Arts, originally a Welsh event that has branched out to other countries, including Lebanon, Kenya and now, the Maldives.

President Mohamed Nasheed, a moderate Muslim who has won Western acclaim for his environmental activism, offered his retreat island, Aarah, as the Hay Festival venue; the festival plans to return in 2011 and 2012.

Every year, an estimated 700,000 tourists flock to this postcard-perfect chain of about 1,100 islands. Before they can hit the beach, however, they must complete a customs form that includes a list of “prohibited and restricted” imports, including “materials contrary to Islam,” “idols for worship,” pork products and alcohol.

The Hay festival — which Bill Clinton once described as “the Woodstock of the mind,” will also face rigid religious censorship, project director Andy Fryers said. British novelist Ian McEwan, Chinese author Jung Chang and other speakers have been briefed on the censorship laws.

The restrictions are lingering vestiges of the 30-year rule of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, a conservative authoritarian who yielded power in the country’s first democratic elections in 2008.

Yet even with the change in government, there’s been little desire for a change in policy on religious restrictions.

The Protection of Religious Unity Act of 1994 outlaws the promotion of anything that represents a religion other than Islam, or any opinion that disagrees with Islamic scholars. It also prohibits use of any media to speak against the tenets of Islam.

While a new 2008 constitution provided for elections, separation of powers and a bill of rights, it also enshrined the principles of Shariah, or Islamic law, and stated that “a non-Muslim may not become a citizen of the Maldives.”

As a result, all Maldivian citizens are deemed Sunni Muslims, and citizens are reluctant to challenge that assumption — the only two who did paid a heavy price.

Last May, 38-year-old Mohamed Nazim was attacked after he publicly declared his disbelief in Islam. When he sought police protection, he was arrested. Five days later, he read a declaration of the Muslim faith on national television and was released.

Later, Nazim told Minivan News, a Maldivian news website, that many Maldivians were “depressed” and “collapsing inside under the weight of the silence enforced on their questions of belief in Islam.”

“Both the state and non-state agencies need to, at the very least, acknowledge that there are a substantial number of Maldivians who think about their faith and, sometimes, question it,” he said.

Two months later, 25-year-old Ismail Mohamed Didi committed suicide inside the control tower of Male International Airport where he worked. He was reportedly hounded by colleagues, friends and family for expressing doubts on Islam.

To be sure, the Maldives is not the only Muslim-majority country to enshrine Islamic law in civil statutes. But its geographical isolation and small size make policy implementation easier, and perhaps harder to change.

Azima Shakoor, former attorney general and member of the 2008 constitution drafting committee, said rights must never rise above or replace the nation’s official faith.

“I studied in the U.S. but I don’t think the (religious) freedom should be given (to the citizens),” said Shakoor, a member of the main opposition party, led by Gayoom.

Advocating for individual rights is seen as a Western import that threatens Islam. Abdulla Yameen, another opposition leader and Gayoom’s half-brother, said, “We do not want to give the right to establish churches.”

BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM)

There hasn’t been much appetite for change in the country’s politically splintered parliament. Nasheed’s moderate Maldivian Democratic Party lacks an outright majority, and coalition partners remain resistant to change.

The coalition partner Adhaalath Party, which controls the government’s Ministry of Islamic Affairs, rejected a new mixed-gender education policy as “a failed Western concept inconsistent with the teachings of Islam.” In June, opposition parties tried to sack the education minister for proposing that Islam and the national Dhivehi language no longer be mandatory for senior students.

Nasheed’s governing party seems open to some reform, but lacks the necessary votes. “A proper review and study need to be made” on reforming the religious restrictions, said MDP chairperson Mariya Didi.

(END OPTIONAL TRIM)

Political observers say democracy and Islam can co-exist peacefully side by side, but the right to choose leaders should also mean the right to choose faiths.

“There is nothing against democracy in Islam and therefore it is possible for a 100-percent Muslim nation to have democracy –but not when people are forced to be Muslim,” said Asghar Ali Engineer, who chairs the Center for Study of Society and Secularism think tank in Mumbai, India.

“For a liberal secular democracy, the freedom of conscience is the most fundamental. A genuine faith in Islam has to be voluntary.”