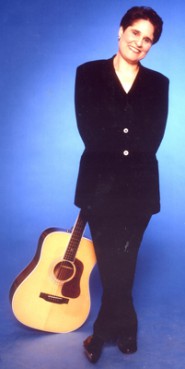

(RNS4-JAN10) Singer folk singer Debbie Friedman died Jan. 9 at age 59. Friedman was instrumental in modernizing Jewish liturgy in ways that were more accessible and inclusive of lay audiences. For use with RNS-DIGEST-JAN10, transmitted Jan. 10, 2010. RNS photo courtesy DebbieFriedman.com.

(RNS) Worship inside many American synagogues used to be, in a word, boring.

Until a generation ago, the congregation had little to no participation in the service, trapped between a professional choir that smothered worshippers with unsingable musical selections and a rabbi who read nearly all the prayers.

Calling it a passive experience would be generous.

The music could be particularly painful — liturgical imports that mimicked the classical stylings of European baroque, or pompous cantors whose operatic-like arias were rooted in the somber tones and bitter history of Eastern Europe.

And then along came Debbie Friedman.

Friedman, who died Sunday (Jan. 9) at the tender age of 59, grew up listening to legendary folk singers including Peter Yarrow, Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. After she picked up her guitar, American Jewish life would — thankfully — never be the same.

Surprisingly, Friedman could not read music, but neither could Irving Berlin, another acknowledged Jewish master of American popular music. She taught herself to play the guitar, and the texts and prayers she set to music permanently shattered the staid inert life of American Jewish worship.

Not surprisingly, at first some rabbis and cantors dismissed her music as shallow. But Friedman triumphed because her “superficial” music had an unlikely ally: the thousands of young Jewish campers in the 1970s and 1980s who sang her songs around countless bonfires.

My daughter (now a rabbi herself) was one of those young campers who felt the emotional and religious power of Friedman’s many compositions; they are the same ones my granddaughter now sings at her summer camp.

When the young campers returned to their synagogues, they demanded Friedman’s music be included in the “adult” services. When those same campers assumed leadership positions in the American Jewish community, they brought Friedman’s music with them. The ballads and melodies once rejected as hollow became a key component of services, conventions and other public assemblies.

Some have compared Friedman to Edith Piaf, the French chanteuse whose artistry, like Friedman’s, also brought audiences to tears. While Piaf sang about romantic love, regret and loss, Friedman sang about the joy of spirituality and the love for her people and all humanity.

Scholars and music critics will no doubt analyze Friedman’s music for its theology or musical quality. But in many ways, none of that matters. The verdict has already been reached. Friedman was an authentic original who, like the Psalmist King David, is already a revered “sweet singer in Israel.”

The reason for her success and acceptance is obvious. A person, even someone born with tin ears, can easily and fervently sing her melodies. Friedman transformed biblical and liturgical texts from the original Hebrew into understandable (and singable) English. While out-of-sight professional choirs are on the wane in most synagogues, the visible “people of God” are singing new songs — Friedman’s songs — unto their Creator.

Standing with her guitar in either Carnegie Hall in a solo concert or at an outdoor camp synagogue, Friedman projected a joy and a love of God and Judaism. Her audiences joined in, often in tears.

Even though Friedman no long walks and sings among us, her music lives on.When we seek God’s physical or emotional healing, we listen to her haunting “Mishebayrach,” her most popular compositions. When violence, war, and destruction overwhelm us, we listen to her rendition of “Oseh Shalom,” an ancient prayer for peace. And when we commence a journey or near the end of our earthly lives, Friedman’s “Traveler’s Prayer” goes with us.

Friedman’s earthly sojourn was much too short, but I want to believe she is still singing, albeit to a different congregation.

(Rabbi Rudin, the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser, is the author of the recently published “Christians & Jews, Faith to Faith: Tragic History, Promising Present, Fragile Future.”)