George Will has published an adaptation of the talk on religion and the American Republic he gave at Washington University’s Danforth Center last December, and while it may not be, in Peggy Noonan’s words, “kind of a masterpiece,” it’s certainly worth a read.

Will outs himself as a None, and argues — High Enlightenment Tory that he is — that religion is not necessary for good citizenship but does help democracy flourish. Likewise, he denies that religious belief is entailed in belief in “America’s distinctive democracy — a government with clear limits defined by the natural rights of the governed”; but he thinks that such natural rights will be “especially firmly grounded when they are grounded in religious doctrine.”

If the David Bartons of the world find this unacceptable, I’m sure Will could care less. His bottom line is that, when it comes to a healthy civil society, religious institutions serve a useful mediating purpose. I wouldn’t disagree.

The Trinity College graduate of the Class of 1962 does, however, stumble coming out of the gate, and because it’s a graceful version of a common stumble, I’d like to indulge in a little professorial correction.

After starting with a story about President Eisenhower fishing, golfing, and playing bridge on a national day of prayer, Will turns to the man’s most famous religious remark.

This was not Ike’s first foray onto the dark and bloody ground of the relationship between religion and American public life. Three days before Christmas in 1952, President-elect Eisenhower made a speech in which he said: “Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” He received much ridicule from his cultured despisers for the last part of his statement — the professed indifference to the nature of the religious faith without which our government supposedly makes no sense. But it is the first part of his statement that deserves continuing attention.

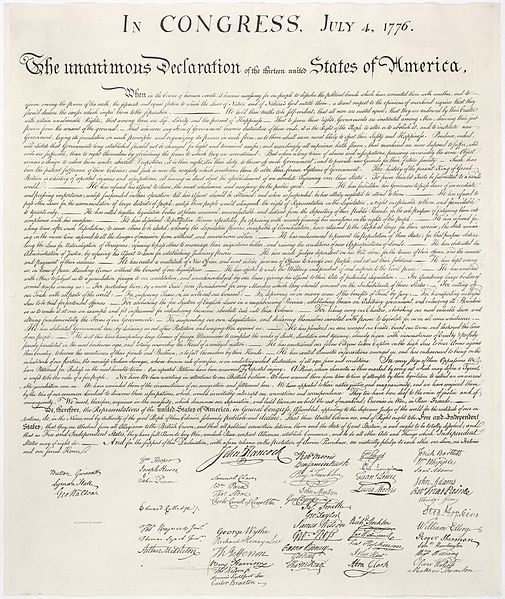

Certainly many Americans — perhaps a majority — agree that democracy, or at least our democracy, which is based on a belief in natural rights, presupposes a religious faith. People who believe this cite, as Eisenhower did, the Declaration of Independence and its proposition that all of us are endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights.

Actually, the cultured despiser who first called attention to Ike’s “and I don’t care what it is” remark was Will Herberg, the Communist-turned-religionist who in his celebrated Protestant Catholic Jew (1955) singled it out not for reproach but for approval in pretty much the same way that Will approves of religion. To be sure, the remark is commonly sniffed at for epitomizing civil religious indifference to actual religious doctrine. But here Will and most other commentators have been led astray by Herberg’s partial quotation.

As the biblical scholar Patrick Henry discovered after painstaking research in 1981, Ike was telling a story about the difficulty he once had explaining democracy to the Soviet general, Marshal Zhukov. “In other words,” he told his audience, “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is. With us of course it is the Judeo-Christian concept but it must be a religion that all men are created equal. So what was the use of me talking to Zhukov about that. Religion, he had been taught, was the opiate of the people.”

Eisenhower did not, in other words, profess indifference to the nature of the religious faith without which our government supposedly makes no sense. He declared that there must be religious faith in the proposition that all men (people) are created equal. For people rooted in a religious tradition that subscribes to that proposition, democracy “has sense.” Their faith was a matter of indifference only in other respects.

Of course, the signers of the Declaration of Independence themselves held the proposition to be a self-evident truth, i.e. no religious faith necessary. Self-evident or not, what concerned Eisenhower was democracy’s need for belief in fundamental human equality — that all are so “endowed by their Creator,” as he said, “not by the accident of birth, not by the color of their skins or by anything else.”

At Trinity, Will is still remembered for publicly resigning from a fraternity that refused to admit blacks and Jews. Now, preoccupied as he is with belief in limited government, he fails to apprehend that that’s what Ike was talking about.