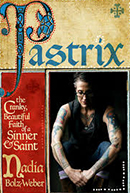

Nadia Bolz-Weber, an unconventional Lutheran pastor talks about her salty, provocative spiritual memoir.

Nadia Bolz-Weber is not your typical pastor. She’s plastered in colorful tattoos, says she wishes she weren’t a Christian, and cusses with impunity. But her ability to wield words with perspicacity is giving Bolz-Weber a growing platform among Christians. Her new memoir, Pastrix: The Cranky, Beautiful Faith of a Sinner & Saint, released this week in Amazon’s top 100, and she has been featured in The Denver Post, Christian Century, Huffington Post, Sojourners and on NPR. She is also the founding pastor of House for All Sinners and Saints, an Evangelical Lutheran (ELCA) church in Denver, Colorado. Here, we discuss her calling, church, and struggle to believe that the gospel is true and redeeming.

JM: In your pre-pastoral life, you were a stand-up comic. What sort of similarities and differences have you found in these “communicator” roles?

NBW: I think that both comics and preachers view reality from a very particular perspective. And I think that as comics, we see everything from the underside of the psyche. In some ways, to be a good preacher, you have to be able to do the same. It doesn’t mean you have to be funny, but it does mean that you have to have the capacity to tell the truth, but tell it slant.

JM: You’re something of a misfit pastor, and you seem to embrace this identity. In your book, you talk about your unusual call to ministry. Can you tell us about that?

NBW: That’s literally the book. I left the fundamentalist Christianity of my youth when I was a teenager and spent a decade outside of the church quite literally hating Christianity. When I returned to it, I came back to a very particular tradition that had an articulation of the gospel and a liturgical tradition that put language to things I had already experienced to be true in my life. So, despite the fact that in some ways I’d rather be something besides a Christian, I cannot deny the experiences in my life of a surprising and unexpected and destabilizing God.

To not confess that would be to deny what I’ve experienced in my life. So I have no other choice.

JM: But was there a particular moment when you sensed God’s call?

NBW: My call to ministry, quite literally, happened in a comedy club. A friend of mine had committed suicide—this was years before I ever went to seminary—and everyone turned to me and said, “Well, you’ll do the funeral, right?” Because I was the religious one. And giving his eulogy, I looked out at this room of hundreds of people–comics, academics, queers–and I realized that I felt called to be a pastor to my people. I thought, “These are my people,” and I felt called to be a pastor to my people.

JM: With what I might call “disarming honesty,” you describe yourself as misanthropic and willing to walk away if you see a needy person coming at you. This seems to be to place you at odds with your role as a pastor. How do you reconcile the two?

NBW: I think God wants God’s people to be cared for, and I believe God has done that “Grinch” thing with my heart and made it a couple sizes bigger. And I do love the people in my care. That does not, however, extend to all of humanity. I don’t naturally necessarily care about everyone else’s stories. I don’t have a heart for all people, like some others do. I just have a heart for my people.

JM: You founded a congregation, The House For All Sinners and Saints. How is it like or unlike other Lutheran churches?

NBW: We’re more liturgically traditional than most other Lutheran churches. So that’s, sort of, counterintuitive for some people. But how we do it is completely different. We’re in the round. Different parts of the liturgy are led by 15 or 18 different people. It’s not centered on the pastor. And we have a time right after the sermon, usually 10 minutes, to pray and reflect and respond. And that’s when people write “the prayers of the people” for later in the liturgy. So there’s an intimacy to how we live our liturgical life together. We always sing Southern gospel hymns, and we’re acapella. So we sing Fanny Crosby hymns, stuff like that. But then we’ll do acapella Gregorian chant liturgy. It is a bizarre combination.

JM: You’ve mentioned the inner struggle between reading the Jesus story as fairy tale and as the story that is true and redeeming. I accept the gospel as truth, and I can’t imagine the impact that living in that tension would have on my faith. Can you give us a glimpse of what your faith looks like on a bad day and on a good day?

NBW: I don’t know. My faith is the same on bad days and good days. It’s all kind of marginal. God gives different people different gifts. And I think I was given the gift of faith. So, it doesn’t mean that I have this naïve everything-that-happens-in-the-Bible-is-historical-and-scientific-fact type of faith. But I’ve never managed to be an atheist, even on my worst days. I might be furious at God, or I might feel alienated from God, but I’ve never managed to think that God was not there. I think the practice of Christianity is what I struggle with more than the faith of it.

*Below is the book trailer for Pastrix. Please be advised that this video contains language some viewers may find objectionable: