I’ve been thinking lately about how various people respond to criticism, and how easy it is to lash out in an immature fashion when we feel we have been unfairly judged or even attacked.

I’ve been thinking lately about how various people respond to criticism, and how easy it is to lash out in an immature fashion when we feel we have been unfairly judged or even attacked.

I used to be a good deal more hotheaded than I am now; just ask my family about this. But any serenity I’ve acquired here in my 40s is mostly because I learned the hard way that kneejerk reactions made me feel like, well, a jerk. Over time [tweetable]I’ve developed three basic rules that govern how I respond to unfair judgments or accusations.[/tweetable]

When I feel wronged, I:

1) Wait 24 hours before responding.

If the judgment happens in writing, either through an angry email (like the evangelical Christian who wrote this week to accuse me of violating God’s sacred word with The Twible) or a blog comment, waiting 24 hours is easy enough to do. [tweetable] Although many of us tend to respond to inflammatory online statements with immediate tongue-lashings in kind, this is not a healthy way to live.[/tweetable]

A 24-hour cooling off period has been the single most effective way for me to keep my anger—and my wounded ego—in check as I formulate a response. That’s harder to do when an unjust accusation occurs in person, to my face. That situation doesn’t happen often (isn’t it interesting that people who would say just about any nasty old thing to you online would rarely consider saying those same things to you personally?) but it’s surprising how much better things proceed if I simply say, “Why don’t we regroup and talk about that tomorrow?” and then respond in writing.

2) Limit a response to no more than five sentences—or feel free to ignore the original comment entirely.

I’ve noticed online that when we feel attacked, many of us feel tempted to match our more aggressive interlocutors point for point, going into exhaustive detail about how of course our accuser in question is wrong and of course they haven’t researched X or Y subject in any detail, etc. Maybe those assumptions are true and maybe they aren’t (see point #3), but [tweetable]try considering brevity the soul of maturity in responding to unfair accusations.[/tweetable]

Limit your response to no more than five sentences, tops. And think seriously about whether it will do any good to respond at all. If you do respond, will you be contributing to a better understanding of the subject, or just smoothing your own ruffled feathers? Are you responding in anger, in order to wound as you have been wounded?

3) Consider ways that your critic might be right.

Yeah, I know this is the hardest advice of all to swallow, and while I’ve made significant strides with my own advice on points #1 and #2, I’m not very good at this last one. But I know it is important counsel for me to adopt as I try to develop into the person I want to become. So I try to remind myself: Just because someone is acting like a total jerk to me doesn’t mean what that person is saying about me is automatically wrong. We can learn so much from our harshest critics, who teach us where our logic is flawed and our understanding limited.

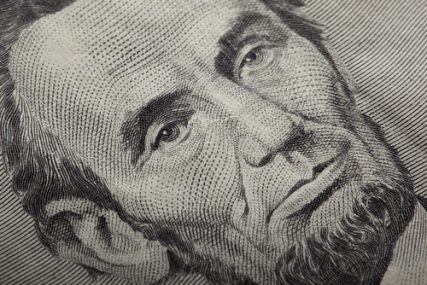

This week I had an important reminder of this last point, as drawn from the life of Abraham Lincoln. Throughout his career, [tweetable]President Lincoln found ways to rise above personal criticism, avoid holding grudges, and even (gulp) add critics to his inner circle.[/tweetable] On Wednesday night I went to hear historian Doris Kearns Goodwin speak, and among the many fascinating things she said during that stimulating evening was to remind her Cincinnati listeners of an event that happened right here in our city that proved the mettle of Lincoln’s magnanimous character.

This week I had an important reminder of this last point, as drawn from the life of Abraham Lincoln. Throughout his career, [tweetable]President Lincoln found ways to rise above personal criticism, avoid holding grudges, and even (gulp) add critics to his inner circle.[/tweetable] On Wednesday night I went to hear historian Doris Kearns Goodwin speak, and among the many fascinating things she said during that stimulating evening was to remind her Cincinnati listeners of an event that happened right here in our city that proved the mettle of Lincoln’s magnanimous character.

When Lincoln was still an unknown circuit lawyer in Springfield, Ill., he was tapped to help in a patent case being tried in Chicago. The inventor’s legal team wanted an Illinois man who understood Illinois law, so despite some misgivings, they put Lincoln on retainer. He was delighted and worked during the entire summer of 1855 to develop his case.

However, the trial venue was moved from Chicago to Cincinnati, and the fancy lawyers never bothered to let Lincoln know that his services were no longer needed. When he arrived in Cincinnati for the trial, they snubbed him completely, with lead attorney Edwin Stanton haranguing a colleague about bringing in a “long armed Ape” who “does not know any thing.”

Stanton and the other attorneys ignored Lincoln’s suggestion that they all walk over to the courthouse together, and they left without him. During the week of the trial, they did not even consult the lengthy brief Lincoln had spent the summer preparing, never asked him to join them for a meal at the hotel where they were all staying, and passed him over for a dinner party to which every other lawyer working both sides of the case had been invited.

What was Lincoln’s response to this? He was enthralled to see such brilliant lawyers at work. He came to court every day and listened to the arguments with “rapt attention.” He was particularly impressed by Stanton, the attorney who had shamed him in that unforgettably junior high-ish way.

Here is how it turned out:

Unimaginable as it may seem, after Stanton’s bearish behavior, at their next encounter six years later, Lincoln would offer Stanton “the most powerful civilian post within his gift”—the post of secretary of war. Lincoln’s choice of Stanton would reveal . . . a singular ability to transcend personal vendetta, humiliation, or bitterness. As for Stanton, despite his initial contempt for the “long armed Ape,” he would not only accept the offer but come to respect and love Lincoln more than any person outside of his immediate family.” (Team of Rivals, 173-175)

Could I have done what Lincoln did, and responded to intentional disgrace with such maturity and dignity? Nope. But, inspired by Lincoln’s example, I am resolved to do better.

Three rules for responding to critics (thank you, Abe Lincoln!)

It's easy to lash out in an immature fashion when we feel we've been unfairly judged. I've got three strategies for dealing with this, the last one inspired by President Lincoln.

I used to be a good deal more hotheaded than I am now; just ask my family about this. But any serenity I’ve acquired here in my 40s is mostly because I learned the hard way that kneejerk reactions made me feel like, well, a jerk. Over time [tweetable]I’ve developed three basic rules that govern how I respond to unfair judgments or accusations.[/tweetable]

When I feel wronged, I:

1) Wait 24 hours before responding.

If the judgment happens in writing, either through an angry email (like the evangelical Christian who wrote this week to accuse me of violating God’s sacred word with The Twible) or a blog comment, waiting 24 hours is easy enough to do. [tweetable] Although many of us tend to respond to inflammatory online statements with immediate tongue-lashings in kind, this is not a healthy way to live.[/tweetable]

A 24-hour cooling off period has been the single most effective way for me to keep my anger—and my wounded ego—in check as I formulate a response. That’s harder to do when an unjust accusation occurs in person, to my face. That situation doesn’t happen often (isn’t it interesting that people who would say just about any nasty old thing to you online would rarely consider saying those same things to you personally?) but it’s surprising how much better things proceed if I simply say, “Why don’t we regroup and talk about that tomorrow?” and then respond in writing.

2) Limit a response to no more than five sentences—or feel free to ignore the original comment entirely.

I’ve noticed online that when we feel attacked, many of us feel tempted to match our more aggressive interlocutors point for point, going into exhaustive detail about how of course our accuser in question is wrong and of course they haven’t researched X or Y subject in any detail, etc. Maybe those assumptions are true and maybe they aren’t (see point #3), but [tweetable]try considering brevity the soul of maturity in responding to unfair accusations.[/tweetable]

Limit your response to no more than five sentences, tops. And think seriously about whether it will do any good to respond at all. If you do respond, will you be contributing to a better understanding of the subject, or just smoothing your own ruffled feathers? Are you responding in anger, in order to wound as you have been wounded?

3) Consider ways that your critic might be right.

Yeah, I know this is the hardest advice of all to swallow, and while I’ve made significant strides with my own advice on points #1 and #2, I’m not very good at this last one. But I know it is important counsel for me to adopt as I try to develop into the person I want to become. So I try to remind myself: Just because someone is acting like a total jerk to me doesn’t mean what that person is saying about me is automatically wrong. We can learn so much from our harshest critics, who teach us where our logic is flawed and our understanding limited.

When Lincoln was still an unknown circuit lawyer in Springfield, Ill., he was tapped to help in a patent case being tried in Chicago. The inventor’s legal team wanted an Illinois man who understood Illinois law, so despite some misgivings, they put Lincoln on retainer. He was delighted and worked during the entire summer of 1855 to develop his case.

However, the trial venue was moved from Chicago to Cincinnati, and the fancy lawyers never bothered to let Lincoln know that his services were no longer needed. When he arrived in Cincinnati for the trial, they snubbed him completely, with lead attorney Edwin Stanton haranguing a colleague about bringing in a “long armed Ape” who “does not know any thing.”

Stanton and the other attorneys ignored Lincoln’s suggestion that they all walk over to the courthouse together, and they left without him. During the week of the trial, they did not even consult the lengthy brief Lincoln had spent the summer preparing, never asked him to join them for a meal at the hotel where they were all staying, and passed him over for a dinner party to which every other lawyer working both sides of the case had been invited.

What was Lincoln’s response to this? He was enthralled to see such brilliant lawyers at work. He came to court every day and listened to the arguments with “rapt attention.” He was particularly impressed by Stanton, the attorney who had shamed him in that unforgettably junior high-ish way.

Here is how it turned out:

Could I have done what Lincoln did, and responded to intentional disgrace with such maturity and dignity? Nope. But, inspired by Lincoln’s example, I am resolved to do better.

Donate to Support Independent Journalism!