Michael De Dora is director of CFI’s Office of Public Policy and represents CFI at the United Nations. He heads CFI’s Campaign for Free Expression, which launched in 2012 to increase public awareness of threats to this fundamental right.

Sensational headline alert! “Band of heathens” is … strong. But the good-humored folks at the Center for Inquiry (CFI) know the benefits of an enticing lead. Now that I’ve got your attention, go ahead and read what CFI is doing to ensure that everyone, regardless of faith, has the right to free expression.

Michael DeDora is director of CFI’s Office of Public Policy and represents CFI at the United Nations. He heads CFI’s Campaign for Free Expression, which launched in 2012 to increase public awareness of threats to this fundamental right. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Brian Pellot: Why did CFI decide to tackle the issue of free expression?

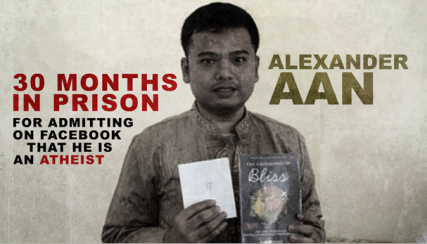

Michael DeDora: The campaign really started with Alexander Aan. Back in 2012, we learned of this case in Indonesia where a young man had been arrested for posting on Facebook that he was an atheist along with cartoons and criticisms of Islam. CFI has been represented at the United Nations since 2006, so we spend a lot of time monitoring cases of persecution where people are harassed, arrested or jailed for criticizing religion. There was something about the Aan case that was particularly disturbing for us. He had been raised in a religious household and was going through the very basic process of questioning religion. He was looking on Facebook for other people going through the same process in Indonesia. An angry mob showed up, dragged him outside, and when police came, they arrested Aan because he had blasphemed. The idea that this could have happened to me in a different setting was maddening and really depressing. He was just looking for information.

Once that case came onto our radar, we started paying closer attention to cases of people being persecuted for stating their faith or atheism or for exerting their right to freedom of expression. We’ve continue to add cases from Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and more countries, allowing people to see that this is an ongoing and global problem.

BP: What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in taking on this campaign?

MD: Some countries’ laws around this issue are based on religion, whereas others are based more on control. When people are prosecuted for blasphemy or insulting religious sentiments, it’s hard to know what the real motivation is. The biggest challenge I’ve found is getting reliable information. Crackdowns on freedom of expression occur most frequently and most severely in non-English-speaking countries, and not everyone in the world is walking around with an iPhone and Wi-Fi to document abuses.

When we do get information, very often we find that blasphemy cases arise for purposes other than punishing actual blasphemy. In Pakistan, we’ll hear of someone charged with blasphemy when really a Muslim community is just unhappy that a Christian community moved in next door. They’ll accuse them of blasphemy, an uproar will ensue, and Christians will have to relocate for their own safety. It’s often difficult to know from the U.S. what’s really happening on the ground.

BP: Have you noticed any commonalities in the cases you’re tracking across different countries and contexts?

MD: Blasphemy cases often get filed by disgruntled people saying, “so-and-so said something bad about God and the police need to investigate.” The investigations that follow are often ridiculous. In many cases, evidence of blasphemy can’t even be presented in courts because that in itself would be blasphemous.

I’m also starting to more convictions and persecutions based on language that sounds more legalistic than blasphemy. When Alexander Aan was being put through Indonesia’s criminal justice system, they charged him with a range of different crimes, including lying on a government I.D. card. In Indonesia, you need to belong to one of six religions. His I.D. said he was a Muslim, but then he declared that he’s an atheist, which isn’t an option. He was also charged with blasphemy and inciting religious hatred—“inciting” the mob that came and beat him up. Russia is doing this now too, saying no religious sentiments should be hurt. That’s disturbing to me.

One reason why countries use terms like “inciting religious hatred” is because this language exists in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, so countries can in theory point to international law and say, “we’re complying.” The U.N.’s special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief Heiner Bielefeldt and people at the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights are catching on to this. That’s not what the covenant was intended to allow. It was aimed at violent incitement, like someone preaching that people in the town next door should be killed immediately, not at someone saying, “Hey, I’m an atheist.” The Rabat Plan of Action clarified that language in the covenant is not to be used to punish blasphemy and thought crimes. That’s progress.

BP: Many Christian groups say their faith is the most persecuted in the world. How does Christian persecution compare to that of atheists?

MD: Every day I get email updates about bills proposed in the House and Senate. About once a week it seems I’ll see a Republican propose a resolution specifically acknowledging the persecution of Christians and saying the U.S. should do more to stop it. We’ve lobbied with the offices proposing these measures to include examples of atheists, skeptics and humanists being persecuted and have almost universally been turned down.

There’s no doubt that Christians are persecuted around the world. Some of the case we track are of Christians. But there’s also really bad persecution taking place against non-religious people. One of the difficulties in showing this is that laws and cultural norms prohibit the formation of atheist communities in many societies. When a whole community of Christians is persecuted or killed in riots or has to relocate in Egypt, Pakistan or Afghanistan, that’s an easy thing to see. When it comes to atheists, more often we only have individual cases, so it’s easy for people to write that off.

It’s difficult to compare how bad it is for Christians and atheists around the world, but I think it’s important to think about. Christians have been persecuted, but in most cases they have still been able to build communities and to huddle together. In those same places, if you stand up and say, “I’m an atheist,” you might be in trouble.

BP: How do you think religious freedom and freedom of expression overlap or conflict?

MD: At the U.N., we work with groups like the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty where, when it comes to religious freedom in America, we disagree on many things. At the U.N. we all agree that blasphemy laws are bad, but in the U.S., some Christian groups think the contraceptive mandate and gay marriage are bad, whereas we think they’re okay. There’s certainly some tension there, and an acknowledgement that groups that work on religious freedom issues internationally often can’t work together domestically. Sometimes your allies on one issue are your strongest opponents on another.

We at CFI don’t see any tension between religious freedom and freedom of expression, but I think that some of the Christian groups that work with us on international freedom of expression issues have a more narrow version of religious freedom within in the U.S. When we work with Becket Fund or when they work with CFI, I know we won’t agree on everything, but I’d like to see us include all different groups in our work. I don’t want to hear from Becket that they’re not concerned about the plight of atheists when we’re concerned about the persecution of Christians, Muslims and Jews.

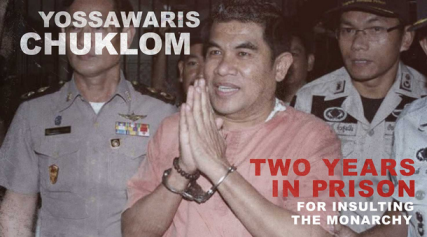

BP: Looking at the cases you track, Yossawaris Chuklom stands out. This prominent comedian and activist was recently sentenced to two years in prison for insulting the monarchy in Thailand. Unlike CFI’s other cases, this one has nothing to do with religion. Why have you included his case in your campaign?

MD: Freedom of expression is not just the freedom to express ideas critical of religion. One thing we’ve had internal debate about is the extent to which we should include people not persecuted for religion, but for expressing ideas that are otherwise unpopular. We focus more on cases related to religion, but we’re also trying to keep in mind that the value of freedom of expression is the ability to say anything. We find any law that restricts the ability of people to speak or to express themselves problematic. When we saw this guy’s case, the idea that someone could be thrown in jail for criticizing the monarchy seemed insane, so we included it.

BP: What successes have you seen since the Campaign for Free Expression began in 2012?

MD: It’s been difficult to track successes. When the Aan case happened, we wrote the Indonesian ambassador to the U.S. and held a protest outside the embassy in D.C. and outside the consular office in New York. When the crackdown on atheist bloggers in Bangladesh happened last year, we held 10 protests over a week. The fact that these governments know we exist and care about someone jailed in their countries and that people are up in arms over in the U.S. is a success, and it’s spreading. There was even a group of of brave people in Bangladesh who protested outside the jail where the bloggers were being held. In the long run, this kind of activism will lead people in positions of power to listen and to address our concerns. Freedom of expression is a right everyone should enjoy, not just atheists and Christians.

BP: You’re CFI’s representative at the United Nations. On Jan. 1, China and Saudi Arabia became members of the U.N. Human Rights Council. Both have terrible records on religious freedom and free expression. What are your thoughts on the council?

MD: It’s unfortunate that countries that restrict human rights are given privileges at the U.N., but it’s a political body. Instead of thinking the whole system is broken, we need to get in there, get our hands dirty and make the U.N. better from within. If we work hard enough with enough groups we can change some things. The reason defamation of religion resolutions are no longer passed is that enough groups and countries were convinced that this was a really bad idea. Maybe we can convince them it’s a bad idea to let countries with bad human rights records into the Human Rights Council, but the only way to do that is through advocacy work. If human rights defenders don’t stand up and speak, nothing will change.

To see all of the cases CFI is tracking and to find out how you can take action, visit CFI’s Campaign for Free Expression page.