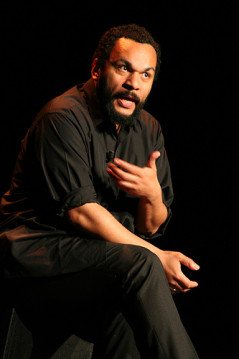

The U.K. Home Office announced yesterday that French comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala has been banned from entering Britain. The decision came weeks after Dieudonné, who has been convicted for hate speech against Jews in France, canceled his nationwide tour when the government banned his opening performance.

Dieudonné had said he would visit Nicolas Anelka, a French soccer player based in England who faces a minimum five-match ban for performing the comic’s trademark “quenelle” gesture, a vaguely anti-Semitic anti-establishment reverse-Nazi salute.

This is hardly the first time a controversial public figure has been barred from Britain’s borders.

In 2009, the Home Office banned anti-Islam Dutch MP Geert Wilders and the Westboro Baptist Church’s infamous head Fred Phelps from entering the U.K.

In June 2013, Britain banned anti-Islam bloggers Pamela Gellar and Robert Spencer, who planned to speak at a far-right English Defence League march near where British Army soldier Lee Rigby was brutally murdered by Islamist extremists.

A government spokesperson justified the decision, saying individuals whose presence “is not conducive to the public good” could be banned from Britain.

As my friend and former colleague over at Index on Censorship Padraig Reidy wrote at the time:

“If these people break the law while in the country, and are prosecuted and barred, whether for hate speech, incitement to violence or relevant criminal offences, then at least it can be said that we are all subject to the same law, and the law has been broken. But this pre-emptive extra-judicial move is a strategy that risks undermining cohesion and entrenching bitterness in an already vicious argument.”

When unpopular speech is suppressed or outright banned, society misses an important opportunity to question and to challenge hateful opinions in the public square.

If Dieudonné were to instruct an anti-Semitic crowd to “go kill the Jews next door,” he’d be inciting imminent violence, which few people or governments would regard as speech worthy of protection.

But to preemptively ban him and other haters from entering Britain or speaking out reinforces divisiveness. It turns them into free speech martyrs. It suppresses the expression of harmful and hateful views held by some members of society, allowing them go unexamined and unchecked.

Barring the clear and present danger associated with incitement to imminent violence, we should let the marketplace of ideas determine the limits of acceptable speech.