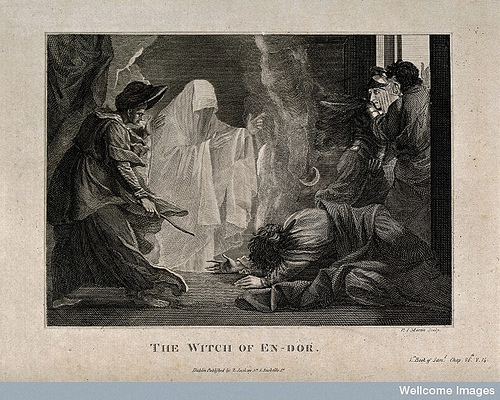

The Witch of Endor, who Saul visited in 1 Samuel. Photo by wellcome images via Flickr (http://bit.ly/1llsS1U)

Today’s Oscar post is only tangentially Oscar-related, which is to say that it is about the kind of movie that will never actually make it to the Academy Awards. Over its 86 years, the Oscars have seen silent films (Wings was the first winner in 1929; The Artist, mostly silent, won in 2012), cartoons (Beauty and the Beast), and 3-D extravaganzas (Avatar). Even Wes Anderson has managed to sneak in a nomination or two, although how anyone likes his stuff is still beyond me. But I digress.

What we’re talking about today is the Christian horror movie. Despite growing up in a Christian home and with a deep and abiding love for horror films, I wasn’t aware of this category of movie until partway through college, when I read an interview with Scott Derrickson about his upcoming film, The Exorcism of Emily Rose. This is an interesting case, as it bridges the gap between legitimate horror movies with religious themes (The Exorcist, Carrie, Night of the Hunter) and horror movies made by Christians to scare people into behaving a certain way. Emily Rose falls more into the former category than the latter—it stars Laura Linney and Tom Wilkinson, and it’s a genuinely well-done film.

As to the other sort of Christian horror movie, we have only to look to a very recent release. The Lock-In, a “found footage” film in the vein of The Blair Witch Project, tells the story of three young boys who bring a pornographic magazine to a church overnight and, in so doing, unleash some sort of demon. (Subtlety is not the genre’s strong suit.) “Heavy-handed” is the kindest phrase I can think of to describe the filmmaking technique, although it sounds like a double entendre, considering the subject matter.

Another film you may have missed at the box office was 2013’s Final: The Rapture. The movie is based on a book by the director, Tim Chey, whose wife compared the film to a Trojan Horse. The movie’s purpose is “to scare the living daylights out of nonbelievers,” Chey told RNS’s Mark Pinsky. “If it means I have to make a horror film to make it realistic to win people to Christ, then so be it.”

And therein lies the problem with the Christian horror genre. (To be clear, and fair, these aren’t popular films among the Christians I know. Most of them would roll their eyes and buy a ticket for Philomena or American Hustle. But the scare tactics filmmakers use to redirect viewers to Christianity are worth a deeper look.)

These directors say that it is important to acknowledge the evil in the world, and I won’t disagree with that. It’s just that these movies are just so terribly done it’s hard to remember what the point was in the first place. This is a world in which violence can be as graphic as the filmmaker wants and demonic spirits abound, but profanity never escapes the lips of a single character. And that’s “realistic.” Some makers of Christian horror films, as in the case of Chey, regularly cite the existence of evil in the Bible as their inspiration. It is well and good to explore that, but when the results of that exploration are as clunky and unartistic as some of these, I have to believe most filmmakers would be better off simply participating in a Bible study.

Chad and Carey Hayes, the writers behind last summer’s The Conjuring, have proudly said they wrote a horror film without “any slashers, no gore, nobody gets killed…And no sex or foul language.” While The Conjuring wasn’t explicitly Christian, its writers were, and so was at least part of its marketing campaign. The film itself was a solid horror movie, with the usual goings-on of a demon-possessed house, but the Hayes’s pride in creating a terrifying world without slashers, gore, or sex doesn’t exactly strike me as praiseworthy. If the goal is simply to make a scary movie, they’ve succeeded. Why do these filmmakers need to tout how “clean” their horror movies are?

What we really might benefit from are filmmakers who leave space for viewers to respond, to imagine, to see the open space before them rather than hitting them over the head with all the subtlety of a 2×4. This is what writers like Shirley Jackson and Flannery O’Connor did so well, although the book as a form allows for more room to play than a film. But when art of any mistakes a message for a story, everyone suffers. (Mua ha ha).