NEW YORK (RNS) Novelist Chaim Potok captured the strain of transition from religious traditionalism to artistic expression in the fictional character Asher Lev. Asher, a young painter prodigy and son of a Hasidic luminary, is drawn to a Brooklyn museum where he surreptitiously views crucifixions and nudes. He then goes on to paint such scenes.

Asher’s mother tries to understand her son’s artistic longings, yet says in exasperation, “Your painting. It’s taken us to Jesus. And to the way they paint women. Painting is for goyim, Asher. Jews don’t draw and paint.”

Asher responds, “Chagall is a Jew,” but his mother cuts him off.

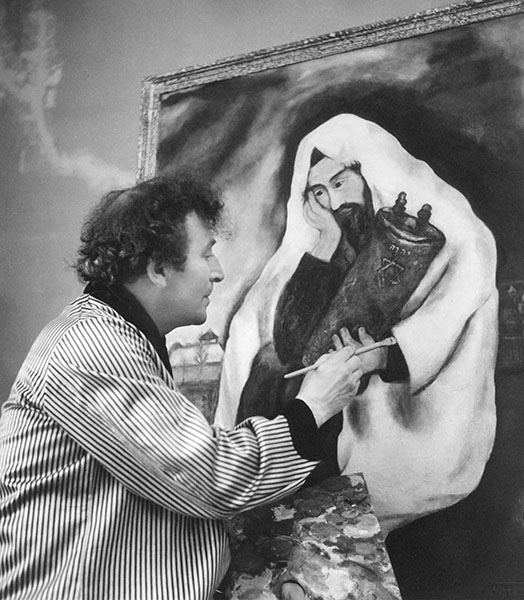

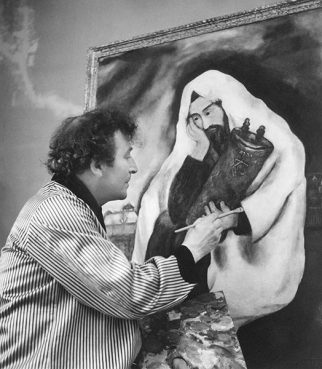

Marc Chagall with Solitude, 1933. Private collection. © Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris. Photo courtesy of The Jewish Museum

“Religious Jews, Asher. Torah Jews. Such Jews don’t draw and paint.”

Returning from a trip to Europe, Asher’s father sees the crucifixion drawings. In a rage, he asks his son if he knows “how much Jewish blood had been spilled because of that man?”

Forty years after first reading “My Name Is Asher Lev,” I have been thinking a lot about the protagonist’s personal and familial struggles. New York’s Jewish Museum recently showcased a critically acclaimed exhibit entitled, “Chagall: Love, War, and Exile.” During the 1930s and 1940s (first in France and then in New York, where he came after being rescued from German-occupied France), Marc Chagall painted Jewish Jesuses as a distraught expression and alarm to the world about the horrific fate of Jews in Europe.

The most popular person on the planet, Pope Francis, is a devoted fan of Chagall, and his favorite is the artist’s “White Crucifixion,” a 1938 painting on display at the Art Institute of Chicago that was not part of the Jewish Museum exhibit.

Chagall painted “White Crucifixion” in France, in response to Kristallnacht. Jesus is on the cross, but his loincloth is a tallit, a Jewish prayer shawl, and he is encircled by scenes of endangered Jews. Chagall may have been simultaneously communicating that the Jew was once again being martyred, and the church’s persecution of Jews in the name of Christ had enabled the Nazi crimes.

Pope Francis greets the crowd as he arrives to lead his general audience in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican on Sept. 11, 2013. Photo by Paul Haring/Catholic News Service

How should we feel about Pope Francis’ embrace of “White Crucifixion?” There is certainly an element of syncretism here, melding Christian and Jewish beliefs. Jesus was, of course, Jewish. And a pope identifying with a crucified Jesus (albeit by a Jewish artist) as a symbol of 20th-century Jewish suffering may be controversial. Also, some Jews might be offended by a Jewish museum exhibiting a collection of Chagall’s Jewish Jesuses. The Jewish Museum demonstrated institutional courage with its Chagall exhibit as well as prescience, unknowingly anticipating a papal connection.

On the other hand, Francis is the first pope to come of age within a Catholic Church transformed through “Nostra Aetate,” the revolutionary 1965 document that moved to end 2,000 years of Catholic enmity toward Jews and Judaism. Francis, a friend of the Jewish people, has reflected on the horrors of the Holocaust and Christian complicity and he would never knowingly be callous toward Jewish sensitivities. Rather than expressing syncretism, he is simply moved by the most instinctual Christian image of suffering — Jesus on the cross — as a means to identify with Jewish suffering. And he is not afraid to express that in a post-“Nostra Aetate” era.

Rabbi Noam E. Marans is the American Jewish Committee’s director of interreligious and intergroup relations. Before joining AJC in 2001, he served for 16 years as rabbi of Temple Israel in Ridgewood, N.J. RNS photo courtesy Rabbi Noam E. Marans

Until Francis says more about his understanding of “White Crucifixion” we are still in the realm of art, not religion or theology. When representatives of the American Jewish Committee met recently with Pope Francis at the Vatican, we presented him a copy of the Jewish Museum exhibit book inside an artistic and inscribed box. We showed him page 105, where a print of “White Crucifixion” is included because of its relevance to the exhibit.

The pope was moved by our recognition of his emotional connection to the painting, and responded with a joyous smile. We, in turn, had the “nachas” (joy) of knowing that we had created a memorable and personal gift for a man who receives thousands of mementos, with an expression of gratitude for the pope’s affection for the Jewish people.

The gesture was another moment in the remarkable journey of Catholic-Jewish relations, which has reached new heights under Pope Francis. He asked us to pray for him as he prepares to visit Jerusalem in May, “so that this pilgrimage may bring forth the fruits of communion, hope and peace. Shalom!”

(Rabbi Noam E. Marans is the director of interreligious and intergroup relations for the American Jewish Committee.)

KRE/AMB END MARANS