Today’s guest post comes from Vlad Chituc, a researcher in a behavioral economics lab at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. The views expressed in this piece belong to Chituc, and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or colleagues.

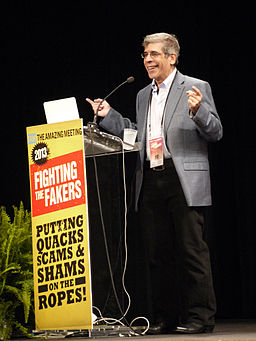

Jerry Coyne speaking at The Amazing Meeting in 2013. Photo by user zooterkin, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sigmund Freud famously described religion as a collective neurosis, stemming from the longing for a father, a fear of death, and a hope for a life after this one.

This presents a decent first go at answering a puzzle familiar to many atheists—how can so many people believe that? But to appeal to such psychological motivations in a debate is pointless at best, condescending and derailing at worst, and shouldn’t be part of our discourse.

As interesting a puzzle as religious belief is to an atheist, it’s worth noting that the psychology of religious belief says nothing about whether or not God actually exists. By itself, it’s no more evidence against God than the phylogenetic development of number cognition is evidence against math, or the neuroscience of moral emotions is evidence against morality.

Purely scientific interests aside, “Why do they believe that?” is only interesting if we’ve already assumed that they’re wrong. Otherwise, there’s nothing to explain.

This way of handling dissenting positions—my view has reasons and your view is something I just need to explain away with psychology—seems like the hallmark of dogmatism and closed-mindedness. They’re just angry at God, or they’re just jealous of our success, or they’re just expressing a longing for their fathers in a form of wish fulfillment, and so on. Tangents like this do nothing but show everyone involved that you’re not arguing in good faith.

Treating others as unwilling subjects of psychoanalysis is toxic to discourse, and it’s something I see many atheists take part in too frequently. The most recent example comes from Jerry Coyne, though it’s hardly limited to him. In a new piece, Coyne asks, “Why are faitheists so nasty?” and writes:

They’re not angry at New Atheists; they’re angry at themselves—for being unable to believe in a God that they know doesn’t exist. And they’re angry at that God for not existing. They just take it out on us.

To start, you can’t chalk anything in psychology up to something so simple as “they’re just angry at themselves and taking it out on us.” Furthermore, Coyne’s thesis is not only completely at odds with my own personal experience—“faitheists” on the whole seem to prioritize a cooperative approach and rarely seem to respond in kind to the personal attacks some “New Atheists” heap on them—but it also goes against the only scientific evidence on the topic that I’ve seen.

A report from scientists at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga put forward research into a preliminary taxonomy of nonbelief. The category that most closely matched “faitheists”—ritual atheists—scored lowest on scales of dogmatism and highest on scales of positive relations with others. Contrast this with antitheists—the category that seems closest to “New Atheists”—who scored highest on measures of narcissism, dogmatism, and anger.

But even if Coyne were right, it’s unclear what this adds to the conversation—other than to get a jab in at another group’s expense. It says nothing about whether Richard Dawkins’ accounts of religious belief are simplistic, or how we ought to engage with religious believers, or whether policing our own is more appropriate than heaping scorn on others.

Similarly, it’d be inappropriate for me to respond to “New Atheist” positions by saying “oh you’re just angry,” or “‘New Atheists’ are just being narcissistic.” Comments like that have nothing to say about whether or not religion is harmful, or what approach atheists should take to working with the religious.

If these discussions are worth having, it’s worth leaving amateur psychoanalysis out of them. And here, we can take a cue from the host of this column, my friend and “faitheist” Chris Stedman:

Bill O’Reilly: “Are [atheists who engage in the so-called ‘War on Christmas’] that bitter against religion? Is that what it is? Did they have a bad experience with organized religion? Is it bitterness?”

Chris Stedman: “I don’t want to psychoanalyze atheist activists who prioritize that.”

The author of this piece is Vlad Chituc. Chituc graduated with distinction from Yale University with a B.S. in Psychology. He now works as a researcher in a behavioral economics lab at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, where he lives with his dog. He is someone you can follow on Twitter.