(Travelblog is an occasional series of posts by RNS Editor-in-Chief Kevin Eckstrom, who’s on the road in Boston, Honolulu, Jakarta and Banda Aceh with the 2014 Senior Journalists Seminar, sponsored by the East-West Center in conjunction with the U.S. State Department)

HONOLULU (RNS) “Are you a Christian?”

It’s a question I’ve been asked several times over the past week as I’ve traveled with a group of U.S. and foreign journalists. By my count, most of the foreign journalists are Muslims, and as they’ve tried to explain the Muslim world to me, I’ve been trying to explain Christian America to them.

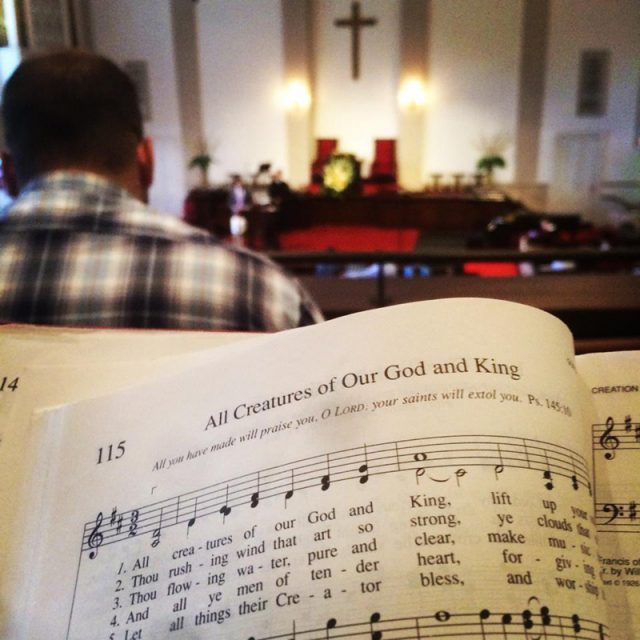

Members of the 2014 Senior Journalists Seminar attended Sunday services at Boston’s Park Street Church. Photo courtesy Jaweed Kaleem / Huffington Post.

More often than not, my new foreign colleagues want to know where I’m coming from.

It’s an innocuous question, and there’s nothing more meant by it than inquiries about basic biography. But in the conversations, I’ve detected a little more — not just “Are you a Christian?”, but sometimes “What kind of Christian are you”?

At first, it caught me off guard. Maybe it shouldn’t — any veteran religion reporter can tell you it’s one of the hazards of this beat. As we probe the spiritual lives of people we interview, sometimes the same questions are directed back at us. There’s no consensus on how to respond — most religion reporters have their own ways of answering (or dodging) the question.

The Religion Newswriters Association offers this guidance:

Say, “I’m Christian” or “I’m Jewish” or “I’m Muslim,” but leave it at that and quickly begin the interview.

Or

Some reporters say, “The most important thing you need to know is that I will listen to you and that I am committed to representing your faith accurately and fairly. This interview is about your faith, not mine.”

But this week has caused me to rethink both the question and the answer.

I’ve answered them honestly — yes, I am a Christian, or to borrow from U2’s Bono, I am a Christian, but probably not a very good one. What I really want to say is “Yes, I’m a Christian, but not like the kind you’ve seen on TV.”

Pressed further, I’ll tell them that I was raised evangelical but am currently settled amongst the Episcopalians. When that word registers a blank stare, I tell them it’s the American branch of the Anglican Church. More blank stares lead to something along the lines of “The Church of England … where Prince William got married.” That usually does the trick.

I was talking with a fellow American reporter on the trip who’s Jewish. After our group attended Sunday services at Boston’s Park Street Church — a proud bastion of conservative evangelicalism is the heart of blue Boston — she asked what I thought of the service. It felt both familiar and foreign, I said. Familiar in the sense that I knew the hymns and what to expect; foreign in the sense that I couldn’t recall that this was ever the air that I once breathed.

I found myself explaining the intricacies of evangelical life to my new friends, but the theological minutiae seemed lost on them. When one of my colleagues asked the difference between Protestants and Catholics, I realized that such theological niceties really didn’t matter to them.

All of which brings me back to that initial question, “Are you a Christian?” and then my “what-kind-of-Christian?” interpretation. It dawned on me that it’s the same question we often ask of Muslims. Not, “Are you a Muslim?” but rather “What kind of Muslim are you?” Are you the kind of Muslim that subjugates women? Are you the kind of Muslim that endorses terrorism? Are you the kind of Muslim that hates America?”

Of course that’s not what we say, but I suspect it’s often what we mean. And just as my new Muslim friends don’t seem to care what kind of Christian I am, maybe it’s time that we stop putting qualifiers on the “Are you a Muslim?” question.

One of my new Muslim friends drinks alcohol, while another is more observant and joined in the Friday prayers we attended at a Washington mosque. Still another doesn’t go to mosque at all. I suppose their words and actions tell me what kind of Muslims they are, and that should be good enough. Where it gets uncomfortable is when the same standard applies to me — I don’t need to tell them I’m X kind of Christian; I suppose it’s just enough for me to show them. And, inshallah, hope that’s good enough.

The tagline of our three-week fellowship is “Bridging Gaps Between the United States and the Muslim World.” For us, that starts with our work as journalists. In order to bridge gaps, you first have to build trust. And trust starts with honesty.

The RNA resources offer this other piece of advice:

“Say what your faith is and where you worship. Some reporters say that they feel they need to be honest and open with sources because they are asking sources to be honest and open with them. It is a way to build trust.”

And all God’s people said Amen.