(RNS) Although immigration created our nation, prejudice and discrimination have always dogged those yearning to breathe free.

(RNS1-OCT04) Christopher Columbus, seen here in “The Landing of Columbus” by John Vanderlyn in the Capitol Rotunda, is best-known as an explorer, but he could also be considered America’s first European “immigrant.” RNS photo courtesy of Architect of the Capitol/Library of Congress.

Christopher Columbus, the first European “immigrant,” represented a repressive Spanish monarchy that expelled its Jews in 1492 and its Muslims between 1609 and 1614. Both events were scrubbed from the heroic Columbus narrative. Instead, we were taught the brave explorer “discovered” America. In reality, he opened the region to immigrant conquistadors who looted, raped and killed for the imperial glory and financial benefit of Spain.

In 1607, English immigrants established Jamestown in what was called the “New World.” It wasn’t “new,” since many diverse tribes already lived here who were inaccurately called “Indians.” Over time, they lost most of their lands, and often their lives.

A dozen years after Jamestown, new immigrants arrived: Africans in chains as human slaves whose white owners treated them as profitable property, an evil system that continued for nearly 250 years.

With a vast continent to develop, America required cheap immigrant labor. In return, newcomers to the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries gained religious and political liberty, public education, individual rights and economic opportunities. That is why millions of Irish, Slavs, Italians, Greeks, Jews and other immigrants wept in joy when they first saw the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor.

But the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” words written by Emma Lazarus, an American Jewish poet, and inscribed on the statue’s pedestal, frequently confronted severe prejudice and discrimination. Asian immigrants, or “the Yellow Peril” as bigots called them, were especially despised.

In 1924, anti-immigrant fever peaked when Congress enacted restrictive legislation that banned Asians from entering the United States and limited immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.

The bill’s co sponsor, U.S. Rep. Albert Johnson, R-Wash., said the law would block “a stream of alien blood, with all its inherited misconceptions … ” from entering America. Sen. David Reed, R-Pa., the other co-sponsor, represented “those of us who are interested in keeping American stock up to the highest standard — that is, the people who were born here.” Southern and Eastern Europeans (many of them Catholics and Jews), he believed, “arrive sick and starving and therefore less capable of contributing to the American economy, and unable to adapt to American culture.”

Stephen Wise, the most prominent rabbi of the era, employed sarcasm to express his opposition:

“ … Were Jesus and his twelve disciples on earth today, they would have to cast lots as to which one of them would have the privilege of coming to the United States under the Johnson-Reed bill quota system.”

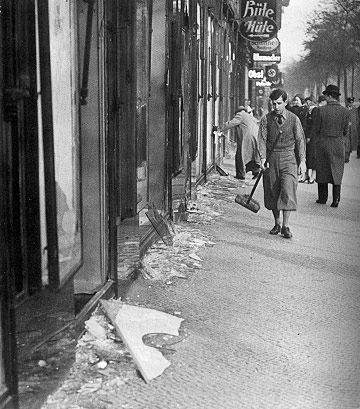

After Kristallnacht’s “Night of Broken Glass” attacks against Jews in 1938, Sen. Robert Wagner, D-N.Y., and Rep. Edith Nourse Rogers, R-Mass., co-sponsored a bill permitting 20,000 German Jewish children, a modest number, to enter the U.S. as nonquota immigrants.

Eleanor Roosevelt unsuccessfully urged her husband, Franklin, the president, to support the bipartisan bill, but anti-Semites and isolationists attacked the legislation along with the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the bill died in committee.

FDR’s cousin Laura Delano Houghteling, whose husband was the U.S. commissioner for immigration and naturalization, opposed the Wagner-Rogers legislation, declaring: “Twenty thousand charming (Jewish) children would all too soon grow into 20,000 ugly adults.”

A year later, State Department official Breckinridge Long was equally clear about blocking the entry of Jewish refugees into America:

“ … We can delay and effectively stop for a temporary period of indefinite length the number of immigrants into the United States. We could do this by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way and to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative devices, which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas.”

By 1940, an upset Eleanor Roosevelt learned of Long’s memo and his bureaucratic plans to block Jewish immigration. She urged her husband to meet with Long and “get this cleared up quickly.” But the First Lady was again unsuccessful.

Long was able to set up “obstacles” for Jews and others who applied for immigrant status. Between 1933 and 1943 there were more than 400,000 unfilled entry visas for people living in Nazi-controlled Europe.

The hatred of current immigrants by the descendants of earlier immigrants remains a well-documented and shameful reality of American history.

YS/MG END RUDIN