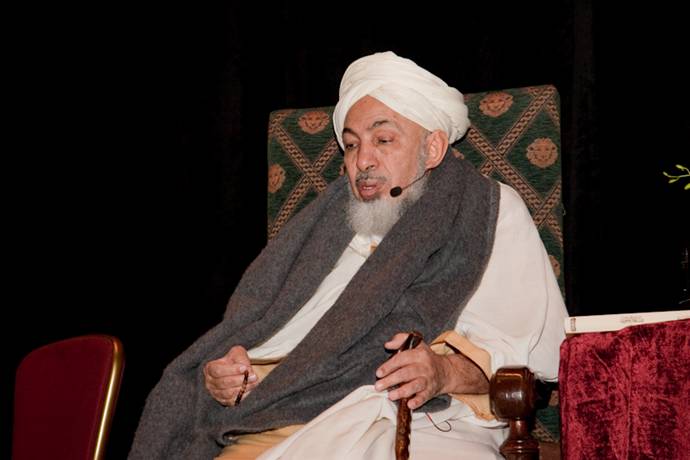

(RNS) In his address to the United Nations on Wednesday (Sept. 24), President Obama singled out one Muslim cleric, Sheikh Abdullah bin Bayyah, for having the courage to issue a fatwa against the Islamic State, or ISIS, or ISIL — or, if you are French, “Daesh.”

Bin Bayyah is a member of the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies in Abu Dhabi, and Friday he and other religious leaders joined a symposium combating radicalism and extremism in Washington, D.C. Which raises a few questions:

What the heck is a fatwa anyway?

A fatwa — an Arabic word — is a legal opinion made by an Islamic judge or cleric about an area of Islamic law. It’s kind of like when the U.S. Supreme Court issues a decision. But that’s where the similarity ends.

Any Islamic cleric can issue a fatwa. But no fatwa is universally binding across Islam. If that were true with the Supreme Court, then only those Americans who agreed with Antonin Scalia — and yes, there are some — would need to worry about the Hobby Lobby ruling, and those who agree with Ruth Bader Ginsburg would go on as if the Hobby Lobby case did not exist.

Fatwas are not issued at random — a case must be brought before a cleric for a fatwa. Fatwas can be issued for very small things — like what to do if you are on a plane and can’t say your required prayers — to very large things — like what do about the Islamic State. Such petitions can be sought by individual Muslims or by Muslim communities.

So, if fatwas are not binding, then why do Muslims pay attention to them?

Because fatwas are based on a cleric’s reading of Islamic scripture and other revered texts, and because scripture bears weight with religious people. They are considered informed legal rulings, not random opinions or ideas. Generally, Muslims follow only the fatwas issued by clerics in their particular branch of Islam — Sunni Muslims heed fatwas issued by Sunni clerics, Shia Muslims adhere to fatwas issued by Shia clerics, etc. Think how while Protestants like what Pope Francis says about the Bible, they are not bound by it even though both Catholics and Protestants are Christians.

But don’t underestimate the power of a fatwa just because it isn’t binding. Just ask Salman Rushdie. His 1988 book, “The Satanic Verses,” upset a bunch of Muslims who felt it disparaged the Prophet Muhammad — a serious offense within Islam. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then chief cleric of Iran, issued a fatwa that called for Rushdie’s head. (In 1998, Iranian President Mohammad Khatami said Iran no longer supported Rushdie’s murder.) A slew of other Muslim clerics, in turn, issued fatwas saying Khomeini’s fatwa was invalid. Still, Rushdie, his wife and son spent years hiding and in fear for their lives, something he recounts in the memoir “Joseph Anton.”

Well, I definitely don’t like the sound of that fatwa. Can I get another one?

Yes! Muslims can go to as many clerics as they like and ask for a fatwa about anything until they get a ruling they like.

So, if fatwas are not binding and can be issued by clerics of different leanings, what is the big deal with bin Bayyah’s fatwa?

The big deal is that very few Muslim clerics have issued critical fatwas about the Islamic State, and Western leaders see attaining Muslim allies like bin Bayyah and others as critical to defeating radical Islam. In his fatwa, bin Bayyah wrote: “The means to evil ends are also evil, and noble ends can be reached only by noble means. So one cannot use genocide, murder, oppression, or vengeance to establish truth and justice.”