Vatican City — Prelates and religious dignitaries from around the world fill St. Peter’s Basilica as a concelebrated Mass opens the Second Vatican Council on Oct. 11, 1962.

(RNS) Shortly before his death in 1904, Theodor Herzl had an audience with Pope Pius X, hoping to enlist Vatican support for Zionism, the reestablishment of the Jewish people’s independence in its ancestral homeland.

Herzl records in his diaries that Pius told him he could not recognize the Jewish people as such because “the Jews have not recognized our Lord.” “We cannot prevent the Jews from going to Jerusalem,” the pope said, “but we could never sanction it. If you come to Palestine and settle your people there, our churches and priests will be ready to baptize all of you.”

Pius wasn’t particularly hostile towards Jews. He was simply expressing the normative Christian approach down the ages that the expulsion of the Jews from their land was proof of divine rejection. The church, according to this view, was the new and true Israel, having replaced the old one — the Jewish people.

Moreover, as the church father Origen declared, “the blood of Jesus falls on Jews not only then, but on all generations until the end of the world.”

This deicide charge was used to justify persecution of Jews for centuries, culminating in the terrible Holocaust. Indeed, the Protestant chaplain of the Nazi S.S., at his trial in 1958, declared that the Holocaust was the “fulfillment of the self-condemnation which the Jews brought upon themselves before the tribunal of Pontius Pilate.”

While Nazi ideology was secular and pagan, the “Final Solution” regarding the Jews was mostly implemented by baptized Christians in ostensibly Christian lands. Its implications and ramifications for Christianity were therefore profound.

There were, however, notable Christian heroes who stood out as exceptions. One was Angelo Roncalli, the papal envoy in Turkey and one of the earliest Western religious figures to receive information on the Nazi murder machine. He helped save thousands of Jews from their would-be killers and was deeply moved by the plight of the Jewish people. In 1958, Roncalli was elected Pope John XXIII.

(RNS) Pope John XXIII is carried on a papal throne to the opening session of the Second Vatican Council in 1962. Religion News Service file photo.

Soon thereafter, he announced his intention to convene the Second Vatican Council to “update” the church and address critical issues. Many Jews and Christians saw this as a unique opportunity for the church to review its teaching regarding Jews and Judaism. Jewish organizations, the American Jewish Committee in particular, joined to advance this cause.

Although John XXIII did not live to see it, almost exactly 50 years ago, the council’s “Declaration on the Relation of the Church to non-Christian Religions” — popularly known as “Nostra Aetate” — was released. Section 4, dealing with the relationship with the Jewish people, admonishes against portraying the Jews as rejected by God and as collectively guilty for the death of Jesus at the time, let alone in perpetuity.

It furthermore affirms the unbroken and eternal covenant between God and the Jewish people, eliminating in one stroke, as it were, any theological objections to the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland and to sovereignty within it. The document categorically condemns anti-Semitism and calls for “fraternal dialogue and biblical studies” between Christians and Jews.

It took an additional 28 years for full diplomatic relations to be established between the Holy See and Israel, due more to politics than religion. In the meantime, Pope John Paul II had visited Rome’s central synagogue, where he referred to the Jewish people as Christians’ “dearly beloved elder brother,” and he described anti-Semitism as “a sin against God and man.” In 2000 he made his “jubilee” visit to the Holy Land, where he paid his respects to Israel’s highest elected officials.

(It’s worth noting that both John XXIII and John Paul II are now official Catholic saints.)

Since “Nostra Aetate,” Catholic-Jewish relations have flourished. Indeed, there may be nothing in human history that quite parallels such an amazing transformation. A wondrous achievement in itself, the revolution in Catholic-Jewish relations also suggests something more universal about relationships between religious communities.

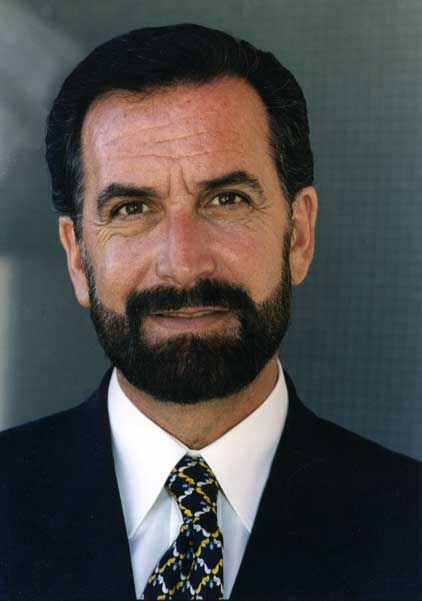

Rabbi David Rosen, the international director of interreligious affairs for the American Jewish Committee, is the Jewish member of the board of directors for the King Abdullah Center for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue.

If one religion can go from seeing another as contemptible and condemnable, to one that is respected and beloved, it can surely serve as a model for humanity at large, declaring that no chronic neuralgic relationship is beyond transformation.

Jewish-Muslim relations today are a case in point. While they are inevitably affected by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, recall, however, that Islam had never denigrated Judaism in the way that Christianity had. We do not have to wait for a resolution of Middle East conflicts.

Everywhere, religious communities can overcome negative images of the other through positive engagement, purify themselves of prejudice, and contribute to the well-being of society at large.

(Rabbi David Rosen is the American Jewish Committee’s international director of interreligious affairs. He was a member of the team that negotiated the establishment of full relations between Israel and the Holy See.)