Crusaders bombard Nicaea with heads in 1097.

(RNS) The pieces of the religious puzzle that make up the USA Network’s biblical conspiracy action series “Dig” are beginning to fall into place, and the picture they are revealing is one of history — highlighted by a colorful streak of fiction.

Here be spoilers! Read on only if you are up-to-date with the 10-part series, or want to ruin it for yourself and others.

“Order of Moriah”

This secret religious order, supposedly dating from the Crusades, seems to be a product of the “Dig” writers’ imaginations. But, like many of the show’s fictional aspects, it is based on historical fact.

The Crusades, which mainly took place from 1095 to 1291, were an attempt by the Rome-based Catholic Church to retake the Holy Land — Jerusalem and its environs — away from its Muslim rulers.

During that time, the church founded several monastic religious orders whose members traveled to Jerusalem. Some fought with the armies; some cared for the wounded and sick. The most famous of these orders were the Knights Hospitallers, the Knights Teutonic and the Knights Templar.

It is perhaps the Templars that the Order of Moriah is based on. Officially named “The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon,” the Knights Templar were anything but poor. They owned land from Rome to Jerusalem and were involved in finance throughout the Christian world. They loaned money to King Philip IV of France and the church.

That’s where they got into trouble. When the king didn’t want to pay them back, he pressured Pope Clement V to disband the knights. The resistant knights were charged with heresy and many members were arrested, tortured and burned at the stake. Legend holds that some members went into hiding — and took a lot of loot with them.

Writers have been making fictional hay with the Knights Templar and other so-called “secret” religious orders since Sir Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe” in 1820. The most famous example is Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code,” in which a Templar-like order called the “Priory of Sion” keeps a really, really big secret about the nature of the “Holy Grail.”

Enter “Dig,” whose evil archaeologist, Ian Margove (Richard E. Grant), is after the “treasure” the Order of Moriah is supposed to have buried somewhere in Jerusalem.

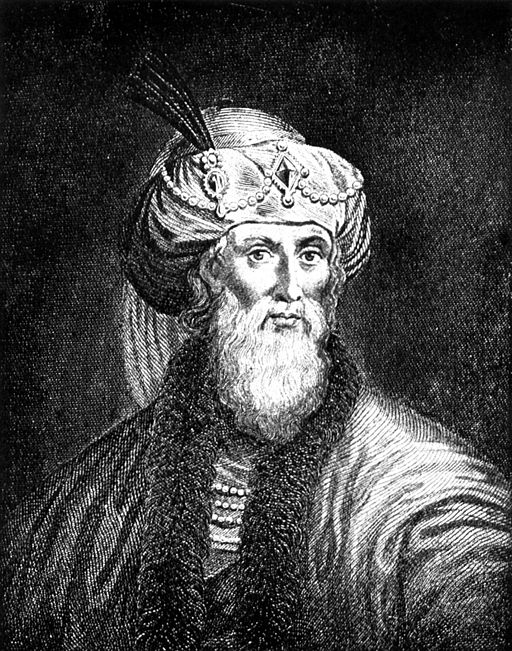

The romanticized woodcut engraving of Flavius Josephus appearing in William Whiston’s translation of his works.

Flavius Josephus

Archaeologist Margrove says that “according to Flavius Josephus,” the breastplate will pinpoint the location of the treasure.

Flavius Josephus was a first-century Jewish historian. Contemporary Jews are most familiar with him for his firsthand account of the revolt of the Maccabees, a Jewish sect that rose against Roman rule, while Christians know him for his description of Jesus’ early followers.

But Josephus’ own biography is as fascinating as his historical works. He was born to well-to-do and noble Jews in 37 C.E. in Jerusalem. At 16, he went to live with a desert hermit — perhaps an Essene — but returned to Jerusalem at age 19 and joined the Pharisees, a Jewish priestly sect. During the First Jewish-Roman War, he was in charge of a section of Jerusalem’s forces.

At one point, Josephus and 40 of his followers were trapped in a cave. Rather than surrender, Josephus persuaded them to commit group suicide, with each man drawing lots and killing a companion, so no one would have to kill himself. For whatever reason — an act of luck or the hand of God — by the time the lots got around to Josephus, he and another soldier were the last ones standing. And they surrendered to the Romans. Josephus went on to become a friend of the Emperor Vespasian and the recipient of a Roman pension.

For this reason, many have considered him a traitor — he’s been called the “Jewish Benedict Arnold” by some scholars. But in the past few decades, some scholars are rehabilitating his image, claiming he joined the Romans out of a sense of deference or even unwillingly.

Whatever the truth, the characters of “Dig” are right to turn to Josephus for information about early Jewish rituals and practices. His book “Antiquities of the Jews” describes first-century Jewish religious garments and ritual items, including a priest’s breastplate that is critical to the “Dig” plotline.

But using such a breastplate as a treasure map is fictional — not historical — at all.

YS/MG END WINSTON