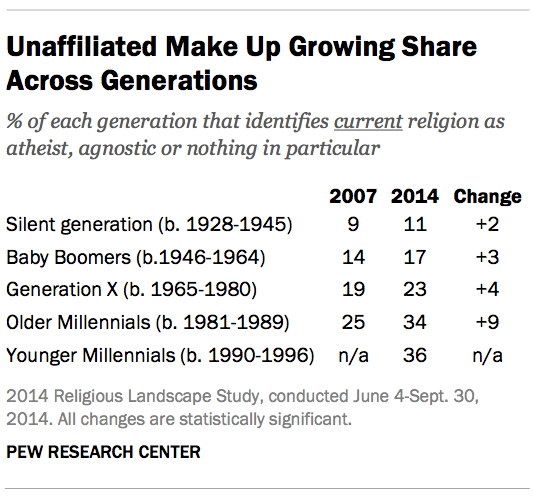

The unaffiliated make up a growing share across generations. Photo courtesy of Pew Research Center

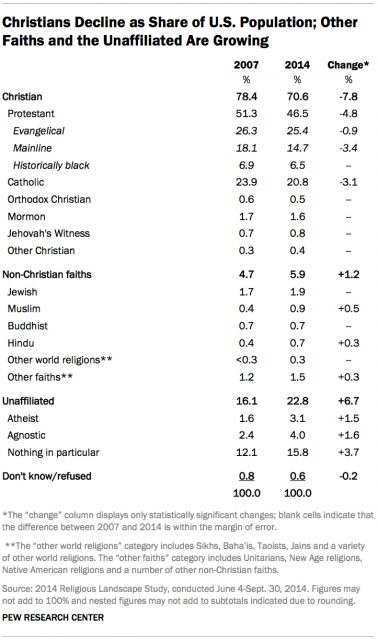

(RNS) The survey of America’s religious landscape released by the Pew Research Center last week engendered controversy, with headlines and articles latching onto one aspect of the data (usually the number of self-identifying Christians dropping to 70 percent) and then speeding away to exaggerated conclusions.

What’s the story here? Is it the “demise” of Christianity? Or the steadiness of religious practice? Is it the accelerating decline of denominational affiliation? Or the slow but upward tick of “evangelicals”?

Like so many surveys, there are different ways one can interpret the data.

Evangelical leaders saw the statistics as vindication: The number of evangelicals has grown, a sign that “true Christianity” is winning the day over the “progressive” mainline denominations or a cultural “Christianity-in-name-only.”

Liberal Christians pushed back against evangelical “triumphalism,” pointing out that some of the worrisome statistics that were once true only of mainline Protestantism are now showing up in evangelical denominations as well.

These divergent perspectives on the Pew survey are connected to larger narratives that frame how conservative and liberal Christians in the United States see themselves. In “The Righteous Mind,” Jonathan Haidt describes the different “stories” that arise, depending on whether you lean to the left or right politically. Though he has written primarily about “liberals” and “conservatives” from a political standpoint, I find his analysis easily applies to “liberals” and “conservatives” within Christianity also.

Haidt describes the liberal narrative as “heroic liberation.” Applied to the church, liberals would say the authoritative and hierarchical structures of the church (not to mention the way the church has wielded power in the past) are elements of tradition that keep people in chains. Liberals want to set people free from outdated or misunderstood dogma.

Haidt summarizes the conservative narrative as the “heroism of defense.” Applied to the church, conservatives are protecting their heritage, much like a home that needs to be reclaimed after significant damage has been done by termites. Loyalty to the church is declining because submission to God’s word is being subverted. Conservatives want to hold tightly to the life-giving truths of Christianity and maintain the church’s distinctiveness, no matter how unpopular it may be.

If you’re examining the Pew survey from the “liberation” narrative, then the solution is for the church to “get with the times.” To wit: If only churches would stop taking backward and damaging social positions, maybe they’d start growing again!

Christians decline as a share of the U.S. population; other faiths and the unaffiliated are growing. Photo courtesy of Pew Research Center

If you’re looking at it from the “defense” narrative, then the solution is for the church to “hold the line” and clarify true Christianity from its counterfeits: If only the “cultural” Christians would disappear altogether, then we’d know who really believes in traditional Christianity!

Which one of these interpretations is right? I’m one of the convictional Christians: “traditional” not progressive, “conservative” not liberal. Not surprisingly, the “heroism of defense” resonates more with me than “liberation” does. Still, I find elements of both these interpretations shortsighted.

Regarding the progressive interpretation, I don’t think it’s accurate for commentators to interpret Christianity’s decline as a backlash against evangelicalism’s unpopular stances on morality and sexual ethics. According to this thesis, we ought to see an uptick in mainline denominations that hold to liberal views. Instead, mainline Protestantism continues to hemorrhage members, especially millennials.

Furthermore, those who still identify as Christians are becoming “evangelicalized” (a term from researcher Ed Stetzer); that is, what remains of American Christianity is increasingly evangelical in its outlook.

Regarding the conservative interpretation, it’s shortsighted for evangelical leaders to celebrate a declining number of self-identifying Christians, as if the fading of cultural Christianity is, in and of itself, a good thing.

I’m glad to see Christianity become more convictional, not just cultural. But the Pew survey shows “nominal” Christians now choosing “none of the above,” which indicates that the consciousness of the wider culture is moving away from religious devotion. Evangelicals can celebrate the steadiness of our own religious fervor, but the fact that our friends and neighbors are choosing “none” means they will probably be harder to reach moving forward.

Trevin Wax is managing editor of The Gospel Project and author of multiple books, including “Clear Winter Nights: A Journey into Truth, Doubt and What Comes After.” Photo courtesy of LifeWay Media

In the end, if you are an evangelical, the Pew survey offers reason for celebration and cause for concern. You can celebrate that even as fewer people now self-identify as Christian, more Christians identify with the evangelical movement. But we ought to be concerned about the growing apathy and indifference among Americans toward religion in general.

Evangelicals may be shaping Christianity like never before, but Christianity is no longer shaping American culture like it once did. And there’s our challenge: While liberal and conservative Christians passionately debate the data, more of our neighbors checking “none” say, “Who cares?”

(Trevin Wax is managing editor of The Gospel Project and author of multiple books, including “Clear Winter Nights: A Journey Into Truth, Doubt and What Comes After.”)

YS/MG END WAX