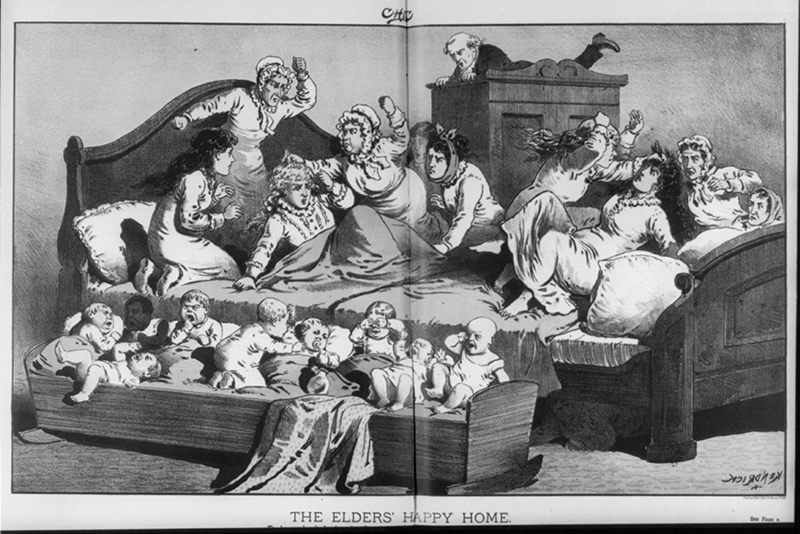

“The Elders’ Happy Home” cartoon from 1881. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

PROVO, Utah – Far from the rosy glow of true love depicted in today’s romantic comedies and religious sermons, marriage in earlier times was more often akin to slavery for women — with husbands as the master.

By the 19th century, however, some women wanted more love and less abuse, and so, with few legal options, wives began to flee from these matches, including from Mormon polygamous unions and American monogamous coupling.

‘‘Some people — and perhaps quite a few women — chose plural marriage over what they saw on the other side,” historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich told a crowd of Mormon scholars recently.

“Some women ran away from polygamy — one of my own great-grandmothers did — but it is interesting to contemplate that some women also ran away in order to join it.”

A Harvard professor and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Ulrich knows that conclusion runs counter to the belief that LDS “plural marriage,” as it was known, was a “patriarchal backwater against the backdrop of nuclear marriage that was emerging in [that] century.”

But she does not “find that interpretation persuasive.”

Ulrich, president of the Mormon History Association, gave the concluding address — titled “Runaway Wives, 1840-1860” — at the group’s 50th anniversary conference in Provo.

Like a master seamstress, the Boston-based scholar gently drew out a thread about marital issues she had discovered during eight years of research for her forthcoming book, “A House Full of Females: Mormon Diaries, 1835-1870,” to be published by Alfred A. Knopf in the next year.

Ulrich began her speech by describing a pivotal work of 18th-century literature, Samuel Richardson’s 1748 novel, “Clarissa.” In it, Clarissa forsakes the marriage arranged by her parents and runs off with a seductive soldier, winding up in a brothel and ultimately dying.

Later, American Revolutionary and future U.S. President John Adams famously declared, “The people are Clarissa.”

The notion of leaving a planned marriage, Ulrich said, became so worrisome that British and American lawmakers debated what caused it and how to manage it, especially as cultural norms were shifting.

“If the foundation of society is not based on hierarchical and powerful authority, it is going to rest on the decision-making of rational people,” such male legislators reasoned.

“But can women be rational?” they asked, according to Ulrich. “Without the authority of the father, is a woman going to succumb to the seducer?”

No debate, or legislation for that matter, kept wives — and would-be brides — from abandoning untenable situations. That’s because legal divorce literally was not possible (unless a woman had financial means or connections).

“If she was wed for life to a hostile or abusive man or even one who refused to let her worship as she chose — unlike slaves, wives ostensibly chose their own masters but what if they chose unwisely?” Ulrich asked. “They were stuck.”

The term “family” comes from “famulus,” which originally meant “slaves,” and then came to suggest a man’s household, including slaves, servants and dependents, even wives and children.

“If a wife left her husband, he could actually claim property damages, since her labor and presence were his property,” the historian recounted. “He was allowed to exercise mild correction as a parent might to a child in order to maintain authority.”

Such were the matrimonial conditions at Mormonism’s 1830 birth in upstate New York, and they continued to be a problem as the Latter-day Saints gathered in Kirtland, Ohio.

The first marriage LDS founder Joseph Smith performed in Ohio was for Lydia and early Mormon leader Newel Knight, Ulrich said. She had left her alcoholic first husband and fled to Canada before meeting the Latter-day Saints and joining the church.

“About 20 percent of plural wives in Nauvoo (Illinois) before Joseph Smith’s death were legally married to other men,” she said. “Their splits were either consensual or the wives left through folk divorces or desertions, sometimes by the husband.”

Smith began to unite couples “in an idealized notion both spiritual and sentimental,” she said. “Relationships are too important not to marry where there is affection. You don’t want to be bound for eternity with someone you can’t get along with.”

American suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited the Beehive State in 1871 and didn’t see any difference between monogamy and polygamy.

“The condition of women has been the same in all ages and latitudes … under Protestantism, Catholicism and Mormonism, women are divinely ordained subjects of men,” the historian quoted Stanton as saying. “Brigham Young (Smith’s successor) showed a deep understanding of human nature in teaching women to be subservient on Earth in order to get a reward in heaven, but he was no different than leaders of any other religions.”

The new faith’s openness on some issues was different, Ulrich said. In Utah, for example, a divorce was relatively easy to obtain, unlike the stringent conditions imposed elsewhere in the nation.

The fourth LDS Church president, Wilford Woodruff, who would eventually pronounce the so-called Manifesto to end polygamy, once married Mary Webster as a plural wife. The union lasted a few weeks because Webster died. In the notices of her death, she was described as a “widow,” but she was not a widow. She left her husband, also a Mormon, in Massachusetts but who refused to migrate to the West.

“Latter-day Saints shockingly were closer to the so-called free lovers of the 19th century,” Ulrich said, “than to the evangelical Protestants who were opposing them (Mormons) and opposing divorce.”

Mormons idealized marriage. They made it a sacrament, she said, “but they were far too comfortable with divorce and welcoming runaway wives into the fold to belong in that conservative camp.”

Kristine Haglund, editor of “Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought,” was impressed by the reach and depth of the historian’s research on runaway wives.

Ulrich’s research “didn’t make the idea of polygamy any more appealing,” Haglund said. “It just made 19th-century marriage seem pretty horrifying all the way ’round.”

But her speech, Haglund wrote in an email, “showed that the past is both more and less like the present than we usually think.”

Clearly, she said, there is “no golden age we can look to as a moment when ‘traditional’ marriage was a universal norm.”

(Peggy Fletcher Stack writes for The Salt Lake Tribune.)