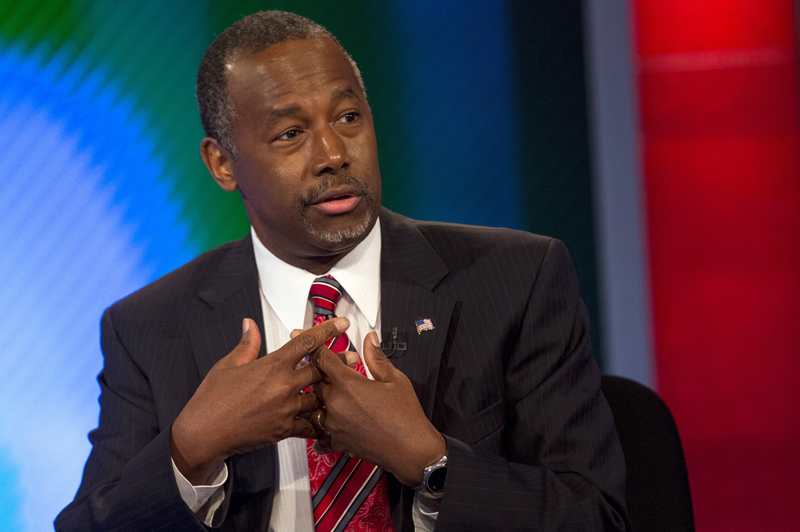

Republican presidential candidate Dr. Ben Carson appears on Fox Business Network’s “Varney & Co.” in New York on Aug. 12, 2015. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Brendan McDermid *Editors: This photo may only be republished with RNS-GRIFFITH-COLUMN, originally transmitted on Sept. 23, 2015.

(RNS) When Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson stated that he does not believe a Muslim belongs in the White House, he was following a long-standing, bipartisan American political tradition of assailing religious minorities for their perceived anti-Americanism.

Take anti-Catholicism, for example.

Former President John Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1821 that “A free government and the Roman Catholic religion can never exist together in any nation or country,” a sentiment shared by 20th-century American Protestants worried that the Vatican might be mobilizing the likes of Al Smith and John F. Kennedy as papist Manchurian candidates.

More recently, there were attacks on Mitt Romney’s Mormon faith from both left and right.

Muslim advocacy groups and Democratic and Republican personalities alike were quick to denounce Carson for his comments’ insensitivity. And he walked back his comments in a Facebook post where he acknowledged “peaceful Muslims” but insisted that only Muslims who renounced Shariah could be considered for the presidency.

But the critics might have intensified their critiques with reference to the history of Carson’s own religious tradition.

READ: Will evangelicals welcome Pope Francis? The good news depends on it

Carson is a Seventh-day Adventist, a Christian denomination with roots in antebellum millennial prophecy and late 19th-century health reforms.

Adventists are also known for their Sabbath observance on Saturdays.

It is the history of public controversy around this hallmark doctrine that makes Carson’s statements about Muslims and the presidency so interesting, because Adventists once occupied a similar status as a distrusted religious minority in American life.

Saturday worship meant Adventists sometimes were on the wrong end of 19th-century reform measures. As part of a broader mainstream Protestant push to secure America’s “Christian nation” status, reformers known as Sabbatarians pushed for legal recognition of Sundays as days of rest, in keeping with the Ten Commandments.

Sabbatarianism was an attempt to resist increasing secularization in society and thwart the perceived un-American threat of immigrants’ religion (mainly Catholicism). But it also was a problem for the Adventists, who took their Sabbath rest a day earlier and had no qualms with business as usual on Sundays. As a result, some Adventists were fined and prosecuted for breaking “blue laws.” Historian Richard W. Schwarz has documented over 100 such arrests of Adventists from 1885-1896.

Adventist victimization under blue laws helped make separation of church and state a top lobbying priority of the denomination. As Malcolm Bull and Keith Lockhart have shown, Adventists helped organize successful campaigns against a congressionally mandated national day of rest in 1889 and 1926, and against similar state efforts in the 1950s and ’60s.

In the late 1940s, they joined other Protestants to found American United for Separation of Church and State, a group best known today as a thorn in the side of religious conservatives (though Adventists left Americans United in the mid-1990s).

READ: 3 reasons Jews should recommit to Judaism 50 years after Sandy Koufax

Carson is certainly capable of championing religious liberty. However, his statements to that effect have tended to echo Republican talking points about Christians being under attack for their beliefs on homosexuality. His remarks also suggest that he believes, as many Americans do, that Muslims themselves are a threat to religious freedom. According to Carson, because Muslims “feel that their religion is very much a part of your public life” and because Islam “encourages you to lie to achieve your goals,” American Muslim politicians could likely not be trusted.

There are always challenges in assessing the relationship of a candidate’s faith to his or her politics. Americans now have no problem with Catholics running for presidential office (indeed, more are currently running than at any time in history). But the public would still likely give pause, as midcentury evangelicals suggested, if a pacifist Mennonite were nominated for secretary of defense.

One wonders whether Carson’s rhetoric about Muslims would at all be tempered if he recalled the example of beleaguered Adventists staring down forced Sabbath-keeping.

Attention to his own tradition’s history, as well as the very real challenges that religious minorities such as Muslims in America face today, unfortunately might not play well with some of the voters that Carson, Donald Trump and other nonestablishment presidential campaigns appeal to.

However unorthodox it may be, Trump’s minimalist “little wine, little cracker” faith has the advantage of allowing him to check the Christian box without interfering with whatever his constituency wants to hear about minorities in America, whether Muslim or Mexican.

Aaron Griffith is a doctoral student in American Christianity at Duke Divinity School. Photo courtesy of Aaron Griffith

It is no secret that religious faith is much more important for Carson’s campaign than Trump’s. Remembering the Adventist experience in American life could point Carson’s campaign in a different direction. This may mean the loss of support from voters who would love to see him deepen his anti-Muslim rhetoric. But it might be worth it, if only eternally speaking.

As official Adventist documents state, protecting religious minorities may result in “personal and corporate loss.” But, “This is the price we must be willing to pay in order to follow our Savior who consistently spoke for the disfavored and dispossessed.”

(Aaron Griffith is a doctoral student in American Christianity at Duke Divinity School. Reach him on Twitter @AaronLGriffith.)

YS/MG END GRIFFITH