It could have been worse. Among the conservative Catholic scribbling class, that’s the consensus on the bishops’ synod that wrapped up its business in Rome last weekend. After all, the Final Report made no explicit mention of a path to communion for the divorced and remarried, much less sanctioning “artificial” contraception or living out of wedlock. Same-sex relationships got a peremptory thumbs down.

But the sequel has them scared. Pope Francis took the tiny opening that last year’s synod gave to annulment reform and pushed through new canon law. Who knows what he’ll do with the openings he’s been given now?

“What would be uncharted territory,” writes the New York Times‘ Ross Douthat, “is if this pope decides to act on his irritation with conservatives and/or his vision of decentralization, and use his post-synodal exhortation to make the crack that liberals see already wider, undeniable, visible to everyone.”

“The Final Report is a tolerable text, especially for something produced by a committee of 270,” writes the Catholic Thing’s Robert Royal. “If it had been passed under the papacy of John Paul II, it would have raised little, if any, alarm. But in a context of mutual suspicion and anger, what is tolerable may become intolerable.”

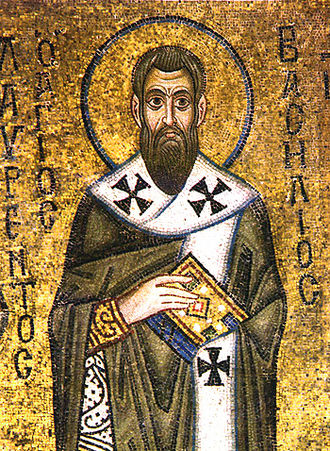

As is usual at moments of impending institutional change, the casus belli acquires a symbolic importance far beyond its specific effect. That’s the case with communion for the divorced and remarried, which reformers wish to permit by drawing on the patristic principle of economia. Advanced by the fourth-century Cappadocian Fathers Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus, economia constitutes a recognition that living in this world sometime makes it impossible to follow the ideal spiritual path.

Understanding that valid marriages sometimes have to be ended by divorce, Eastern Orthodoxy permits sacramental remarriages; however, these have to be conducted in a less celebratory way than first marriages — indeed, penitentially. Such a violation of the principle of the indissolubility of marriage is considered intolerably lax by Roman Catholic conservatives. But in disdaining this mote in the Orthodox eye, they fail to see the beam in their own.

The Orthodox hew to the ideal of the indissolubility of marriage by requiring widows and widowers to take a penitential path to remarriage. Yes, the death of a spouse is generally unavoidable. Nevertheless, second and third marriages, albeit licit, do violate the principle of sacramental marriage as a one-time thing that effects a permanent change in the person.

By contrast, the indissolubility of marriage for Catholics is just “till death do us part.” Then it can be on to the next marriage, and the next one, so long as the present spouse predeceases us.

While I’ve got no dog in this fight, the Orthodox view makes more sense to me. Given the metaphysics of sacramental marriage, how can the Catholics be so blithe about the remarriages of widows and widowers? It must be because it never occurs to them that there’s a problem. It’s always been that way.