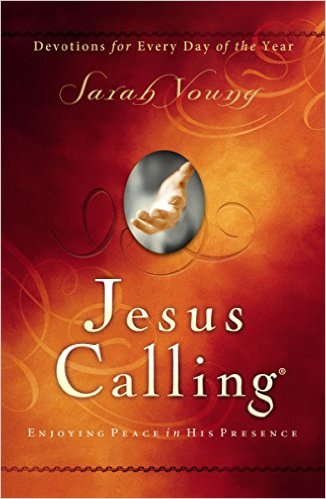

Cover of “Jesus Calling” | Image via amazon.com (http://www.amazon.com/Jesus-Calling-Enjoying-Peace-Presence-ebook/dp/B003IYI7I2)

Jesus Calling never should have been a best seller. The small daily devotional book put out by Christian publishing house Thomas Nelson in 2004 had an unknown author, a cheesy premise, and the bad luck of entering a very saturated market–hundreds of devotional books are published every year, and very few go on to sell like hotcakes.

This one did. Jesus Calling (subtitled “Enjoying Peace in His Presence”) has sold over 15 million copies since its publication. It has spawned an enormous line of spinoff products, from kids’ devotionals to journals to an app you can buy for $9.99. You can even sign up to be a Jesus Calling ambassador if you loved the book and want to promote it “to people in [your] community, church, and online through social media.” Silly, yes. But is it harmful?

That’s what some Christian leaders have been arguing. In the introduction, Young lays out the book’s format: “I decided to listen to God with pen in hand, writing down whatever I believed He was saying.” Many Christians observe a daily devotional time and make these kinds of notes in their journals, writing what they hear God say to them either in prayer of through the Scripture. The book, then, reads like a daily invitation from Jesus to ponder something new: “Come to Me with a teachable spirit, eager to be changed,” we read on January 1st. “A close walk with Me is a life of continual newness.” (Young is at least traditional in her capitalization of pronouns referring to God.)

An author using her voice as a stand-in for God’s is troubling to a number of Christian leaders. Last year, the bloggers at Sola Sisters, a website founded to “sound a warning to today’s church” about New Age-adjacent beliefs, wrote “what is being described by Sarah Young is an extremely occultic practice” and called it “divination.” Self-described “former New-Ager” Warren B. Smith wrote a book called ‘Another Jesus’ Calling in which he set out to reveal the unorthodox practices behind Young’s book. In her 2014 piece on the controversy that erupted over Jesus Calling, Ruth Graham noted that even the publishing house was on the hook: the introduction has been altered, and “Thomas Nelson refers to the book as ‘Sarah’s prayer journal,’ emphasizing that Young is not claiming to speaking for Jesus.”

But it was blogger and pastor Tim Challies who has had the largest axe to grind with Young. He has written several posts about the book–a 2011 review, a take on her children’s version of the book later that year, and a 2014 critique after Graham’s piece was published. Then, yesterday, he published a post outlining 10 Serious Problems with Jesus Calling. The problems weren’t anything new–she claims to speak for God, the book has undergone revision, her practices are occultic, etc–and neither was his conclusion, which was a sweeping condemnation of the book as “dangerous” and “leading people away from God’s means of grace.”

This is where Challies and I diverge. While I can see why some people would dislike and critique the book for its unique voice, and while I don’t personally like the book, I think it’s a net positive that the book exists and has been a tool through which many people have gotten closer to God. Should we be careful about what we read? I’m not convinced. I tend to side with my friend Karen Swallow Prior when she says “books should be promiscuously read.” (This does not reflect her position on this book, which I do not know.) Theology policing is a job best left to the Holy Spirit, and then to people who we know. (It’s also unfortunate that much theology policing comes from men in positions of power and is directed toward women, creating a powerful gender dynamic that does more harm than good in the church.)

There is a difference between criticizing a book and calling it “dangerous,” and I think criticism ought to be fair game. But once we call something “dangerous,” we are precluding it from offering any good, and we are saying that our interpretation–our particular slice of Christianity–is the “right” one.

I was talking with a friend of mine recently and he brought up the gospel passage (in Matthew 16 or Mark 8) in which Jesus asks his disciples, “Who do people say I am?” The disciples gave Jesus a list of names: Elijah, John the Baptist, a prophet. “Who do you say I am?” Jesus asked. At this point, the disciples had been with Jesus for quite a while. They weren’t new to Him, and they knew Him well. Yet until that moment, Jesus had never asked them who He was. There was no theological policing going on–the discipled loved Jesus and knew Him, and they didn’t have to have exactly the right ideas about Him to follow Him.

Jesus Calling has its problems, to be sure, but to my mind those are much more about the spate of products made out of a cash cow for a publisher than whether its author’s theology aligns perfectly with the Reformed Church as interpreted by a handful of bloggers. If the book is dangerous to some readers, let them come to that conclusion on their own. And in the meantime, Jesus is calling.