(RNS) Around 8 million people were forcibly displaced from their homes by violence or other social upheaval in 2015, the largest number ever recorded in a single year, according to the U.N.

While Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon calls the global refugee crisis the “worst humanitarian catastrophe” since World War II, governments and aid groups have been debating what can — and should — be done about the crisis.

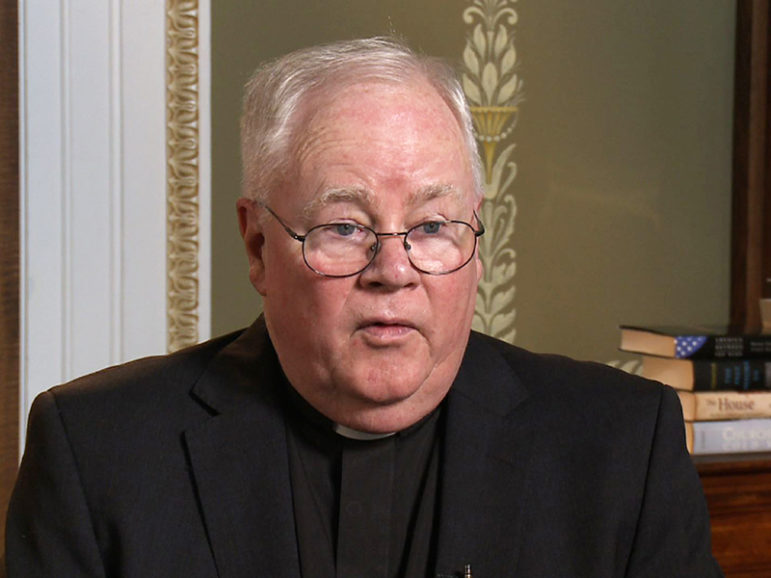

Roman Catholic theologian and ethicist Rev. David Hollenbach, who directs the Center for Human Rights and International Justice at Boston College, spent last fall studying the issue after he was named the 2015 Cary and Ann Maguire Chair in Ethics and American History at the Library of Congress’ John W. Kluge Center in Washington, D.C.

Hollenbach argues that the United States and other developed nations have a moral obligation to find solutions. He spoke about those responsibilities on the PBS television program “Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly.” The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do you characterize the scale of the global refugee crisis?

A: I’m calling it humanity in crisis. There are currently more than 60 million displaced people in the world. This is the largest number since World War II. They are people with no home, no place to live, no citizenship and essentially no way to protect themselves against ongoing problems of human rights violations.

Roman Catholic theologian and ethicist Rev. David Hollenbach directs the Center for Human Rights and International Justice at Boston College. Photo courtesy of Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly

Q: While many news stories focus on migrants trying to enter Europe, aren’t the majority of refugees actually in developing countries?

A: That’s for sure. Of those countries that host refugees coming in, the majority of those people, more than half, are in underdeveloped countries. Countries like Lebanon or Kenya for example, or Chad, or places bordering the Central African Republic. Countries where there is no strong economic development at all are being asked to host huge numbers of refugees. So the issue is, how can we find a way to assist those very poor countries? We’re in a position to be able to do something about that, and therefore, my argument would be that we have a duty to do so.

Q: Why is it a “duty?” Why do you believe we as Americans have ethical obligations here?

A: One, there’s a severe need. Secondly, we have the capability to do something about it. If you can’t swim, you’re not obligated to jump in the river to save a drowning child and cause another death to occur on top of it. But if you’re a good swimmer, you’ve got an obligation to jump in and help that kid who’s in danger of drowning.

Also, we are aware of the crisis. We are not next door to Syria or South Sudan or Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, but we have enough awareness of what’s going on so that I would argue we have “moral proximity” to those needs. And then, we can do so without disproportionate burdens on ourselves. We have resources.

Q: Especially with the Middle East refugee crisis, some people blame the United States and say we bear some responsibility because of our actions in Iraq. Do you think that’s fair? Do you think the U.S. has certain moral obligations because of the actions we’ve taken in that part of the world?

A: I do. We didn’t cause the massive refugee crisis from Syria in any direct way. The causes are the Syrian government, ISIS, and some of the Syrian rebels that are doing all kinds of horrible things. But our intervention in Iraq was the beginning of the set of circumstances that led to the unweaving of the fabric of society in that region. Therefore, I would say that though we are not the cause of this displacement, our intervention in Iraq was one of the occasions that led to this displacement. And because of that, I think we can argue that the United States has some duty.

Q: Is this a duty just for the government, or is it for individuals as well?

A: Certainly there are government obligations. We have the capability to admit a larger number of asylum seekers. But we can’t solve the refugee problem by admitting all of these 60 million displaced people. What we can do is come to the aid of those countries hosting these migrants and displaced people to provide them with serious economic assistance.

Finding ways to contribute to policies that respond more adequately is a governmental duty. But we also have individual responsibilities. Many of the organizations that respond to those in most need are faith-based organizations connected with churches, synagogues, even increasingly with mosques. We can help that through our participation in our own religious community’s effort to respond.

Q: How do you answer those who say taking in refugees poses security risks?

A: There’s not a lot of evidence that terrorists have come into this country as refugees. Most of the people that have been involved in these terrorist activities are alienated young men who are westernized, but who have become alienated from the environment in which they’re living. Most of these refugees are either Muslim or African, and I don’t think it’s unfair to say that a certain kind of religious or racial antipathy toward those who are different from us is operative.

(A video version of this interview appeared on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly”)