GLOUCESTER, Mass. (RNS) On two walls in the sky-lit studio of artist Bruce Herman hangs a set of eight intimate portraits. Each face locks eyes directly with the viewer’s and won’t let go, as if crying out to forge a personal connection and unload a life’s story.

The effect is mesmerizing and makes each painting worth thousands. But admirers of Herman’s work aren’t going to find it for sale in any gallery.

That’s because this Christian artist has blazed an unconventional trail to success in the arts marketplace. In the process, he’s inspiring other religious artists who might have loads of talent but can’t break into the gallery scene.

[ad number=“1”]

“What people like Bruce do is they’re kind of clearing the way and showing the path,” said Cameron Anderson, executive director of Christians in the Visual Arts, a Madison, Wis.-based association of artists. “Younger generations ought to pay attention and see what they can learn.”

Herman, 64, bucks the stereotype of the introverted creator who makes art and then leaves it for others to sell and interpret.

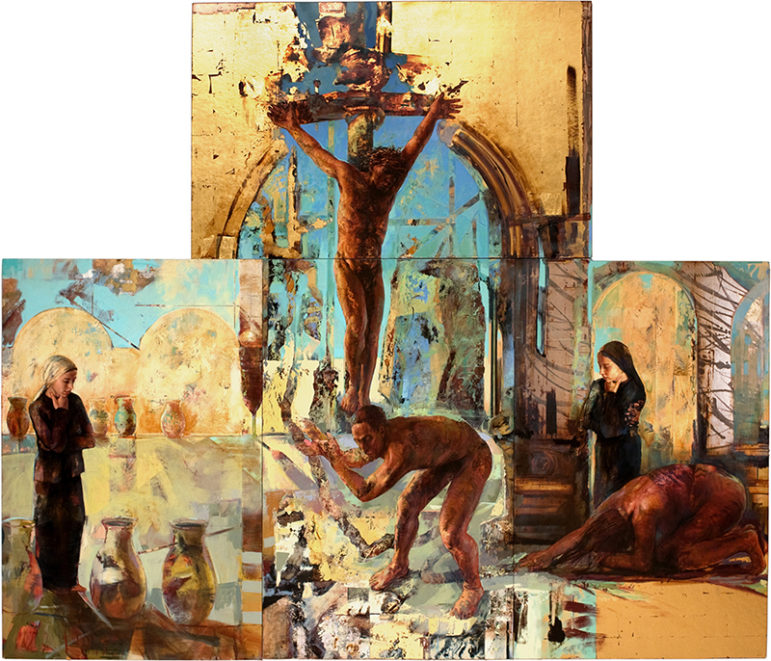

Riven Tree ©Bruce Herman, 2016, oil with gold and silver leaf on vertical triptych wood panels. Commissioned by Richard Hays, Dean of Divinity, Duke University. Photo courtesy of the artist

He relishes interlocutors who influence the creative process and later bring his work to life by engaging with it in free public venues such as museums.

“I don’t like to just simply express myself,” Herman said in an interview at his studio. “For me that’s not enough. I want to find out what my work is about by having them react to it.”

Most artists who enjoy commercial success rely on galleries to market their work, according to Anderson. Herman rarely shows in galleries and hasn’t been represented exclusively by one since the 1980s. But that doesn’t stop him from finding buyers for works priced anywhere from $2,000 to $80,000.

Artwork sales supplement his salary as chair of the art department at Gordon College in Wenham, Mass. And the relationships he builds with those who collect his art give texture to his vocation as a follower of Jesus. He views his career through a theological lens that regards communion, or unity, with God and neighbor as humankind’s highest purpose.

“I really want to make meaning, and I don’t believe I can have meaning by myself,” Herman said. “That probably is part of my Christian faith speaking there. I believe that communion is the ultimate reality, and communion is the ultimate meaning.”

[ad number=“2”]

Herman is able to avoid galleries and their 50-percent commission fees by taking advantage of other venues, such as museums where he receives no compensation for showing his work. His work has found showcases at the Vatican Collection of Modern Religious Art; the Cincinnati Art Museum; the Westmont Ridley-Tree Museum of Art in Santa Barbara, Calif.; and several university museums in the United States and abroad. Such settings increase his visibility and facilitate relationships that sometimes lead to direct sales or commissioned projects.

“Ordinary Saints” adorn the walls of Bruce Herman’s artist studio in Gloucester, Mass. RNS photo by G. Jeffrey MacDonald

By circumnavigating the gallery system, Herman is an inspiration to a growing cohort of Christian creatives who’re using visual art as a mode of praise or witness, according to Anderson. That’s because those who paint religious themes often get a cool reception on the gallery circuit.

“Organized Christian religion is looked down upon and not generally appreciated or respected in the high art world,” Anderson said. “Paintings, prints and sculpture that present the stories of the Bible would be thought of as irrelevant, cliché or maybe kitsch.”

Museums find benefits in working with Herman and embracing his identity as a Christian artist. The Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester owns four Herman paintings that aren’t explicitly religious and has exhibited many more. Because Herman is well-known in local Christian circles, his work draws attendees who might not otherwise visit the museum, according to Cape Ann Museum trustee Bill Cross. And Herman’s penchant for relational dialogue adds value for the institution.

“He is very gifted at discussing his art with a broad range of people in ways that make sense to them,” Cross said. “There are many artists who are not able to do that. Bruce has been able to understand where people may be able, emotionally and aesthetically, to access his art and engage with them where they are.”

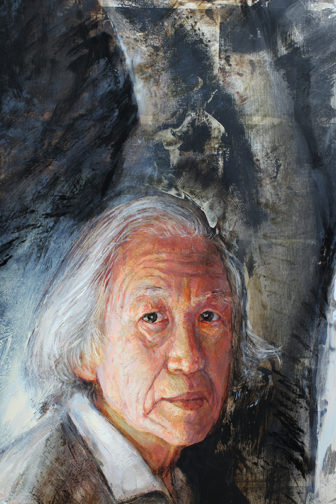

Second Adam ©Bruce, 2006; 125” x 155”; oil with gold and silver leaf on wood. Photo courtesy of Bruce Herman (http://www.bruceherman.com)

Herman’s paintings blend the realistic with the abstract and the explicitly religious with the universal. Of the 500 paintings he’s completed over 35 years, about one-third feature overtly Christian images, such as “Second Adam,” which depicts a crucified Jesus and a pensive Virgin Mary.

The rest aim to reveal God, he says, largely in the faces and forms of humans who are, according to Genesis 1:27, made in God’s own image. “Betrothed” depicts a woman in a tattered wedding gown against a cacophonic backdrop. He says she represents the church: damaged across history, but still beautiful, beloved and worthy of redemption. His “Ordinary Saints” series, which includes Osamu Fujimura (father of an artist friend),brings his loved ones’ arresting expressions to life. In each, observers get drawn into a vulnerable, unshielded gaze.

Portrait of Osamu Fujimura (detail of QU4RTETS No.4, Winter) ©Bruce Herman, 2012; 97” x 60”; oil and silver leaf on wood. Photo courtesy of Bruce Herman (http://www.bruceherman.com)

Welcoming dialogue opens doors to artistic opportunity for Herman. It also enables him to prosper in territory where other, less interactive artists might struggle.

That passion for partnerships got tested in 2015 after Duke Divinity School commissioned a $30,000 painting. It came with a challenge to depict Christ’s resurrection on a three-panel display, custom-tailored to a reading room nook above the Divinity School library.

An even bigger challenge came six months into the project. Professor Ellen Davis, who was overseeing the work, decided the work needed to be portable, not forever bound to one unique location. She asked Herman to change course and make instead a smaller, one-panel work. She braced for his reaction to such an unusual, costly request.

After sleeping on it, he agreed and reported his progress six days later.

“We’re moving forward in God’s grace,” Herman wrote to Davis in an email. “I’m actually quite excited about the new direction.”

She found in his response a Christian maturity that manifested as respectful, two-way communication for the duration of the project.

“He did literally wind up cutting up existing panels,” Davis said. “He was extraordinarily gracious about that.”

[ad number=“3”]

For all his success, Herman won’t be quitting his day job as a professor anytime soon. Nor does he worry that his artistic freedom is somehow limited by a web of marketplace expectations.

“He has his own sense of call and inspiration as to what he wants to do and paint,” said Walter Hansen, a Bible scholar and benefactor who commissioned the painting for Duke and endowed Herman’s chair at Gordon. “But he sees it as communication. If he doesn’t have the other side of the communication, there’s not completion of the process.”

(G. Jeffrey MacDonald is a freelance writer based in Boston)