(RNS) The headline in Time Magazine referred to “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” as “efficient and gray.”

The Huffington Post kicked it up a notch claiming, “(t)he entire film is about gray areas.”

“Screen Rant” explained that “Rogue One” is the most “real” of the “Star Wars” movies “because of morally grey areas.”

Director Gareth Edwards definitely had moral ambiguity in mind when making the film. The narrative behind his creative choices is, for many, so obviously true that it hardly needs mentioning. It goes something like this:

Those who came before us were naive and simplistic people. They believed in good and evil, light and dark. But today we are sophisticated. We have nuance. Instead of invoking stark concepts that give us easy answers, we have grown more comfortable living in the gray. Unlike those who went before us, we don’t mind moral ambiguity.

[ad number=“1”]

Edwards uses this narrative when naming the development of “Star Wars”:

“When they first made ‘Star Wars’ in the ’70s,” said Edwards, “the world maybe felt a bit simpler.” But “with the internet and global connection,” he said, “we know deep down that it’s not as simple as that.”

Maybe.

Or maybe movies and TV shows are being created with morally gray ideas and characters because that’s what makes entertainment companies money. From “Breaking Bad” to “House of Cards” to “Iron Man,” audiences love characters for their good and evil.

And though we like to think of ourselves as more sophisticated than folks from “the ’70s,” in truth this fascination with grayness and ambiguity can be found in the literary works of most societies. From Greek drama to Shakespeare to Mark Twain, the protagonists of the classics often have multiple layers and levels of moral complexity and ambiguity.

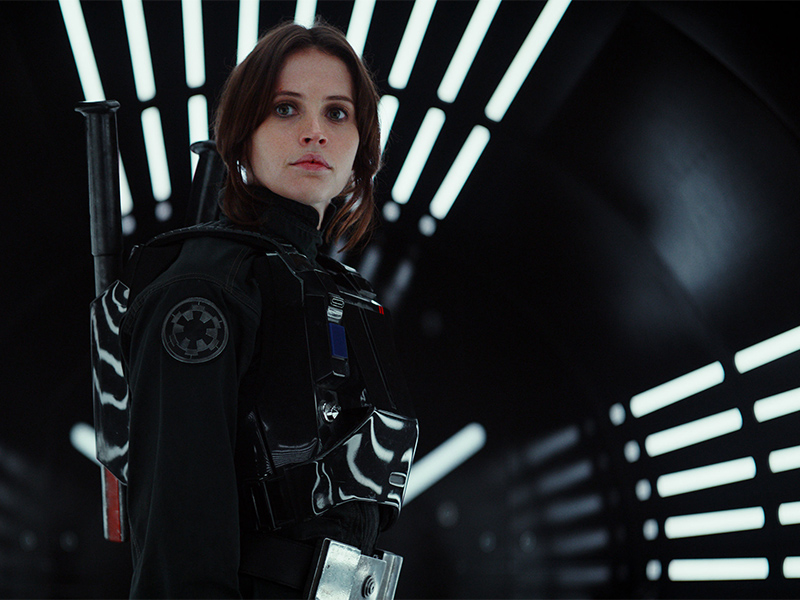

Felicity Jones plays Jyn Erso in “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.” Photo courtesy of Lucasfilm

George Lucas’ “Star Wars” is no exception.

He builds his main story arc around the moral complexity and ambiguity of Anakin Skywalker, his turn to Darth Vader, and the belief of Anakin’s wife and child that there is still redemptive good in him.

Han Solo is a shady hero who also drives the film while displaying substantial moral ambiguities. Lando Calrissian is in a similar gray zone, going from Judas at the end of “The Empire Strikes Back” to Rebel Alliance general in “Return of the Jedi.” Perhaps the most heroic Jedi of them all, Obi-Wan Kenobi, misleads Luke about his father and refuses to tell him that Princess Leia is his sister. The Rebels kill millions of innocent workers when they destroy the second Death Star battle station.

[ad number=“2”]

But while we might be interested in morally gray people, often the very evaluations that pronounce them such require clear moral judgments about actions. Indeed, some actions require the very simple judgments of “light side = good” and “dark side = bad” of George Lucas’ original trilogy.

Spoiler alert: In “Rogue One,” the first scene with Cassian Andor — who drives much of the film’s action as a Rebel intelligence officer — sees him murder one of his informants in cold blood. It is a disturbing look at his character, and it stains him throughout the film. We know he is a cold-blooded murderer, and though he does mostly good things in the rest of the film, he can never fully be “a good guy.”

But judging Cassian’s moral ambiguity as a character requires our rejecting moral ambiguity about his action: intentionally killing the innocent. There is no circumstance that justifies such a horrific act, just as there is no circumstance that justifies genocide, torture or slavery.

[ad number=“3”]

The original “Star Wars” trilogy was at pains to condemn all of these actions: the genocide of the people of Alderaan by the first Death Star, the torture of Han by Vader in Cloud City, and the enslavement of Leia by Jabba the Hutt.

So, if “Rogue One” is a story about morally complex characters, it falls within a well-established literary tradition. If, however, the message of the film goes beyond this to overturning previously black/white judgments about certain actions (like killing), then that is something new. And it is very bad.

At a time when war crimes in Aleppo are calling out for clear moral condemnation from the world community, we need to be holding onto our black and white, unambiguous moral judgments with all our strength.

Edwards acknowledged that Lucas’ goal in making “Star Wars” was to provide “a life lesson for kids.”

We live in a culture obsessed with the gray of moral relativism. In light of these considerations, “Star Wars” has a moral responsibility to live up to its longtime charge of teaching children that, while people often have various levels of ambiguity, the same cannot be said of certain gravely evil actions that should be always and everywhere condemned.

Reject the dark side. Follow the light. No exceptions.

(Charles C. Camosy is associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University and contributor to “The Ultimate Star Wars and Philosophy: You Must Unlearn What You Have Learned“)

Faithful Viewer logo. Religion News Service graphic by T.J. Thomson

Why the new ‘Star Wars’ movie could use some moral clarity

(RNS) Some actions require the very simple judgments of “light side = good” and “dark side = bad” of George Lucas’ original trilogy.

(RNS) The headline in Time Magazine referred to “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” as “efficient and gray.”

The Huffington Post kicked it up a notch claiming, “(t)he entire film is about gray areas.”

“Screen Rant” explained that “Rogue One” is the most “real” of the “Star Wars” movies “because of morally grey areas.”

Director Gareth Edwards definitely had moral ambiguity in mind when making the film. The narrative behind his creative choices is, for many, so obviously true that it hardly needs mentioning. It goes something like this:

Those who came before us were naive and simplistic people. They believed in good and evil, light and dark. But today we are sophisticated. We have nuance. Instead of invoking stark concepts that give us easy answers, we have grown more comfortable living in the gray. Unlike those who went before us, we don’t mind moral ambiguity.

[ad number=“1”]

Edwards uses this narrative when naming the development of “Star Wars”:

“When they first made ‘Star Wars’ in the ’70s,” said Edwards, “the world maybe felt a bit simpler.” But “with the internet and global connection,” he said, “we know deep down that it’s not as simple as that.”

Maybe.

Or maybe movies and TV shows are being created with morally gray ideas and characters because that’s what makes entertainment companies money. From “Breaking Bad” to “House of Cards” to “Iron Man,” audiences love characters for their good and evil.

And though we like to think of ourselves as more sophisticated than folks from “the ’70s,” in truth this fascination with grayness and ambiguity can be found in the literary works of most societies. From Greek drama to Shakespeare to Mark Twain, the protagonists of the classics often have multiple layers and levels of moral complexity and ambiguity.

Felicity Jones plays Jyn Erso in “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.” Photo courtesy of Lucasfilm

George Lucas’ “Star Wars” is no exception.

He builds his main story arc around the moral complexity and ambiguity of Anakin Skywalker, his turn to Darth Vader, and the belief of Anakin’s wife and child that there is still redemptive good in him.

Han Solo is a shady hero who also drives the film while displaying substantial moral ambiguities. Lando Calrissian is in a similar gray zone, going from Judas at the end of “The Empire Strikes Back” to Rebel Alliance general in “Return of the Jedi.” Perhaps the most heroic Jedi of them all, Obi-Wan Kenobi, misleads Luke about his father and refuses to tell him that Princess Leia is his sister. The Rebels kill millions of innocent workers when they destroy the second Death Star battle station.

[ad number=“2”]

But while we might be interested in morally gray people, often the very evaluations that pronounce them such require clear moral judgments about actions. Indeed, some actions require the very simple judgments of “light side = good” and “dark side = bad” of George Lucas’ original trilogy.

Spoiler alert: In “Rogue One,” the first scene with Cassian Andor — who drives much of the film’s action as a Rebel intelligence officer — sees him murder one of his informants in cold blood. It is a disturbing look at his character, and it stains him throughout the film. We know he is a cold-blooded murderer, and though he does mostly good things in the rest of the film, he can never fully be “a good guy.”

But judging Cassian’s moral ambiguity as a character requires our rejecting moral ambiguity about his action: intentionally killing the innocent. There is no circumstance that justifies such a horrific act, just as there is no circumstance that justifies genocide, torture or slavery.

[ad number=“3”]

The original “Star Wars” trilogy was at pains to condemn all of these actions: the genocide of the people of Alderaan by the first Death Star, the torture of Han by Vader in Cloud City, and the enslavement of Leia by Jabba the Hutt.

So, if “Rogue One” is a story about morally complex characters, it falls within a well-established literary tradition. If, however, the message of the film goes beyond this to overturning previously black/white judgments about certain actions (like killing), then that is something new. And it is very bad.

At a time when war crimes in Aleppo are calling out for clear moral condemnation from the world community, we need to be holding onto our black and white, unambiguous moral judgments with all our strength.

Edwards acknowledged that Lucas’ goal in making “Star Wars” was to provide “a life lesson for kids.”

We live in a culture obsessed with the gray of moral relativism. In light of these considerations, “Star Wars” has a moral responsibility to live up to its longtime charge of teaching children that, while people often have various levels of ambiguity, the same cannot be said of certain gravely evil actions that should be always and everywhere condemned.

Reject the dark side. Follow the light. No exceptions.

(Charles C. Camosy is associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University and contributor to “The Ultimate Star Wars and Philosophy: You Must Unlearn What You Have Learned“)

Faithful Viewer logo. Religion News Service graphic by T.J. Thomson

Donate to Support Independent Journalism!