This article is part of a series produced for Religion News Service’s parent organization Religion News Foundation with support from the Arcus Foundation and Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southern Africa. It emerged from a November 2016 journalism training workshop in Cape Town, South Africa.

YAOUNDE, Cameroon—Awono, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, fidgets and laughs uneasily as she describes her trip “to hell and back.”

“I was 16 when my father called me up for questioning. He is a police officer and criticized me for acting ‘too girly.’ I tried to make him understand that it was just who I am. The whole family was confused. They said I was not like that when I was growing up, but I argued they simply did not notice,” she said.

Awono, now in her early 30s, is a transgender woman in Yaounde, Cameroon.

“People attack me at home and steal my stuff,” she said. “Whenever the case goes to the police, they say they attacked me because I am of the LGBTI+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex] community, and [the perpetrators] get away with it.”

Brice Evina, President of the Cameroon Foundation for AIDS (CAMFAID), says the West African country has witnessed a recent spike in arrests and attacks targeting sexual and gender minorities. He describes the current situation as a “cemetery peace.”

“Some people may think LGBTI+ people live in peace in Cameroon. Their lives can only be compared to the peace and serenity of a graveyard,” he said. “They are silent but live in distress.”

Awono’s distress started in her teens when her father insisted it was a sin for a biological male to act “like a woman.”

“I was criticized for not doing what boys do, not playing football, for walking and talking ‘like a girl.’ I tried to hide my feelings. At the end of it all, my father sent me away from home,” she said.

Awono became homeless and struggled to make ends meet.

“I was ready to do anything for food and shelter. I ended up being raped by so many men I can’t even remember how many. When I fell sick, I couldn’t go to hospital for fear of rejection. I was obliged to call my mum on the phone and explain how natural my gender identity is. You know mothers have soft spots for their children,” she said.

Awono says her mother then rented a house for her and sent her back to school where she became “married” to her education.

“I knew it was my only chance for survival,” she said. “I went through lots of things, and today, I am a happy woman.” Yet Awono and other gender and sexual minorities in Cameroon face new challenges every day.

“Right now, we only hang out in particular bars, which are LGBTI+-friendly,” Awono said.

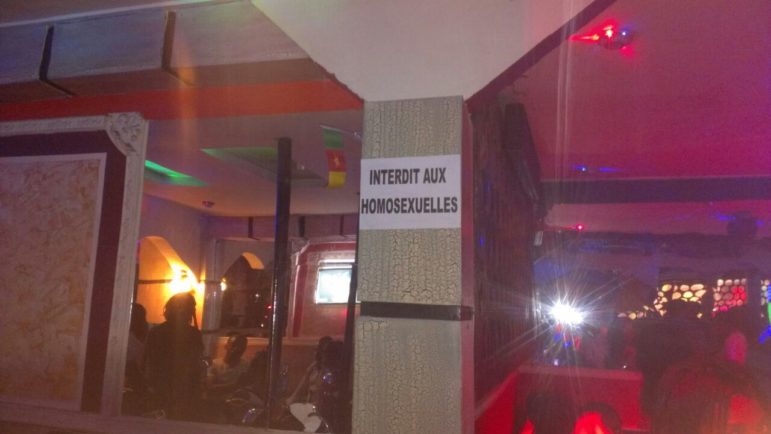

The number of such spaces shrunk recently when a formerly friendly pub posted a sign forbidding access to “homosexuelles.”

“We find that disturbing, but what can we do? The bouncers see you from a distance and ask you to walk away. They have a database with our photos. Even when they find you sitting, they ask you to leave,” she lamented.

Serge, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, has faced ostracism and violence in Cameroon because of his sexuality. When his family learned he was gay, they prayed to cast out the witchcraft they believed possessed him.

“People come preaching and asking you to stop sleeping with men and telling you how sinful it is. At the end of the day, they still take your ‘evil’ money when they need your help,” he said. “I know parents who only accept their children’s sexuality when they start earning a living. But when you die, they call you names and say you probably died of some of ‘those LGBTI+ diseases.’ What a pretentious world.”

Serge says he was attacked at his apartment in October 2015.

“When we got to the gendarmerie, the attacker admitted he wanted to kill me because I was gay and claimed I was having sex with his younger brother,” Serge said. “The following day, I was shocked. A TV crew from the CRTV national broadcaster was brought in, and I was in the news. During a chamber hearing, the judge insisted I was gay and guilty because I work for an NGO that advocates for LGBTI+ rights.”

Serge was eventually released without charge. His attacker remains in jail.

Serge believes his release is unique and that other sexual and gender minorities in Cameroon would likely still be in custody after being attacked.

Human Rights abuse

In 2013, when Cameroon’s human rights record was reviewed at the U.N. Human Rights Council, 15 nations urged the country to improve its treatment of LGBTI people.

Cameroon’s network of human rights advocates agree that Article 347-1 of the Penal Code runs contrary to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and even Cameroon’s constitution, which guarantees freedoms and condemns all forms of discrimination including that based on gender.

Article 347-1 prescribes fines of up to 200,000 Central African Francs (about $320) and prison terms of up to five years for anyone who has sexual relations with someone of the same sex.

Emmanuel Mbanmi Ndinga, a member of parliament in Cameroon’s Northwest Province, says not everything in international conventions or charters should be implemented in local law.

“We cannot implement aspects that are repugnant to our cultures,” he said of equal rights for sexual and gender minorities.

CAMFAID Human Rights Coordinator Jean Jacques Dissoke says Cameroon’s anti-LGBTI legal framework promotes discrimination.

When people are charged under Article 347-1, it becomes difficult to find lawyers willing to defend them publicly. Some even abandon court proceedings mid-trial due to scrutiny and stigma.

CAMFAID has recorded 50 arrests under Article 347-1 since 2012. In late-November 2016, gendarmerie officers raided a house in Yaounde and arrested 12 suspected sexual and gender minorities who were living together.

“We do not have enough funds to follow up on their cases. It is funny how people think that being of the LGBTI community or defending the rights of sexual minorities is always about money,” Dissoke said, citing a common trope that Western donors funnel money to Africa to “promote and recruit unAfrican notions of sexuality.”

Although Cameroon’s sexual and gender minorities face stigmatization, verbal aggression and criminalization, Evina says local human rights advocates have successfully improved their access to health facilities and services.

“We sensitize prison wardens and medics on the health needs of the community. At times, gay persons go to hospitals and are denied medical attention. In some cases, we go there and sensitize the medics, and they agree to treat the patient when he returns.”

Awono is familiar with such discrimination but says she feels none when she visits her local Catholic church.

Cardinal Christian Tumi, archbishop emeritus of Douala, has on several occasions reminded congregants that his church does not excommunicate sexual minorities. He insists that all humans sin and that homosexuality should not be singled out as a bigger sin than others.

In a 2015 interview with the Catholic Church newspaper L’Effort Camerounais, Tumi said, “In imitation of Christ, the Church has never condemned a sinner.”

Bleak future?

In January 2013, Cameroon’s President Paul Biya told journalists “there’s no reason to despair…Minds are changing,” with regard to LGBTI issues. Six months later, the founder of CAMFAID Eric Lemembe was found dead at his home.

Freedom House reported that Lemembe’s “neck and feet had been broken and his face, hands and feet had been burnt with a hot iron.” The killing, according to the American NGO, was a demonstration of ignorance, prejudice and laws that deny LGBTI people in Cameroon their fundamental rights.

Cameroon’s Communication Minister Issa Tchiroma held a press conference and condemned Freedom House for requesting equal rights for LGBTI people. Tchiroma said Cameroon is made up mainly of Christians, Muslims and traditionalists whose beliefs are against such rights. He also added that a criminal offense cannot be promoted.

Three years later, Cameroon still has a long way to go to reach equality for gender and sexual minorities, but Awono and Serge are hopeful for the future.

“Inasmuch as issues of human rights will always exist in our society, I am happy that we now have organizations that will always be there to promote and defend these rights, especially those of sexual minorities,” Serge said.

Mbom Sixtus is a journalist based in Yaounde, Cameroon.