(RNS) Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. issued his prophetic denunciation of the war in Vietnam from the pulpit of Riverside Church in New York City.

As his biographer David Garrow recalls in The New York Times, the speech drew harsh criticism from the media that had earlier celebrated his civil rights campaign, including the Times itself. But King, who had been deeply concerned about the war for some time, saw opposition to it as a necessary extension of his earlier public witness.

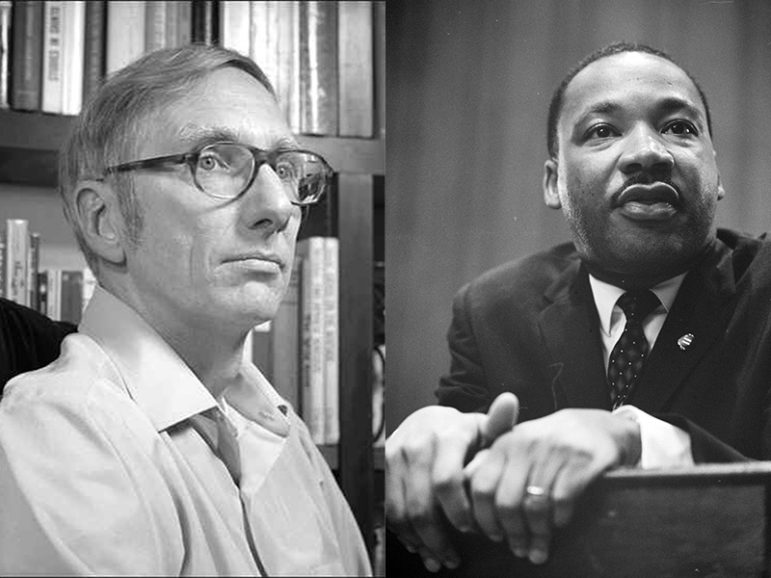

Martin Luther King Jr. discusses his opposition to the war in Vietnam at Riverside Church on April 4, 1967.

In saying plainly that the country was wrong to be in Vietnam, King may have been out in front of mainstream opinion but he was not all by himself. Among the leading academics opposed to the war was Robert Bellah, a sociologist of religion then about to depart Harvard for Berkeley.

The intellectual quarterly Daedalus featured Bellah’s seminal article “Civil Religion in America” in its winter 1967 edition. I believe King read the article — the first one in an issue on “Religion in America” — and that it helped shape his speech at Riverside on April 4, 1967.

Bellah’s main purpose was to make the case for “an elaborate and well-institutionalized” American civil religion existing “alongside of and rather clearly differentiated from the churches.” But his underlying concern was about how that religion would adapt to the “time of trial” represented by the war in Vietnam.

“Gradually but unmistakably,” he wrote, “America is succumbing to that arrogance of power which has afflicted, weakened and in some cases destroyed great nations in the past.”

In similar terms, King talked about how, after World War II, “we fell victim as a nation at that time of the same deadly arrogance that has poisoned the international situation for all of these years.”

Robert Bellah in Berkeley, Calif., on May 16, 2008. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons/Andreas Guther

Bellah wrote: “Without an awareness that our nation stands under higher judgment, the tradition of the civil religion would be dangerous indeed.”

King echoed that: “God has a way of standing before the nations with judgment and it seems that I can hear God saying to America, ‘You’re too arrogant!'”

Bellah concluded his article with a call for remaking American civil religion into something greater — a world civil religion.

“It is useless to speculate on the form such a civil religion might take,” he wrote, “though it obviously would draw on religious traditions beyond the sphere of biblical religion alone.”

King likewise expressed the need for a more comprehensive spiritual ethos, but he was not afraid to speculate on the form it should take.

A genuine revolution of values means in the final analysis that our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies. This call for a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class, and nation is in reality a call for an all-embracing, unconditional love for all men.

This love was not just Christian nor, in the common language of post-World War II ecumenism, Judeo-Christian. It was, said King, a “Hindu-Muslim-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief about ultimate reality.”

In later years, fellow academics often criticized Bellah for promoting a sacralized version of American national identity. A few months before he died in 2013, he sent me an email about an article I’d written that mentioned “Civil Religion in America” in which he complained about being misunderstood.

In spite of the fact that my article is profoundly critical of America and came out of a period of deep opposition to the Vietnam War, it has been widely interpreted as a hymn to religious nationalism, something I above all hate. I discovered in some of my journeys of the last two years that I am understood in such places as China and Germany as exactly the opposite, that is my use of the civil religion idea is seen as an alternative to religious nationalism, not a form of it, and that, since it is based on civil society and not the state, is seen as democratic and open to ongoing argument and criticism. Some (intelligent) Americans have seen that, but far too many put me together with Pat Robertson, to my horror.

Among the Americans who did not misunderstand Bellah was King.

(Mark Silk writes the Spiritual Politics column for RNS)