I admit it: for decades, I have been Sharpton-phobic.

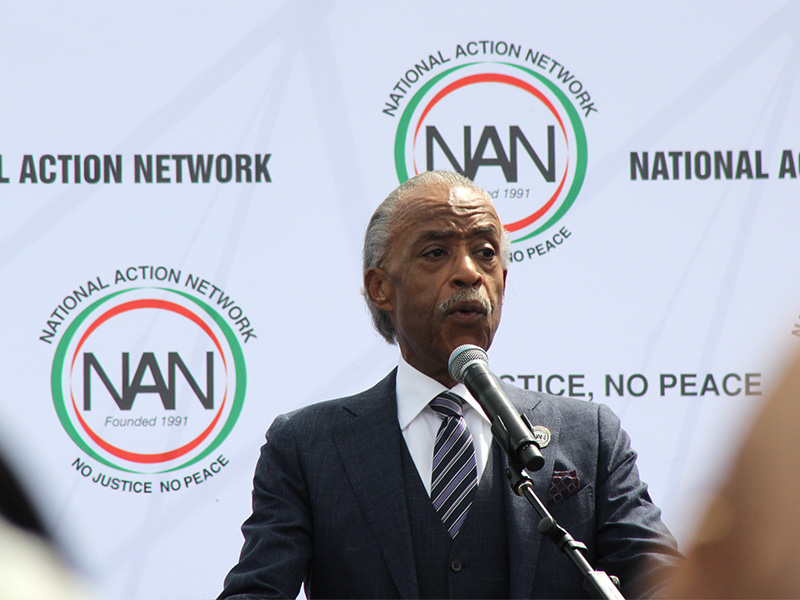

I am talking, of course, about Reverend Al Sharpton, the civil rights activist.

I saw the photos of my friends and colleagues marching with him yesterday in Washington, DC, as part of the Thousand Ministers March against hatred and bigotry, and I must admit that I was troubled.

I remember how Reverend Sharpton was a willing participant in one of the greatest public outrages in recent historical memory – the Tawana Brawley case.

In 1987, in the Hudson Valley, a black teenager, Tawana Brawley accused four white men, including an assistant district attorney, of raping her. It became a nationally known case. Reverend Sharpton was among those who took her side.

It became clear that she had lied, and that the reputation and career of the prosecutor had been needlessly destroyed. Sharpton paid a fine for his role in this deception. To be fair, at the time, he had believed Ms. Brawley. But, there is no record of him apologizing to the man whose life was damaged.

And then, several years later, in August, 1991, in Brooklyn, a motorcade was driving the late Lubovitcher rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, to the cemetery to visit his wife’s grave. A car accidentally ran over and killed a young black boy, Gavin Cato.

Reverend Sharpton spoke at Gavin’s funeral. When he described the Jews, he referred to “diamond dealers.”

The death of Gavin Cato sparked the Crown Heights riots, in which Yankel Rosenbaum, a 29 year old Orthodox Jew from Australia, was killed.

On the third day of the riots, Sharpton was among the leaders of a march through Crown Heights. The marchers carried anti-Semitic signs, and an Israeli flag was burned.

Edward S. Shapiro called the Crown Heights riot “the most serious anti-Semitic incident in American history.” People called it a pogrom. It ultimately contributed to the defeat of New York City Mayor David Dinkins.

So, you can see why I have not been a fan of Reverend Sharpton. I am far from alone. Many still hold onto that anger.

But, there is another side of my soul.

It is now Elul, the season of repentance.

What would any possible repentance on the part of Al Sharpton look like?

Friends who were present at the march in Washington, DC have praised Reverend Sharpton’s public statements of unity and reconciliation between Jews and blacks.

Sharpton said: “We should never forget that it was Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner that died together — two Jews and a black — to give us the right to vote.”

Sharpton spoke of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched with Dr. King at Selma, and he was open about the fact that his path has not always been strewn with roses:

We have had days good and bad, but from this day forward . . . we’re going to make sure we do our part to keep this family together…You’re going to see the victims of Nazism, the victims of white supremacy, march to the Justice Department and say we don’t care what party is in, we are not going to be out. We are coming together like Dr. King and Abraham Heschel did, like Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner did.

How should we now think about Reverend Sharpton?

First, I cannot “forgive” Reverend Sharpton, because he did not sin against me.

Rather, he sinned against the man whose life was ruined in the Tawana Brawley affair. He sinned against the victims in Crown Heights.

It would be incumbent for Reverend Sharpton to publicly admit his wrong doing and to ask forgiveness of those whom he has hurt.

But, let’s consider the possibility that Sharpton has changed. True – he is not the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., but how often in history does that kind of leader emerge? (May it happen again, soon).

Which begs the question: what is the statute of limitations for the bad things that we do? What is the statute of limitations for destroying a person? What is the statute of limitations for being part of the incitement of what amounted to an American pogrom?

In fact, Sharpton learned from the Tawana Brawley experience. He resolved to never again engage in ad hominem attacks.

According to the great sage Maimonides, this is one of the proofs of repentance. We encounter the same situation, and we choose to act differently.

There is a final reason why I am considering moving on from my animus towards Al Sharpton.

The events of recent months have reminded all of us of a very powerful and troublesome and even redemptive truth.

Jews and blacks are joined together at the hip.

The same people who hate blacks, hate Jews.

It is tempting to continue to focus on Sharpton’s past.

But, it is also possible that focusing on his past is a distraction from the realities of the present, and our hopes for the future.

We have a lot of work to do. We need partners in that work.

The question is: who should be our partners? And how do we navigate through the assorted differences and disagreements that we have?