EDITOR’S NOTE: This column originally appeared in Sightings, a publication of the Martin Marty Center at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings in your inbox on Mondays and Thursdays. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

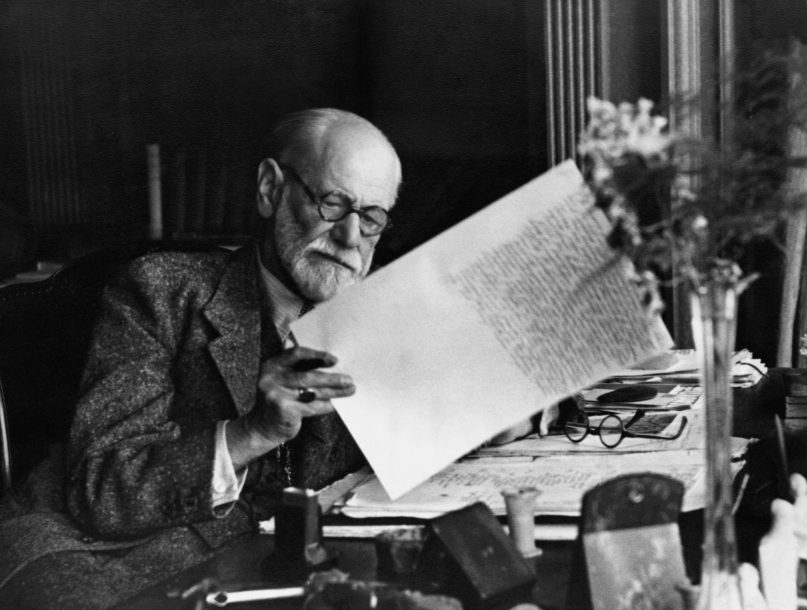

Darwin-Marx-Nietzsche-Freud—dubbable, and sometimes dubbed, “the four bearded god-killers”—who framed now-classic, career-long attacks on God and gods and religion and religions, enjoy and suffer successions of varying critical fates. We will save Nietzsche and his “death of God” for some future column. What prompts this week’s look at these titans is the headline—typical of many in recent weeks—“Why the Freud Wars Will Never End” in The Wall Street Journal. In a recommendable review by Adam Kirsch, Frederick Crews’s Freud: The Making of an Illusion (Metropolitan, 2017) and its subject’s ever-changing fate get full attention.

Kirsch quotes poet W. H. Auden on Freud after Freud’s death in 1939: “to us he is no more a person / now but a whole climate of opinion.” Yet Auden on the same page wrote of Freud that “often he was wrong and, at times, absurd.” Kirsch cites an absurd, even bizarre, theory of Freud’s but goes on to ask why, despite such, “we” have to take him seriously still. He quotes Crews’s new book, along with others by the same author, as the latest installment in the “Freud wars,” waged mainly in the 1980s and 1990s. The book is intended not just to debunk and defame Freud, but to banish him from serious discussion.

Kirsch cites index references in Crews: “Freud, Sigmund … abandoned by patients; alcohol, recourse to; bribery on behalf of; impotence of; vindictiveness of,” and more, including references in the book to Freud as a liar who was guilty of incest and adultery, etc. The author correctly notes that Freud does not belong in the company of scientists, where generations of Freudian counsellors once located him. Instead, “he resembles Karl Marx more than, say, Charles Darwin, to name two figures who dominated the intellectual world of his youth.” So it was because he “was a kind of prophet that he was so hostile to all forms of traditional religion … If there is one constant in Freud’s intellectual life, it is his adamant opposition to religion, especially the Judaism that was his family’s tradition.”

Kirsch sees Crews’s Freud as liar and cheat and hoax, “a false prophet.” Yet, “like other exploded belief systems, psychoanalysis is so deeply embedded in our cultural self-understanding that it may be impossible to think our way entirely free from it.” He “cannot be ignored, only argued with and about—which suggests that the Freud wars may be with us to stay.” The same might be said of those myths that began as, but went beyond, economic science. Take Karl Marx, whose Communist myths suffer after having fortified, and fortifying, murderous political and military expressions.

We also listed in the company of the god-killers Charles Darwin, who like the others mixed science and myth, and became controversial in the religion he left behind, Christianity, which had very different accounts of human origins and destiny. He, too, “cannot be ignored, only argued with and about,” and so the Darwin wars “may be with us to stay.” Many people of faith, including theologians, pick and choose elements in some of these rivals, considering that they cannot be ignored, but can be argued with across the spectrum of alternatives. They do not ignore the god-killers, but learn to be selective and to transform features of them, without themselves becoming “prophets” of such belief systems, however much these seem to be here to stay.