(RNS) — Two days after he was nominated by President Trump to the Supreme Court, Judge Brett Kavanaugh ladled mac and cheese into takeout trays outside Catholic Charities in Washington, D.C.

That the nominee for the country’s highest bench should pop up in photos volunteering for a Catholic aid group is no surprise at this point. When Trump announced his selection, Kavanaugh talked about being “part of the vibrant Catholic community in the D.C. area … united by a commitment to serve.” He also gave a nod to schooling: “The motto of my Jesuit high school was ‘Men for others.’ I’ve tried to live that creed.”

Kavanaugh’s inclusion on the court would preserve the Catholic majority, with six justices reared and formed in that tradition. (Neil Gorsuch attends an Episcopal Church but grew up Catholic and attended the same Catholic high school as Kavanaugh.)

Judge Brett Kavanaugh. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

The remaining three justices are Jewish.

The Supreme Court that may yet rule on the current administration’s fractious immigration policies, in other words, is dominated by two religious minorities that came into this country as immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries and strained to gain a footing equal to that of the Protestant establishment.

“For a whole lot of Catholic and Jewish immigrants, law school was, in a very pressing way, a ticket to the middle class,” said Richard W. Garnett, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame.

In addition, Catholics and Jews both struggled with religious prejudice and may have seen the legal profession as a way to ensure that their rights were protected.

Today, Catholics make up a declining share of Americans — just 20 percent, according to Pew Research (down from 23.9 percent a decade earlier). Jews are a far smaller number — barely 2 percent.

The United States has elected only one Catholic president (John F. Kennedy) and one Catholic vice president (Joseph Biden). It has had no Jewish presidents or vice presidents.

So, why their dominance on the court?

It may have something to do with the value the two minority faiths place on higher education and the religions’ openness to intellectual inquiry, said John Fea, professor of American history at Messiah College.

“Unlike evangelicals who base their entire worldview on the teachings of the Bible, Catholics and Jews seem much more open to engaging in larger principles that will affect not only their own community, but the common good of the republic or of a nation beyond the needs of their particular religious tradition,” Fea said.

For most of America’s history, the court was composed almost entirely of Protestants.

The first Catholic to win a seat on the court was Roger Taney in 1836 — nearly 50 years after the court was created. It would take another 58 years for the second Catholic to be elevated to the Supreme Court.

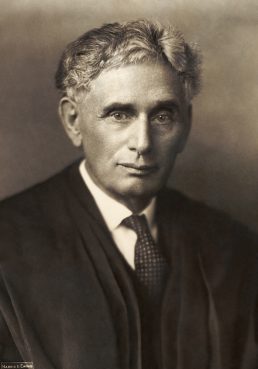

Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jew on the Supreme Court. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

It took 127 years for the first Jew to take a seat on the court. Louis Brandeis, the son of Jewish immigrants from what is now the Czech Republic, was elevated to the position in 1916. There was blatant anti-Semitism during confirmation hearings that lasted six months. Afterward, some justices refused to sit next to him for the official court photo.

“There were all sorts of smears against his character,” said Paul Brandeis Raushenbush, Brandeis’ great-grandson and a senior vice president at Auburn Seminary. “It was an overt anti-Semitism paired with this concern for nativist ideas.”

Seven other Jewish justices followed Brandeis, who was later hailed by President Franklin Roosevelt as his “Isaiah.” There have been 13 Catholics — not counting Gorsuch.

During the 20th century, it was assumed there would be a “Catholic seat” and a “Jewish seat” on the court, so that when one retired, or died, another of the same faith would be appointed.

But that desire to keep a certain religious diversity on the court is no longer in play.

Ideology and politics seem to play a larger role. Consider that Democratic presidents appointed seven of the eight Jewish justices. (Benjamin Cardozo, the second Jewish justice, was nominated by Herbert Hoover, a Republican.)

“Partly that’s reflective of the American Jewish community and its relationship with more liberal or progressive political parties,” said Lauren B. Strauss, professor of Jewish history at American University.

Republican presidents have selected the recent crop of Catholic justices — with the exception of Sonia Sotomayor, an Obama appointee. Those Republican presidents have wanted to shape the judiciary in a more conservative direction.

“Part of the story may also be the rise in significance of the abortion question on the court,” said Garnett. “It’s not the whole thing, but part of it.”

Many have speculated that if Kavanaugh is confirmed by the Senate, Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court ruling that allowed women the right to an abortion, may be overturned.

Those political or ideological headwinds may partly explain the court’s Catholic-Jewish makeup.

Experts say that as more evangelicals gain entry to elite law schools and start clerking for top judges, they too will begin getting nominated to the top court.

But the nation’s religious makeup is also changing. Soon the number of religiously unaffiliated Americans is expected to overtake the number of evangelicals in the country.

Nearly 23 percent of Americans are now unaffiliated, almost as many as those who are evangelical (25.4 percent).

“We’d like to see a court that’s more reflective of the country and of people who do not hold religious beliefs,” said Alison Gill, legal and policy director for American Atheists. “There are a growing numbers of young people identifying as atheist or agnostic. It’s just a matter of time.”