OJAI, Calif. (RNS) — They come by the dozens, making their way past groves of orange trees and converging on a low-slung white house with a gnarled pepper tree in the front yard.

Three Saturdays a month, people from all over Southern and Central California gather in this small town east of Santa Barbara to ask fundamental life questions: How can humans control their emotions? Is it possible to live without fear? What does it mean to be “whole”?

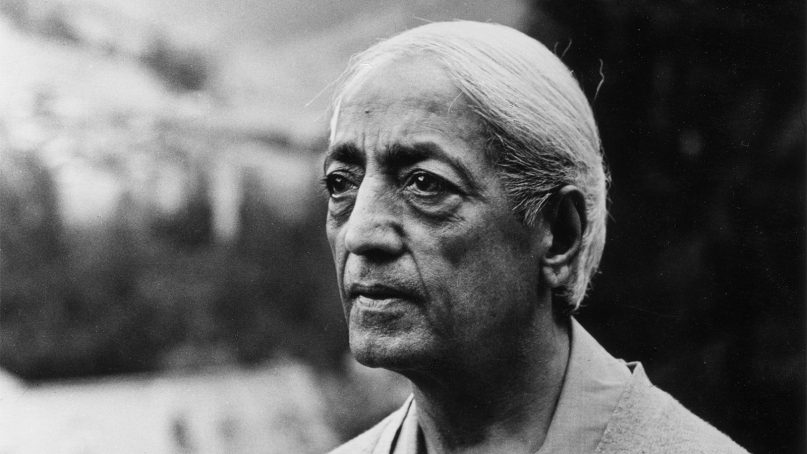

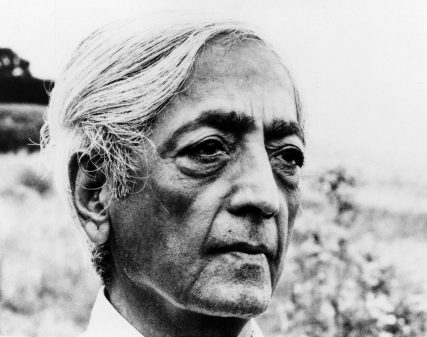

They’re here because of Jiddu Krishnamurti, an Indian philosopher, speaker and writer who made Ojai his home and left this property to the Krishnamurti Foundation of America after his death on Feb. 17, 1986.

Today, the complex is one of eight educational centers around the world where Krishnamurti’s followers, drawn by his message to question established doctrine, hope to change the way people think about their religious beliefs. And using a network of schools, youth programs and dialogue groups, the foundation is working to diversify its reach to include a younger audience.

Krishnamurti was born in 1895 in southern India and was raised as a Theosophist — an esoteric religious group that drew inspiration from Buddhism and Hinduism. Though he was groomed to be a leader in the movement, Krishnamurti eventually rejected Theosophy and began traveling the world, speaking to groups of young intellectuals about his denial of organized belief systems.

He eventually made Ojai, which he first visited in 1922, his base, drawn to its serenity and mild climate.

A tractor is parked among orange trees at the Krishnamurti Foundation of America in Ojai, Calif. RNS photo by Diana Kruzman

The KFA does not consider itself a spiritual organization — though Krishnamurti himself was a “deeply religious, spiritual person,” said Michael Krohnen, the librarian of the foundation. Instead, Krishnamurti encouraged his followers to question the reasons behind their beliefs and come to their own conclusions about their faith.

“It has a great rational element,” Krohnen said in a recent interview with Religion News Service, surrounded by books by Krishnamurti and those who knew him. “Belief means you accept something that you don’t really know, that you don’t have proof of. But at the moment people start questioning these things, Krishnamurti speaks to them.”

Krohnen first met Krishnamurti in 1975, as a young student from Germany. “I saw Krishnamurti as a modern-day Buddha,” he said. “There seemed to be a real presence there, a sense of nonhurriedness about him.”

He and many others were drawn into Krishnamurti’s orbit. The philosopher’s house in Ojai played host to frequent discussions about the nature of consciousness and religion and hosted visitors from around the world, including Aldous Huxley, Jonas Salk, D.H. Lawrence and Jackson Pollock.

Today, Krishnamurti’s message fits into a growing trend of disengagement with religious establishments, said Richard Flory, a sociologist who studies religious and cultural change at the University of Southern California.

“Religion is becoming more personalized and internalized,” Flory said. “People are customizing what they believe and practice to make it fit into their lives, rather than fitting their lives into the religion.”

More than a quarter of Americans now identify as “spiritual but not religious,” according a 2017 Pew Research Center study — up from 19 percent in 2012. As growing numbers of people become disillusioned with organized religion, groups like the KFA offer a chance to examine one’s true beliefs without the burden of orthodoxy.

“It’s another option out there for people,” Flory said. “There’s a marketplace of religious thought out there, and those who are interested will seek it out.”

Jiddu Krishnamurti in 1972. Photo by Mary Zimbalist. Copyright the Estate of Mary Zimbalist

At the eight centers across the United States, India and the United Kingdom, children are already exposed early on to Krishnamurti’s “inquiry-based” form of education. But, recognizing that the current climate is favorable to questioning, the Krishnamurti Foundation has recently begun sending members to visit high schools and universities including UCLA, UC Davis, UC Santa Cruz and Golden West Community College to engage students in discussions about self-improvement.

Older seekers tend to fill up the Saturday Dialogues at the center in Ojai, which serve as an introduction to Krishnamurti’s teachings for those who never cottoned to religion in the first place. For this mature demographic, Krishnamurti’s teachings provide an opportunity for self-reflection — and the chance to meet other followers of his method. Ojai resident Kevin King, 53, said he has been coming to Saturday Dialogues for the past several years “for the people.”

But others are drawn to Krishnamurti precisely because they’re looking for a deeper meaning that religious practice can’t provide, said John Duncan, a facilitator for the Saturday Dialogues.

“People are being pulled away from religion to begin with — that’s happening on its own,” said Duncan, 55. “You wouldn’t come here if you were already a Christian and that was working for you.”

Krishnamurti’s central philosophy, Krohnen said, is one of negation — pointing out what one knows to be false, while not clearly offering any answers to replace it.

“Krishnamurti doesn’t really give a method,” Krohnen said. “Except to be observant, but don’t judge. There’s no end to it, really — it’s something that goes on for the rest of one’s life.”