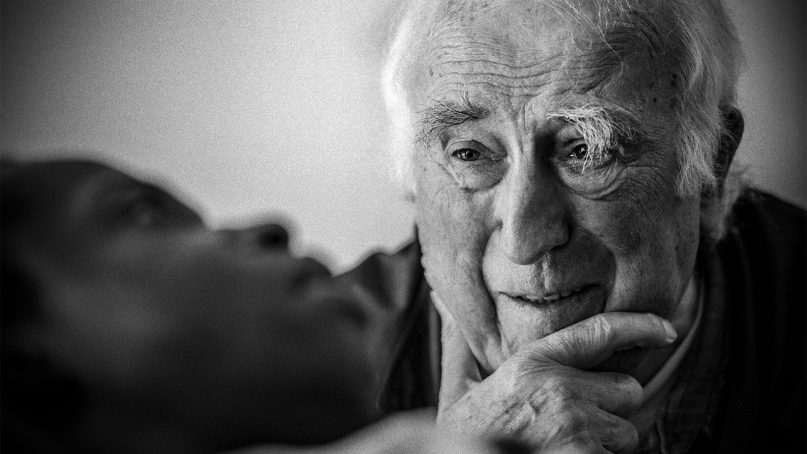

Jean Vanier visits Sebastien, a young man whose injuries in a car accident left him with profound cognitive and physical disabilities, at the L’Arche care home in Trosly-Breuil, France, in 2015. Photo courtesy of Summer in the Forest/R2W Films

(RNS) — Thirteen years ago this week, I met a man — a living saint, many insisted — who broke my heart and forever changed my life.

Jean Vanier, the Canadian theologian, philosopher and humanitarian who died Tuesday (May 7) at the mighty age of 90, was just 77 years old when our paths crossed in Chicago on a glorious spring day in May 2006.

Vanier, the founder of L’Arche, an international network of small communities where adults with intellectual and physical disabilities and those without them live, work and care for each other, was in town from his home in France to accept a Blessed Are the Peacemakers Award from one of the city’s many seminaries.

As religion writer for the Chicago Sun-Times at the time, I was dispatched to cover the great man’s public address.

Running late, I arrived at the Catholic Theological Union just as Vanier was introduced to the standing-room-only crowd and walked toward the microphone.

I plopped down on the floor cross-legged not far from the dais, grabbed my reporter’s notebook, turned on my audio recorder and started taking notes.

Just another day in the life of an ink-stained wretch, I thought.

But then, Vanier started talking.

About 10 minutes into his address, Vanier began to tell the story of a serial killer — a man imprisoned for murdering five women.

I leaned in, wondering where he was going with this unexpected narrative.

“He needs someone who will see that behind all those walls that have been created, there’s a little child who has never been awakened,” Vanier, a towering man with a slight stoop that made it seem as if he were bowing to everyone he met, said with characteristic quiet gentleness.

“Will one day he find somebody who will reveal to him his beauty? That he is a child of God? That he is precious?”

Jean Vanier, the founder of L’Arche, an international network of communities where people with and without intellectual disabilities live and work together, gestures as he talks during a news conference in London on March 11, 2015. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis)

The idea that a serial killer, despite the sins and horrors he has perpetrated, remains precious to God and should, Vanier seemed to suggest, also be precious to us, touched me in such a profound way I scarcely have appropriate words to describe it all these years later.

It was as if Vanier’s radical compassion broke something in my soul that needed to be broken. It widened the aperture of my heart, making room to accommodate a love more expansive than I thought myself capable of feeling or giving.

“The quest is not just believing in God, but believing in other people,” Vanier continued. “Believing in ourselves as children of God, and that we are called to see other people as God sees them, not as we would like them to be.”

This can be done only when we are in relationship with another, when we take the time to connect, to listen — really listen — to what someone is saying, to hear the story behind the story, he said.

“Tell me your story, your pain, your suffering, your cry, your needs,” Vanier said. “Tell me about your childhood, tell me what you maybe remember. Tell me. Tell me your dreams. Tell me your hopes.”

Vanier started L’Arche (“ark” in French) in 1964 after learning about what many people with disabilities suffered in psychiatric hospitals and other institutions at the time.

He invited two men with disabilities to live with him in his small home in Trosly, about 60 miles north of Paris. He thought he was doing a good deed for the two men, Philippe Seux and Raphael Simi.

Over time, Vanier learned it was not for, but with Seux and Simi, his friends and equals.

Today L’Arche has more than 150 homes in 37 countries.

As I listened to Vanier, I began weeping into my reporter’s notebook, breaking a cardinal rule of journalism in front of a gaggle of other reporters and a room full of strangers.

More than a decade later, I’m wiping tears from my eyes as I write this in a packed coffeehouse in Boise, Idaho, the day after Vanier passed from this life to the next.

Jean Vanier. Photo courtesy of Templeton Prize, John Morrison

Since our first meeting more than a dozen years ago, Vanier and I corresponded a few times.

In one of his notes to me, written in his compact, careful cursive, he said: “You sound sad, Cathleen. But I hope that you are not.”

I cannot remember what was going on in my life at the time or what I’d written that might have given him that impression. Perhaps it was nothing I’d written or said. Vanier simply might have known something was up, sensing a disruption in the force from thousands of miles away.

He wanted me to know that he was listening, that he sees me, that I was and am beloved.

Confronted by that kind of love and grace — the undeserved gift we cannot earn or merit, but that is given to all equally — the natural impulse is to pay it forward.

To take a small risk or a leap of faith; to extend love to someone else.

And to learn, as Vanier discovered, that a single act of kindness has the power to change your life — and the world.

The reason I was late arriving at Vanier’s Chicago speech that afternoon in May 2006 was a call I’d received as I was driving to the seminary.

The voice on the other end of the phone told me that I’d won a raffle for a two-week trip for two to Africa.

A month or so earlier, I’d bought a handful of raffle tickets from a newspaper colleague who was climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania as a fundraiser for a small NGO in Chicago called the Global Alliance for Africa.

As I’d written occasionally about Africa — the AIDS emergency in sub-Saharan Africa, the genocide in Darfur, various international aid efforts throughout the continent — my colleague rightly surmised that I’d be game to support the cause.

Winning the raffle (a first for me) felt like a huge gift of grace, like a door opening unexpectedly to a new adventure, a new reality. Looking back now, I had no idea where it would lead. But I am certain that meeting Vanier minutes later gave me the operating instructions for when I arrived.

A year later, my husband and I took that prized trip to Africa, where we visited Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi. While we were in the latter, we met a little boy named Vasco who had lost his biological parents to the AIDS pandemic and, for an extended period of his young life, lived on the streets begging for money and food.

He had been born with a heart defect and was gravely ill.

We’d almost missed him.

On the way back to our hotel, a guide from an organization that worked with street children with whom we’d spent the day asked us if we’d mind meeting one more kid.

“He’s just kind of special,” the man said.

“Sure, why not?” was our answer.

We saw him and quickly realized something was wrong.

I thought of Vanier and what he would do, what he would say. We tried to get Vasco medical help while we were there, but there was none to be had.

We had to leave, but we promised we’d do everything we could to help him.

“I love you,” I told Vasco, hugging his tiny shoulders before we had to catch a flight back home.

To make a long story short, on April 29, 2009, Vasco arrived in Chicago to have surgery that repaired his heart (and ours). In 2010, we legally and officially became Vasco’s forever family, something we’d been from the moment our eyes met.

Now Vasco, a strapping 19-year-old in perfect health, is back home in California with his dad, getting ready for final exams at the end of his first year of college classes, and I am in Idaho caring for my mother, who recently entered hospice.

I’m a little sad today.

I don’t know what the future will hold.

But thanks to Vanier, he now of blessed memory, I am certain the only path to get there is love.

(Cathleen Falsani is an award-winning, veteran religion journalist and author, specializing in the intersection of spirituality and culture. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)