(RNS) — Salman Azhar and his wife, Azleena, had been thinking of making the hajj for a while now. This year they finally received what they called “an invitation.”

As Muslims, the couple believes that when the time is right, God sends an invitation to make the physically demanding and spiritually uplifting pilgrimage to Mecca, one of the five pillars of their faith.

[ad number=“1”]

For the Azhars — he’s a visiting professor at Duke University’s computer science department and business school, she’s volunteer chaplain at Duke Hospital — that invitation, or calling from God, became apparent: They were ready, able and willing.

“My wife and I, and most Muslims, believe that one does not just ‘decide on going to hajj’ and then ‘show up,’” he said. “All those who have come for hajj are considered to be invited guests of God.”

Salman Azhar receives a haircut after spending the Eid al-Adha holiday at Muzdalifah, near Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. Photo courtesy of Salman Azhar

In public and private messages on Facebook, Salman Azhar described the pilgrimage that he and his wife are set to conclude on Sunday (Sept. 6). They spent Friday, the annual Eid al-Adha holiday, at Muzdalifah, a plain eight miles from Mecca, where they took part in the symbolic “stoning of the devil” ritual by casting pebbles at three walls. Afterward, Azhar was looking forward to getting a haircut — a sign of renewal.

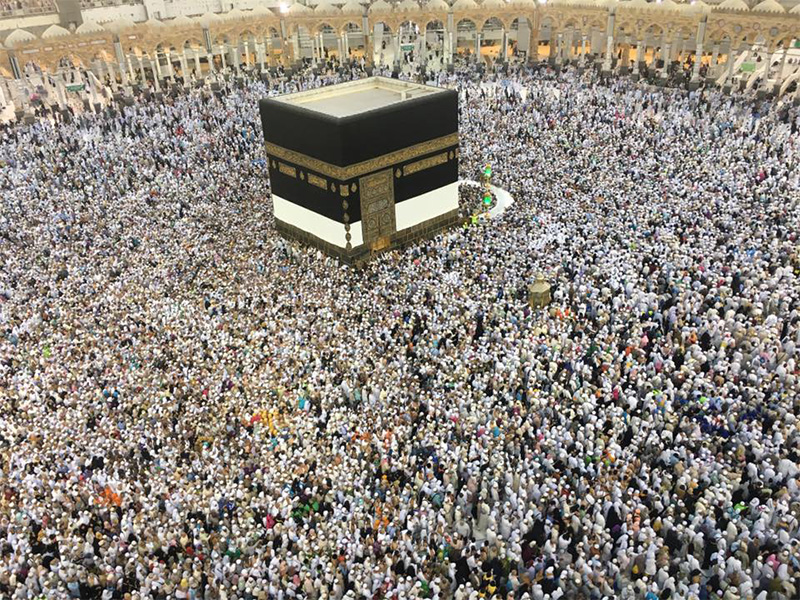

Some 2 million people from around the world gathered in Saudi Arabia this past week for the hajj, a once-in-a-lifetime rite for most Muslims in which they try to attain spiritual purification through repentance. Among them were several thousand Americans.

Azhar, 50, had gone on hajj 17 years ago but he fell sick halfway through and wanted to complete the journey alongside his wife who had never been.

[ad number=“2”]

After his mother-in-law volunteered to stay in Durham, N.C., with their two youngest boys, ages 10 and 17, Azhar began to seriously consider the journey. Their oldest son is a senior at Duke.

The timing wasn’t ideal. Classes were just starting at Duke, and he would have to find a replacement to teach the first two sessions of his undergraduate seminar, “Technical and Social Foundations of Information of the Internet.”

Salman Azhar in Saudi Arabia. Photo courtesy of Salman Azhar

But when he shared his desire to go with colleagues, they didn’t blink.

“We didn’t think for a second, other than saying, ‘What can we do to make this happen?’” said Owen Astrachan, a professor of computer science.

The couple bought a package trip that included airfare and hotel stays through a travel agency that arranges hajj pilgrimages. They attended two orientation classes to help prepare. Friends who had gone before offered useful tips.

“When we hit the road, we felt information overload,” Azhar wrote. “However, the spirit of the journey dwarfed all the mundane logistics, and we followed our hearts, and our hearts loved that.”

Once in Mecca, they found people of all nationalities speaking a multitude of languages. In a small shop, his wife hesitated trying to figure out how to communicate with a shopkeeper whereupon the shopkeeper pulled out a list of 26 languages, and asked her to pick one.

Azhar likened the experience to a “semester abroad program.”

A sign in multiple languages demonstrates the multicultural atmosphere surrounding the hajj in Mecca. Photo courtesy of Salman Azhar

“You have people from all over the world gathered here speaking hundreds of languages, with all different skin colors and diverse cultures,” he said. “You can pick what you want to learn!”

The beauty of the hajj is that Muslim cultural differences are seamlessly accommodated, he said. Everyone dresses in nearly identical white garments, meant to symbolize unity. But there’s also greater respect for difference.

One day Azhar found himself in a non-carpeted area at the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina during the morning prayers. After plopping down his prayer rug, he realized he was praying with a Shiite group because the pilgrims were standing in prayer with their hands down. Most Sunnis stand with their arms folded.

When they prostrate, Shiites touch their foreheads to a floor or some other natural area, not a rug, so Azhar folded the left corner of his prayer rug, which he was sharing with a fellow pilgrim in a gesture of deference to his tradition.

When his fellow worshipper was done, Azhar said, “He calmly straightened my rug, patted it with some love, and continued with his prayers.”

[ad number=“3”]

A harder challenge was learning self-restraint at Mecca and Medina’s lavish breakfast and dinner buffets, which were included in their hotel package.

After a bout of stomach upset, the couple decided the tempting delicacies were a major impediment to their spiritual growth and they resolved to cut down their food intake.

Though he is thankful he could afford to make the pilgrimage in comfort and ease, the entire experience reinforced for Azhar a desire to do more with less.

“I’m competitive and I got pwned (or “beaten”) by the spiritual level of people who lived an austere life to save all their lives for this journey,” he said. “I’m not even in the same league.”

On Thursday, as the pilgrims left for Mount Arafat, the spot where the Prophet Muhammad delivered his final sermon more than 1,400 years ago, Azhar found another chance to walk the talk.

Sandals are easily lost amongst the hundreds of thousands of hajj pilgrims in Saudi Arabia. Photo by Salman Azhar

As he was leaving a prayer hall where everyone prayed barefoot, he couldn’t find his flip-flops and then spied an old man in the group wearing a pair just like his.

“I gently touched him on his shoulder and asked, “Are you sure those slippers are yours?” He responded, “No, I lost mine.”

Azhar said he composed himself, took in the situation and concluded: “I haven’t had an extra credit opportunity like this, ever. I told them no problem and walked away.”

Humility, Azhar decided, is one of the key experiences here. Love and service are the others.

“I want to relieve that separation anxiety that we feel sometimes when we don’t feel God’s love and presence and when we don’t love other people with all our heart and soul,” he wrote.

“A natural side effect of this relief should be, inshallah (God willing), for us to be better human beings who love and care for others and propagate that feeling all over the world.”