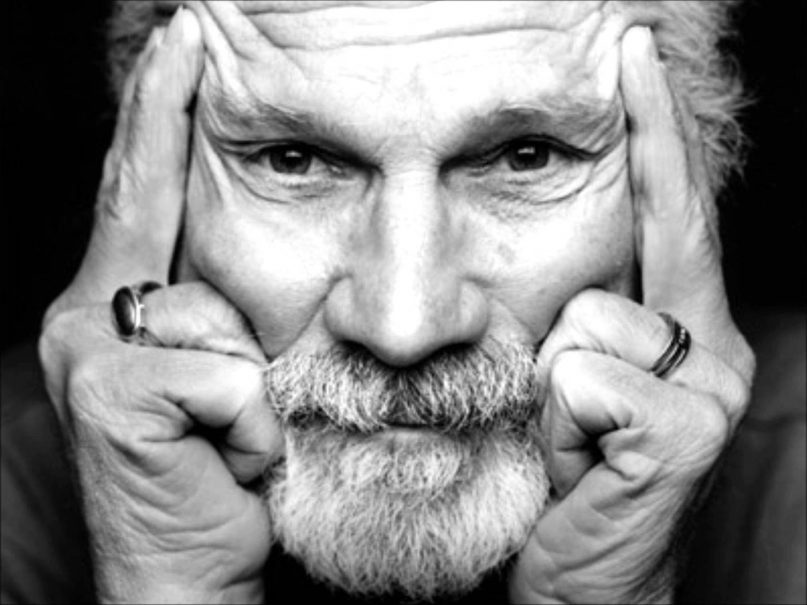

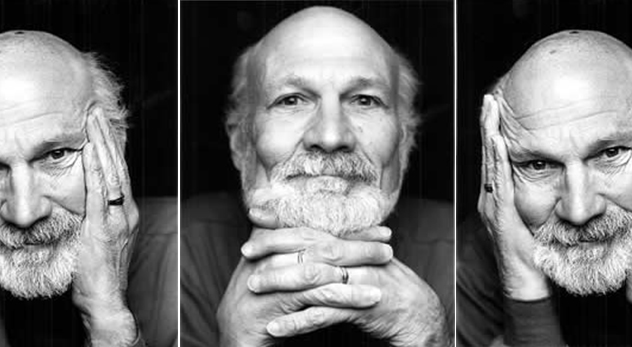

Time Magazine once called him “America’s Best Theologian.” Today, the nearly 74-year-old Christian is thinking a lot about “approaching the end.”

As his hair grays and thins, Stanley Hauerwas thinks a lot more about the end. Not just the end of his life—though he ponders that, too—but also the end times.

Once named by TIME Magazine as “America’s Best Theologian,” Stanley Hauerwas is now an accomplished 74-year-old whose words grow increasingly prophetic in tone. His book “Approaching the End: Eschatological Reflections on Church, Politics, and Life” teases out some of the ideas on which he’s been ruminating. Thinking about last things, he argues, is essential helping the church negotiate the contemporary world.

Here, we discuss his views on the end times, what he thinks of “Left Behind” theology, and how he hopes to be remembered after he dies.

RNS: The end times prophecy craze has many Christians thinking of “eschatology” as the chronological end. You affirm the time aspect, but “end” has another meaning for you, doesn’t it?

SH: Other than indicating chronology, “end” names the purpose of God’s creation found in Jesus Christ. So eschatology names a Christian presumption that there is a beginning and an end, and we have seen that end in Jesus.

RNS: The “Left Behind” books series has sold more than 60 million copies. What do you think when you hear that so many have been influenced by that brand of eschatological thought?

SH: [tweetable]My reaction to the “Left Behind” series is one of amusement and pathos.[/tweetable] Pathos because so many people have misunderstood Christian eschatological convictions and turned them into speculative accounts of the so-called “rapture.” I take it to be a judgment against the church that that kind of speculation has gained a foothold.

RNS: You argue that “we may be living during a time when we are watching Protestantism coming to an end.” Some people may look at the hundreds of millions of Protestants in the world and call you crazy. Explain.

SH: My suggestion is meant to be a reminder that Protestantism is a reformed movement. When it becomes an end in itself it becomes unintelligible to itself. [tweetable]Protestants who don’t long for Christian unity are not Protestant.[/tweetable] There is also the ongoing problem that Catholics have responded to the Protestant critique in a way that the Protestant critique no longer makes much sense. Accordingly, the question is: why do we continue to be kept apart?

RNS: How does eschatology and thinking about the future shape the way we understanding the suffering that currently swarms our lives?

SH: This is a very complex matter. The attempt to justify suffering by appealing to the future is not a form of Christian pathos. As Christians, we must hold together the truth of living in a fallen world and the suffering that attends that truth without throwing up our hands and waiting for someone else, even God, to make everything all right. That’s not Christian hope. We are called to address sin and to serve those who suffer.

At the same time, the suffering of martyrdom is also constitutive of our faith, and this must also be held onto. But that in no way means we can make martyrs out of those who are suffering when what is commanded is that we feed, clothe, and protect the least of these. When we attend to the suffering in the world we, at times, are able to catch glimpses of the in-breaking of eschatological hope. Christian hope means living into eschatological hope now, not in some distant future.

But this same hope requires that we be a people who know how to be patient and that we become a people who know how to wait upon the Lord. Waiting does not mean inaction. It means prayer and paying attention and joining the Lord in the many ways he is already redeeming the world.

RNS: You turn 74 years old this month. How has approaching your life’s end changed the way you think about the eschatological “end?”

SH: I am not sure how my drawing closer to death has changed how I think about an eschatological end. Eschatology is fundamentally a strong historic claim about a people. How participation in that people is to be expected after death is something I do not speculate about. I do assume, however, that there is some relation between who I am now and who I will be after death because I assume [tweetable]the Lord who draws me to death is the Lord who draws me into life.[/tweetable]

RNS: As you look at where the “Church” (insofar as we can speak of a single church) is headed, what most concerns you about the future? What most gives you hope?

SH: I’m quite uncertain where the church is headed. But I am sure the Lord will raise up Christians for the future in a manner that may be quite surprising. Our hope is exactly that trust in God’s work. But how I see that work happening in the West is that he’s making the church leaner and meaner.

RNS: When you pass from this life to the next, how do you hope people will remember Stanley Hauerwas?

SH: When I die, I hope people will think I’ve had a wonderful life because the Lord gave me something wonderful to do. I hope I am not remembered because I’m allegedly famous, but because I have so enjoyed what it means to worship God.