“We Shall Overcome” became the anthem of the civil rights movement in large measure because of Guy Carawan, the white singer and folklorist who died at the age of 87 a few days ago. When he sang it at the inaugural meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Raleigh, N.C. in April of 1960, he “fathered the musical manifesto that, more than any other, became ‘the “Marseillaise” of the integration movement,’ as The New York Times described it in 1963,” in the words of Times obituarist Margalit Fox.

But as Fox points out, Carawan didn’t write “We Shall Overcome” and never claimed to have. He learned it at the Highlander Research and Education Center, a social justice and cultural institute in East Tennessee where he worked as music director from 1959 until his retirement in the late 1980s.

A lot of energy has been spent tracking down the origins of the song, and the evolution of the title, structure, and lyrics is reasonably clear, right up to Pete Seeger’s changing of “will” to “shall.” As one might have expected, the text is rooted in the African-American church.

But the sources of the music lie much farther afield. The first eight measures derive from “O Sanctissima,” a hymn to the Virgin Mary that was first published in 1792 and later arranged by Beethoven. What really sells the song, however, is the phrase in measures 9-12: “Deep in my heart I do believe.” That phrase is melodically and harmonically identical to the opening bars of “Caro mio ben,” a love song by the late-18th-century Italian composer Tommaso Giordano that became part of the standard art song repertory in the 19th century.

Songs don’t compose themselves, of course. And in this case, the composer had to have been someone familiar with these classical pieces. Although no one, so far as I know, has ever said so directly, the credit must belong to Zilphia Horton, the social justice activist and musician who was Carawan’s predecessor as music director of the Highlander Center.

Horton (née Johnson) grew up in the north central Arkansas town of Paris, the eldest daughter of an affluent coal mine supervisor. She began piano lessons at the age of five and grew to be an accomplished singer, studying classical music at what is now the University of the Ozarks. She was instilled with a commitment to social justice by Rev. Claude Williams, who became pastor of Paris’ Cumberland Presbyterian Church in 1930. (The Cumberland Presbyterians were a revivalist denomination that broke with mainstream Presbyterianism in the early 19th century over the Calvinist tenet of election.)

Horton joined Williams’ campaign to unionize her father’s mine, as a result of which she was kicked out of the house and disowned. Making her way to what was then called the Highlander Folk School, she soon married Myles Horton, one of its founders. There she devoted herself to arranging music and putting it along with other arts to the service of social justice for the poor and oppressed until her untimely death in 1956 at the age of 46.

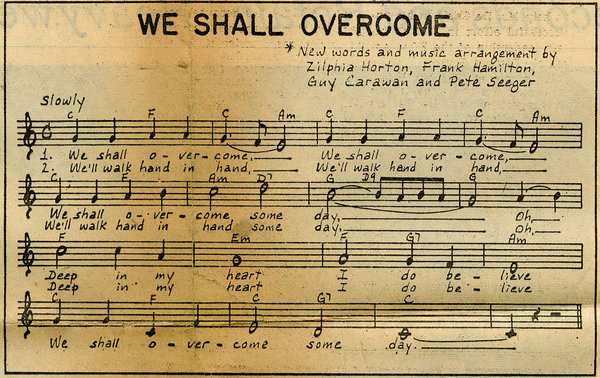

Horton was cagey about the provenance of “We Shall Overcome,” saying that it was first sung by African-American strikers in Charleston, S.C. in 1945. It was her favorite song, she sang it all the time, and taught it to Pete Seeger. An early printed version attributes the authorship this way: “New words and music arrangement by Zilphia Horton, Frank Hamilton, Guy Carawan and Pete Seeger.”

The ideology of folk songs is such that they are supposed to emerge from “the folk” rather than from the cultural elite, and in part “We Shall Overcome” did. But there is little question that its musical setting came by way of the refined classical training of the coal mine superintendent’s daughter.