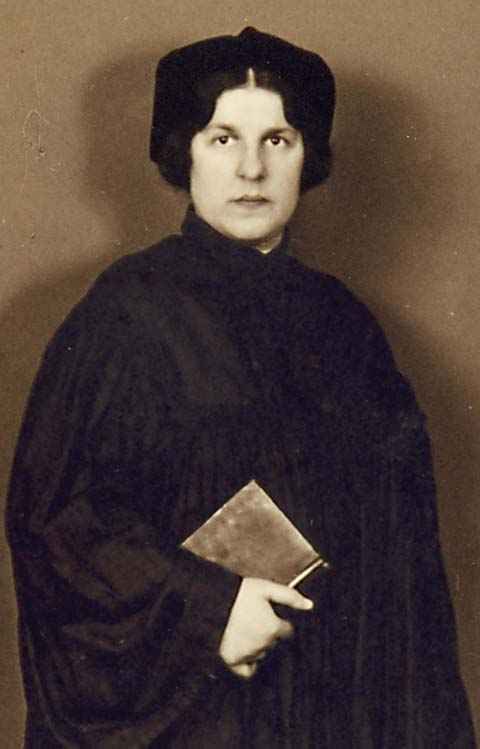

The first woman rabbi was a German Jewish woman named Regina Jonas. For too many years, her story has been lost.

(RNS) Who was the first woman rabbi?

Sally Priesand, ordained as a Reform rabbi in 1972, right?

Wrong.

It was a German Jewish woman named Regina Jonas. For too many years, her story has been lost.

No longer. Next month there will be a conference in Potsdam, Germany, sponsored by the Abraham Geiger College (Germany’s first rabbinical seminary since the end of World War II), commemorating her legacy and the role of women in religious leadership.

And why remember her now?

Because December marks the 80th anniversary of her ordination.

And because her memory had been hidden for so long.

READ: Kerry to Netanyahu: Time for all to end inflammatory rhetoric

Jonas was born on Aug. 3, 1902, in Berlin. At the age of 21, she began teaching in an Orthodox Jewish school.

She enrolled in the Hochschule fur die Wissenschaft des Judentums, the seminary for liberal rabbis and educators. There, she attained the qualification of “Academic Teacher of Religion.”

But Jonas wanted to be ordained as a rabbi. To that end, she wrote a thesis: “Can a Woman Be a Rabbi According to Halachic Sources?”

Her conclusion, based on biblical, Talmudic and rabbinic sources, was an unqualified “yes.”

Most of her professors supported her. But the esteemed Talmud professor Chanoch Albeck flatly stated: “I do not ordain a girl.”

Jonas then turned to Rabbi Leo Baeck, the spiritual leader of German Jewry.

Baeck greatly respected her, but he refused to ordain her. He sensed what lay ahead for the Jewish community of Germany, and he did not want to compromise communal unity.

Ultimately, Jonas turned to Rabbi Max Dienemann, a distinguished liberal rabbi in Offenbach. On Dec. 27, 1935, he ordained her as a “rabbi in Israel.” Six years later, on Feb. 6, 1942, Baeck himself signed a certificate confirming her ordination as well.

Rabbi Jonas found work as a chaplain in various Jewish homes for the aged and the orphaned.

And then, Kristallnacht — November, 1938. The Nazis sent many liberal rabbis to concentration camps. Others were able to flee. Jonas was left behind, and because there was a shortage of rabbis, she was finally able to function as a rabbi.

READ: Controversial study: Many Conservative rabbis open to officiating at intermarriage

How ironic: The Nazi onslaught destroyed countless rabbinates. And it created a rabbinate, as well.

Jonas was ordered into forced labor in a factory. And yet, she continued her pastoral work, teaching and preaching.

One survivor remembers: “Whenever she preached to those who were to perform forced labor, they filled the place to capacity. Those who did not manage to get in stood in the doorways as far as the street.”

On Nov. 3, 1942, Jonas was forced to fill out a declaration form by the Nazis. That declaration form listed her property — including all her books. Two days later, all her property was confiscated “for the benefit of the German Reich.”

The next day, she was arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Even there, her rabbinate did not end.

In fact, her partner in pastoral psychology was the well-known psychologist Viktor Frankl. Her job was to meet the transports at the railway station. There she would help people deal with their sense of shock and disorientation.

Frankl wrote a great deal about his experiences during the war. His work with human beings in the camps served as the centerpiece of his philosophy and the subject of his masterpiece, “Man’s Search for Meaning.”

And yet, Frankl never mentioned Jonas in his writings. Neither did Baeck.

It took Frankl 50 years to remember her.

In 1991, the German-American theologian Katharina von Kellenbach asked Frankl directly about Jonas. He admitted he remembered her as an energetic woman, with an impressive and powerful personality.

He was even able to recite one of her sermons from memory.

This is a section from one of Jonas’ sermons in Theresienstadt:

“Our Jewish people is sent from God into history as ‘blessed.’ This means that wherever one steps in every life situation, bestow blessing, goodness and faithfulness — humility before God’s selflessness, whose devotion-full love for his creatures maintains the world.”

For two years, Jonas worked tirelessly in Theresienstadt. Finally, she was deported to Auschwitz. Her exact date of death is not clear; sometime in late 1944.

She was 42 years old.

READ: Bibi, be careful with Holocaust history

And now, the even deeper tragedy.

Go back to the Hochschule in Berlin.

In 1932, there were 155 students.

Twenty-seven of them were women.

Rabbi Jeffrey Salkin is the spiritual leader of Temple Solel in Hollywood, Fla., and the author of numerous books on Jewish spirituality. Religion News Service photo by Steve Remich

Their names have disappeared. True, they were studying to become teachers. But, like Jonas, might they have become rabbis?

We weep for the lives that were lost.

We weep for the teaching and wisdom that was lost, as well.

How do we best honor Regina Jonas’ memory?

By making sure that no woman’s spiritual gifts will ever be forgotten again.

(Rabbi Jeffrey K. Salkin is the spiritual leader of Temple Solel in Hollywood, Fla., and the author of numerous books on Jewish spirituality and ethics, published by Jewish Lights Publishing and Jewish Publication Society.)

YS/MG END SALKIN