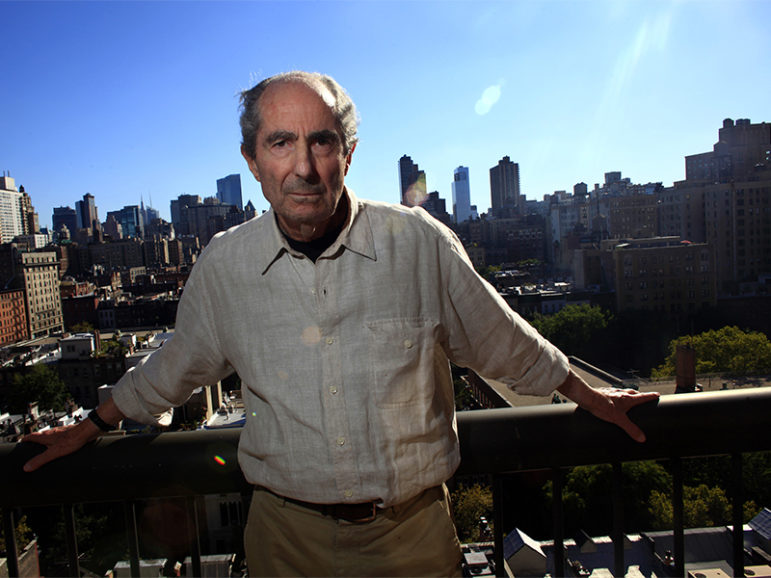

Author Philip Roth poses in New York City on Sept. 15, 2010. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Eric Thayer

(RNS) Philip Roth, my pick as America’s greatest living author, publicly announced three years ago at age 80 that he would do no more writing. That’s a shame because the Newark, N.J.-born Roth is today more popular than ever. Indeed, two of his many superb novels — “Indignation” and the Pulitzer Prize-winning “American Pastoral”– are critically acclaimed 2016 films.

The first book, set in the early 1950s, depicts a small Midwestern college’s stifling and hostile anti-Semitic atmosphere that confronts a Jewish freshman from Newark. He leaves the school, is drafted into the Army and is ultimately killed in combat during the Korean War.

“American Pastoral” is the 1960s story of another Newark Jewish young man; this one assimilates into wealthy upper-class New Jersey Christian society through intermarriage. However, his daughter, in an act of parental defiance and hatred of her family’s lofty socio-economic status, becomes a domestic terrorist who goes into years of hiding after participating in a deadly bombing.

And then there is the eerily prescient “The Plot Against America” (2004), also set in Newark. Roth’s novel describes how the renowned aviator Charles Lindbergh, a populist American fascist who admires Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, is elected U.S. president in 1940 instead of Franklin Roosevelt and embarks on an obscene public anti-Semitic campaign.

Many of Roth’s novels and short stories are saturated with Jewish themes and central characters. Like many other gifted novelists, he has mined his childhood experiences and written, again and again, about the people, events and issues he knows well. Roth is akin to a literary archaeologist who digs deep into his imagination and brings up youthful remembrances of things past to re-create the American Jewish milieu of his youth.

He is perhaps best remembered as the creator of the satirical takedown of vapid middle-class Jewish life in “Goodbye, Columbus” (1959) and “Portnoy’s Complaint” (1969), a semi-autobiographical exploration of a Jewish young man’s sexual hang-ups, especially his libidinous attraction to white Anglo-Saxon Protestant blond women.

When they were first published, both “Goodbye Columbus” and “Portnoy’s Complaint” sparked a firestorm of vitriolic criticism from many Jewish leaders that included a barrage of anti-Roth rabbinic sermons. Forty-five years ago Roth’s accusers charged that many of the novelist’s characters were shallow and “self-loathing” Jews who provided anti-Semites with confirmation and validation for their hatred of Jews and Judaism. One rabbi asked the Anti-Defamation League: “What is being done to silence this man? Medieval Jews would have known what to do with him.”

In 1972 Irving Howe, a widely respected author and social critic, offered a more nuanced view: “’Portnoy’s Complaint’ is not, as enraged critics have charged, an anti-Semitic book, though it contains plenty of contempt for Jewish life.”

When attacked for his writings, Roth engaged many of his critics in various opinion journals and literary magazines. However, in time the fierce attacks ebbed, and through it all, Roth continued to publish over 30 elegantly written, beautifully crafted novels. Fifty years after “Goodbye Columbus,” his first masterpiece, Roth capped his career with another, “Nemesis.” It is the heartbreaking account of the 1944 polio epidemic in his native Newark. Few novelists have exhibited such literary stamina and sustained creative excellence for such a long period.

In 2014, Roth’s steep fall and gradual rise within the American Jewish community culminated when he received an honorary degree from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City, the flagship seminary of Conservative Judaism. Arnold Eisen, the school’s chancellor, said of Roth: “His questions about Jewish life and identity and their dilemmas have always been the right questions, even if I haven’t always agreed with his answers. The outrage that greeted his early work belongs to another era, and so does his sense of being a pariah.”

Roth said how proud his deceased father would have been to see him receive the honorary degree: “I welcomed the honor. Who takes Jews more seriously than the JTS, and what writer takes Jews more seriously than I do?” He quipped: “I have not been embraced by a gathering like this since March of 1946, when my family and friends were assembled to celebrate my bar mitzvah.”

It was as if the prodigal son had, after decades of estrangement, finally “come home” to the Jewish community. But I believe Roth never really left the Jewish Newark of his youth. He was and is always “at home.”

Philip Roth and his Jewish people

(RNS) Philip Roth has not 'come home' to the Jewish community. He never really left, writes Rabbi A. James Rudin.

Author Philip Roth poses in New York City on Sept. 15, 2010. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Eric Thayer

(RNS) Philip Roth, my pick as America’s greatest living author, publicly announced three years ago at age 80 that he would do no more writing. That’s a shame because the Newark, N.J.-born Roth is today more popular than ever. Indeed, two of his many superb novels — “Indignation” and the Pulitzer Prize-winning “American Pastoral”– are critically acclaimed 2016 films.

The first book, set in the early 1950s, depicts a small Midwestern college’s stifling and hostile anti-Semitic atmosphere that confronts a Jewish freshman from Newark. He leaves the school, is drafted into the Army and is ultimately killed in combat during the Korean War.

“American Pastoral” is the 1960s story of another Newark Jewish young man; this one assimilates into wealthy upper-class New Jersey Christian society through intermarriage. However, his daughter, in an act of parental defiance and hatred of her family’s lofty socio-economic status, becomes a domestic terrorist who goes into years of hiding after participating in a deadly bombing.

And then there is the eerily prescient “The Plot Against America” (2004), also set in Newark. Roth’s novel describes how the renowned aviator Charles Lindbergh, a populist American fascist who admires Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, is elected U.S. president in 1940 instead of Franklin Roosevelt and embarks on an obscene public anti-Semitic campaign.

Many of Roth’s novels and short stories are saturated with Jewish themes and central characters. Like many other gifted novelists, he has mined his childhood experiences and written, again and again, about the people, events and issues he knows well. Roth is akin to a literary archaeologist who digs deep into his imagination and brings up youthful remembrances of things past to re-create the American Jewish milieu of his youth.

He is perhaps best remembered as the creator of the satirical takedown of vapid middle-class Jewish life in “Goodbye, Columbus” (1959) and “Portnoy’s Complaint” (1969), a semi-autobiographical exploration of a Jewish young man’s sexual hang-ups, especially his libidinous attraction to white Anglo-Saxon Protestant blond women.

When they were first published, both “Goodbye Columbus” and “Portnoy’s Complaint” sparked a firestorm of vitriolic criticism from many Jewish leaders that included a barrage of anti-Roth rabbinic sermons. Forty-five years ago Roth’s accusers charged that many of the novelist’s characters were shallow and “self-loathing” Jews who provided anti-Semites with confirmation and validation for their hatred of Jews and Judaism. One rabbi asked the Anti-Defamation League: “What is being done to silence this man? Medieval Jews would have known what to do with him.”

In 1972 Irving Howe, a widely respected author and social critic, offered a more nuanced view: “’Portnoy’s Complaint’ is not, as enraged critics have charged, an anti-Semitic book, though it contains plenty of contempt for Jewish life.”

When attacked for his writings, Roth engaged many of his critics in various opinion journals and literary magazines. However, in time the fierce attacks ebbed, and through it all, Roth continued to publish over 30 elegantly written, beautifully crafted novels. Fifty years after “Goodbye Columbus,” his first masterpiece, Roth capped his career with another, “Nemesis.” It is the heartbreaking account of the 1944 polio epidemic in his native Newark. Few novelists have exhibited such literary stamina and sustained creative excellence for such a long period.

In 2014, Roth’s steep fall and gradual rise within the American Jewish community culminated when he received an honorary degree from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City, the flagship seminary of Conservative Judaism. Arnold Eisen, the school’s chancellor, said of Roth: “His questions about Jewish life and identity and their dilemmas have always been the right questions, even if I haven’t always agreed with his answers. The outrage that greeted his early work belongs to another era, and so does his sense of being a pariah.”

Roth said how proud his deceased father would have been to see him receive the honorary degree: “I welcomed the honor. Who takes Jews more seriously than the JTS, and what writer takes Jews more seriously than I do?” He quipped: “I have not been embraced by a gathering like this since March of 1946, when my family and friends were assembled to celebrate my bar mitzvah.”

It was as if the prodigal son had, after decades of estrangement, finally “come home” to the Jewish community. But I believe Roth never really left the Jewish Newark of his youth. He was and is always “at home.”

Donate to Support Independent Journalism!