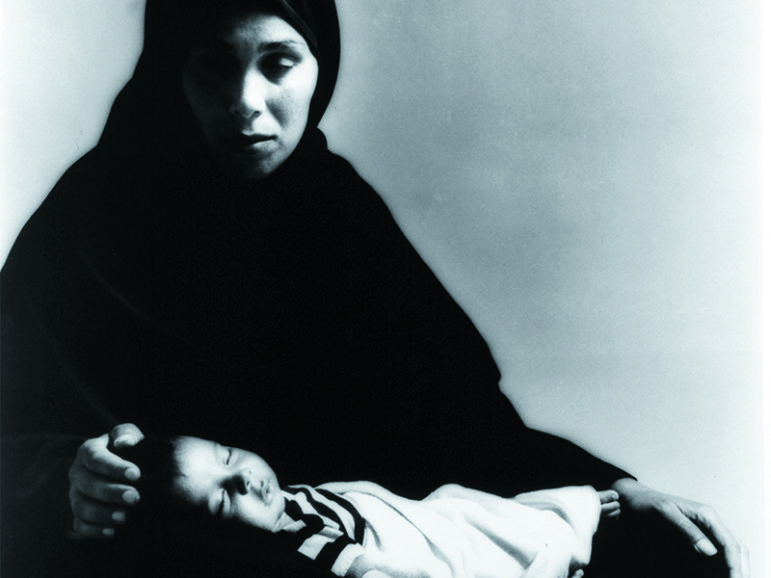

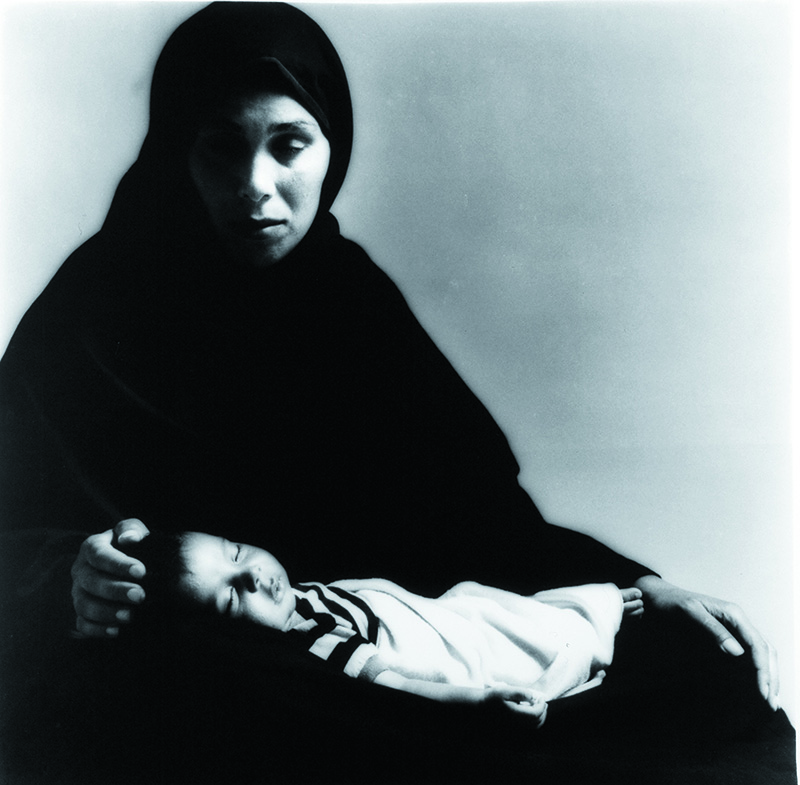

Micha Kirshner’s “Aisha el-Kord, Khan Younis Refugee Camp,” a 1988, gelatin silver print, reminds many of the Christian pieta. Image courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

JERUSALEM (RNS) At the center of the Israel Museum’s blockbuster exhibit “Behold the Man: Jesus in Israeli Art” is a life-size photograph of a woman draped in black caressing the head of a small baby asleep on her lap.

Micha Kirshner’s 1988 image “Aisha El-Kord, Khan Younis Refugee Camp” may evoke the politics of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but it just as powerfully conjures the pietà, or the Roman Catholic tradition of painting and sculpture in which the Virgin Mary holds the dead body of Jesus on her lap or in her arms.

[ad number=“1”]

“That’s the genius of the Catholic Church,” Kirshner marveled recently, “in adopting universal symbols like a mother cradling a suffering child and making them its own.”

But while the photo may be a reference to the pictorial Christian tradition, Kirshner himself is Jewish.

Capturing that image was “a spontaneous decision,” he said, arising from his desire to convey the struggles of a mother in a Palestinian refugee camp and perhaps of his own personal history (Kirshner was born in an Italian refugee camp as his parents awaited permission to travel to Israel back in 1947).

[ad number=“2”]

“People see in it the Palestinian pietà,” he said. “I imagine there is a Jewish pietà, a Buddhist pietà, and if Michaelangelo is who I think he is, it wouldn’t have bothered him that non-Christians saw themselves in his pietà.”

Kirshner’s photo and the 150 other works alongside it represent what may be the first exhibit devoted to exploring Jewish artists’ complex relationship with Christian symbols. But while these artists’ works comment on Christianity via its own symbols, they don’t emerge from a Christian faith. Instead, the artists insist they are appropriating universal symbols from the world’s largest faith and its charismatic icon, Jesus.

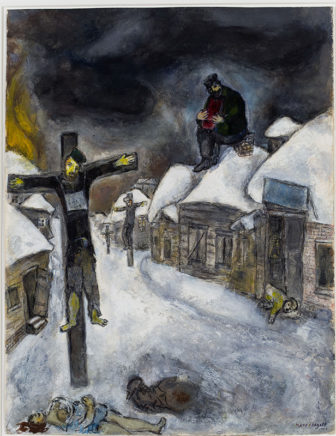

Marc Chagall, born Russia, active Russia, France and the U.S., 1887-1985. “The Crucified,” 1944. Gouache and graphite on paper, 62.2×47 cm. Image courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The exhibit opens with a few examples of 19th-century depictions of Jesus by European Jewish artists. Without exception these works were meant for gentile eyes and they plead for the humanity of Europe’s beleaguered Jews.

Marc Chagall’s “Yellow Crucifixion,” painted at the height of World War II, is a case in point. Jesus hovers in an uncertain sky bathed in yellow light — possibly a reference to the yellow Stars of David that Jews were forced to wear under Nazi rule — next to a Torah, in bright green.

Left unanswered is whether Christians who saw this and other images more felt humanity’s tug at the reminder that Jesus was a Jew, or whether they felt affronted by the suggestion.

“I found it significant to note how much Jewish artists think with Jesus,” notes Marcie Lenk, the director of Christian leadership programs at Jerusalem’s Shalom Hartman Institute. “Particularly in Israel, Christianity is often felt by Jews to be very far away and even insignificant. Yet what this exhibit shows is how deeply affected we are by some of the profound ideas and symbols of Christianity. We see here how relevant these symbols and these ideas are for Jewish artists.”

The show, curated by Amitai Mendelsohn, the head of the museum’s department of Israeli art, makes a powerful argument for Israeli artists as a native part of the canon of Western art. But it also subverts the idea that Christian art is a tool of religious devotion.

Adi Nes’ untitled chromogenic print of Israeli soldiers is suggestive of Michelangelo’s Last Supper. Image courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

As Mendelsohn pointed out, allusions to Jesus in this show are unlikely to spring from a religious impulse, and, in fact, they may not even relate to Christianity.

To the contrary, he added; if Christian symbols are central to Western art, they are by necessity also central to Israeli art.

[ad number=“3”]

“The question is complex because Jesus was a Jew,” Mendelsohn said. “A Jew from here. The symbol of Christianity is not Apollo or Zeus or any gods distant to Judaism, but a Jew.”

But, he conceded, the gaze of a Jew or of an Israeli on the figure of Jesus is different. For one, religious Jews, and many other Israelis, still associate Christianity with anti-Semitism. “They have a fear of paganism or of cruelty,” he said. Yet the Israeli gaze upon Jesus is intriguing.

“Today it’s not the gaze of fear like you saw in the past, when there was anti-Semitism,” he said. “The idea of the exhibit is to arouse curiosity. If a Christian deals with Christianity, it’s no big deal. But when a Jew does, it’s fascinating.”

Sigalit Landau, “Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea,” 2005. Image courtesy of Sigalit Landau

The exhibit, on view until April 22, closes on what appears to be an incongruous note. A video of a nude woman floating in bluish-green waters is seen from below. The woman perches on a floating watermelon the shape of a heavily pregnant belly, her arms stretched out like Jesus on the cross, her toes painted Dior red.

The entrancing work by Sigalit Landau is titled “Standing on a Watermelon in the Dead Sea.”

Landau considers the subject of the suffering artist, specifically the suffering female artist, “the image of the artist in the 20th century.”

She is also powerfully influenced by motherhood and the Judean desert — both of which come together in the figure of Mary, the mother of Jesus.

“I’m almost crucified on the watermelon,” she said of the video self-portrait, made when she was 35 years old. “It is clear I am Maria. If women are mothers and men are the Son of God, it becomes very obvious that this is a story about men.”

Landau’s video is part of a video series of burst or broken watermelons, “wounded watermelons,” in the words of Landau, who compared them to “the wounds on the body of Christ.”

But in the clip for this show, the watermelon is perfectly intact.

(Noga Tarnopolsky is a correspondent living in Jerusalem)