(RNS) “Do we really need another movie about the Holocaust?” a friend asked.

Apparently, we do — and not simply to remind us of unfathomable evil, but also of unfathomable good.

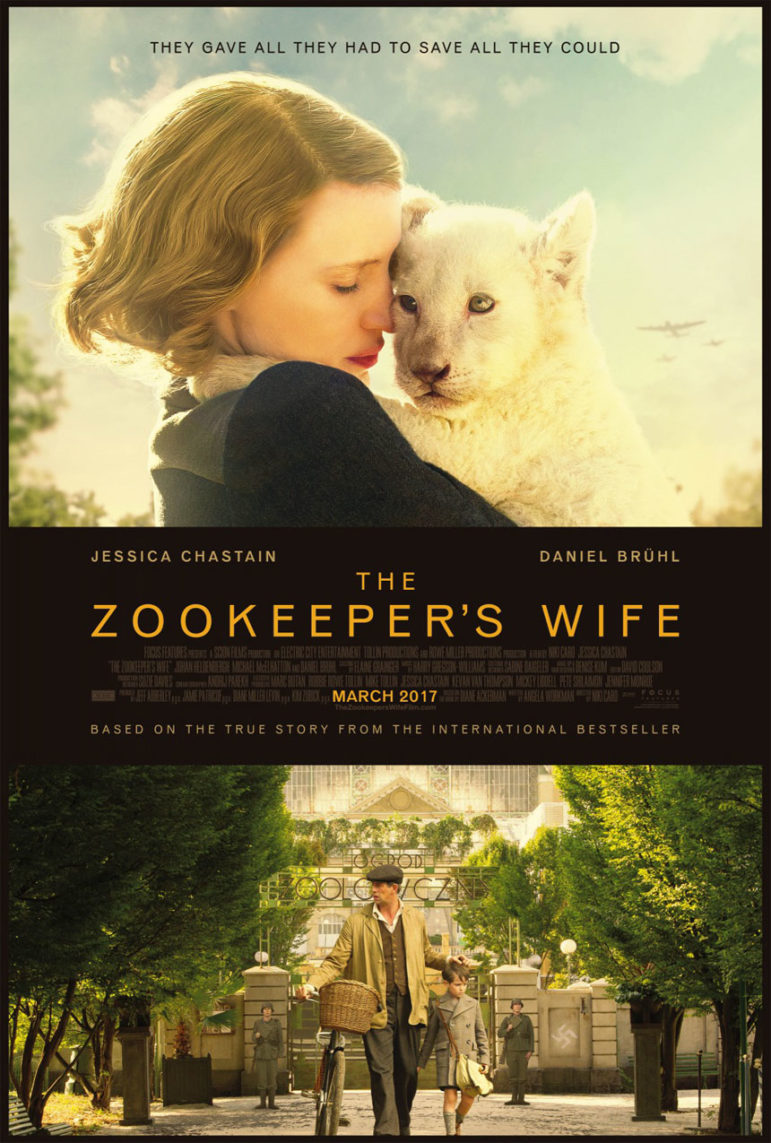

That is my take on the new film, “The Zookeeper’s Wife.”

It is the story of Jan and Antonina Zabinski, who ran the zoo in Warsaw, and who turned the zoo into a secret refuge for Jews in Warsaw during the Holocaust.

A cynic might say that the film is “Dr. Doolittle” meets “Schindler’s List.” But that diminishes the power of the film.

At the beginning, we see Antonina Zabinski risking her life to save an elephant.

As the plot develops, however, we see her risking her life — not to save animals, but to save human beings.

It reminds us that not everyone in those dark years demonstrated the same moral priorities.

The Allied forces, for example, made massive efforts to rescue the prized Lipizzaner stallions.

But as for making efforts to save Jewish children, made in God’s image — not so much.

The Zabinskis succeeded in saving three hundred lives. They were honored by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

They were far from alone, and certainly not among the Poles. Yad Vashem has identified more Poles as Righteous Among the Nations than any other nationality.

There were far fewer righteous gentiles than we needed. No more than five to ten percent of the Jews who survived the Shoah did so because of someone’s heroism.

But there were also far more righteous gentiles than we had thought.

That is why we must tell their stories — including several stories that have lately appeared in the news.

First, the story of Prince Charles’ late grandmother, Prince Philip’s mother — Princess Alice of Battenberg.

Princess Alice grew up in Germany, England, and the Mediterranean. After marrying Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark in 1903, she lived in Greece until the exile of most of the Greek royal family in 1917.

During World War Two, Prince Alice remained in Greece. There, she sheltered Jewish refugees. She founded a Greek Orthodox order. As a result of her heroism, Yad Vashem recognized her as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations.”

Princess Alice died in 1969. She had wanted to be buried in Jerusalem. In 1988, her body was transferred to the crypt at the Convent of Saint Mary Magdalene in Gethsemane, on Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives.

When Prince Charles was in Jerusalem for Shimon Peres’ funeral, he made a side trip to visit his grandmother’s grave.

And recently, when he was visiting Austria with Tony Blair, Prince Charles spoke to a group of Holocaust survivors about his grandmother, and the moral legacy that she had left to him.

Second, Masha Leon, the society columnist for the Forward, who died last week at the age of 86.

Masha Leon was born in Warsaw, before the creation of the ghetto. She almost died.

How did she survive?

A Roman Catholic woman hid her and her mother for three days.

And why did this woman do this? The woman told her that she was paying them back — because, during World War One a stranger had saved her life.

That is called the contagion of goodness (or, if you prefer, when virtue goes viral).

Why should we tell these stories during Passover?

It is because of my third story.

It is the story of Pharaoh’s daughter. The Bible does not give her a name, but the ancient rabbis knew her as Bityah.

Bityah saw the infant Moses, floating down the Nile, and the biblical text says that she actually heard his cries.

His cries were so loud that they were not only audible; they were actually visible.

Why was he crying so loudly?

Rabbi Tzvi Yechezkel Michaelson was one of Warsaw’s most revered rabbis.

This is what he taught: at that moment, it wasn’t just Moses that was crying.

Moses’ cries contained the cries of all Jews, all Jewish children, across eternity.

Rabbi Michaelson knew the cries of Jewish children. He had heard so many of them.

Rabbi Michaelson died in Treblinka in 1942. No doubt he heard those cries until his dying day.

What finally happened to Bityah?

A medieval midrash reminds us that the final plague that befell Egypt was the death of the first born.

That should have included Bityah.

At that moment, Bityah confronts her son: “Is this how you repay me?” she asks.

Moses prayed to God. Because she saved Moses’ life, God spares her life as well, and she left Egypt with the Israelites.

There is a prayer that appears at toward the end of the Passover Seder which calls down curses upon the enemies of the Jews: “Pour out Your fury on the nations that do not know you … for they have devoured Jacob and destroyed his home.”

This text is an understandable response to the persecutions of Jews in the time of the Crusades.

But, our tradition has made room for a counter-prayer as well — a prayer for righteous gentiles.

“Pour out Your love on the nations who have known You … for they show kindness to the seed of Jacob and they defend your people Israel from those who would devour them alive.”

This is not a modern “kumbaya” text.

It first appears in a Haggadah published in Worms, Germany, in the late 16th century.

You can listen to a wonderful rendering of that prayer here.

And when you hear that prayer, you will think of Princess Alice, and the woman who saved Masha Leon, and the other righteous gentiles — Christians, Muslims and atheists — who saved Jewish lives.

And you will give thanks for the spirit of Bityah, that potentially lives within every person.