(RNS) — The past few years have seen several high-profile debates about the word “Islamophobia.” Can someone be phobic about a religion the way they can have a phobia of a race or ethnicity? Is it just a buzzword that gets thrown at anyone and anything critical of Islam and Muslims?

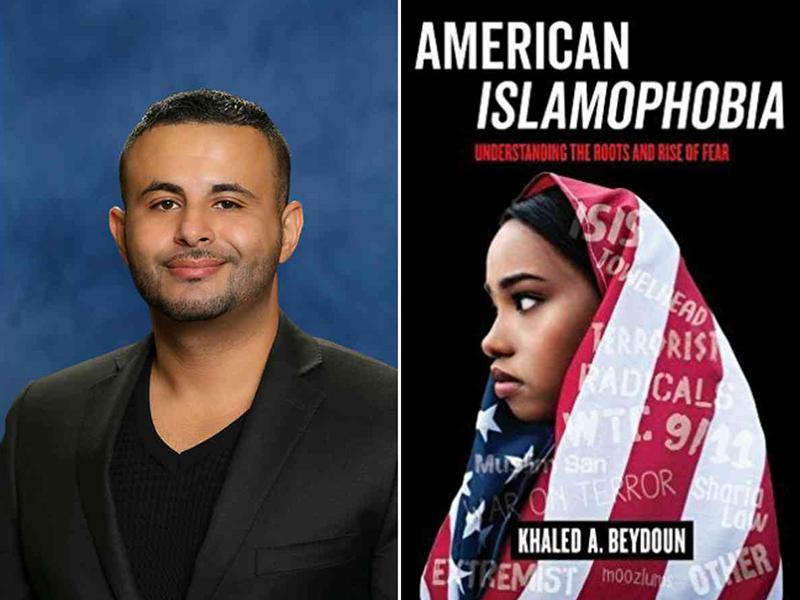

“American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear” by Khaled Beydoun. Image courtesy of UC Press

“There’s no controlling definition of Islamophobia,” said Khaled Beydoun, an associate law professor at the University of Detroit Mercy School of Law. “So that leads to the idea that there’s a disjointed understanding of it in the popular sphere.”

In his new book “American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear,” Beydoun develops a framework for grasping the phenomenon.

His work is one of the first scholarly examinations of Islamophobia’s ties to American law, policy and profiling by the state. Beydoun, who also works with the Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project at the University of California, Berkeley, draws on his scholarship as a lawyer and critical race theorist to document the institutionalization of Islamophobia in the U.S., from the antebellum South, when Muslims from Africa were among those enslaved, to the post-Muslim ban era.

His conclusion? Islamophobia is complex, multifaceted and deeply embedded in American history and law.

Beydoun spoke to Religion News Service about Islamophobia’s roots in “Orientalism” — the theory that Europeans historically viewed Middle Easterners as backward and uncivilized — and anti-blackness, the Islamophobia of the political left and the controversial scene involving the rescue of girls kidnapped by Boko Haram in the film “Black Panther.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Some critics, such as author Sam Harris, say the term Islamophobia is invalid and meaningless. But you run with it in your book. Why did you choose to stick with the word?

I’m less concerned with the absolute term itself and more with what it, as an instrument, enables scholars and advocates to do. The term isn’t perfect, but neither are words like homophobia, transphobia, anti-Semitism, even racism. There’s much debate as to whether those words are effective as well. For me, it’s just a label I use as an expedient.

Around 2007, the word started catching a lot of resonance, particularly surrounding public outcry around the Ground Zero mosque and the emergence of anti-Sharia legislation during the height of the Tea Party movement. That’s when the word started gaining popular purchase, which of course skyrockets during the rise of Trump because of the rhetoric he engaged in.

There are legitimate scholarly critiques of the word, and some of them I actually agree with. But Sam Harris is an Islamophobe and not a scholar. His arguments are coming from a place of considerable bias and venom. So a critique from him doesn’t hold much weight with me.

In your own definition of Islamophobia, you discuss personal prejudices and vigilante violence as well as the codified, state-enforced policies and programs that contribute to the othering of Muslims. Can you explain the interplay between the two?

The third dimension of my definition is what I call dialectical Islamophobia. You have private Islamophobia by individuals and citizens, and then there is structural, or state-sponsored, Islamophobia. Dialectical is the process whereby the law, policing policies and programs, effectively endorse the ideas that there’s a correlation between Muslim identity and terrorism. By virtue of the law being built upon that baseline, it’s essentially authorizing the popularly held stereotypes by private individuals — Muslims are tied to radicalization, terrorism, subversiveness.

The state-sponsored policy effectively endorses those stereotypes, and during times of crisis it might embolden violence in private individuals. The U.S. government is really rubber-stamping that anger and backlash. So they’re tightly linked in that way.

Discussions of the Muslim-American experience often focus on Arab identity. You instead look at Islamophobia’s roots in anti-blackness. Why?

The Muslim-American narrative is tied to the construction of whiteness, which in turn is heavily reliant on anti-black racism in the sense that white identity was constructed to be the opposite. For a long time in this country, whiteness was a prerequisite for citizenship. When non-black Muslims came from abroad, they had to demonstrate that they were in fact white to become naturalized citizens.

So the Muslim-American experience is rooted in the black experience, because the first Muslim communities in this country were in fact black. There were enslaved populations in the antebellum South, largely, who practiced Islam and tried to persevere in their faith against persecution by slave masters and against the letter of the law. And these communities have been erased and forgotten in our history. And today, as well, we forget that three of the seven Muslim-majority countries listed on the Muslim ban are in Africa.

What do many young activists working against Islamophobia today not understand about Islamophobia?

Did you watch “Black Panther”? Before I saw the movie, I read some articles and Facebook posts that were calling the film Islamophobic (for a scene in which the main characters save a group of kidnapped Chibok girls from Boko Haram). And when I saw the movie, I was like, yes, there are some concerning elements. Why are they including Boko Haram in the movie when the group isn’t central to the plot? And I was uncomfortable with that scene being so early in the movie — it forces people to think about Islam in criminal or villainous terms throughout the rest of the film.

Author Khaled Beydoun. Photo courtesy of UC Press

But when I read the many criticisms of that scene from millennial activists, it showed me that there isn’t a real strong understanding of what Islamophobia actually means. Without a uniform consensus on a definition, people can make the indictment of Islamophobia against anything. So “Black Panther,” was indicted as Islamophobic because of a scene that some deemed to be problematic.

I want this book to show people that Islamophobia is complex. It’s blatant in the form we saw when three Muslim students were killed a few years ago in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. It’s hidden in the way that counter-radicalization policies work in our most vulnerable communities. It’s unleashed by the biggest bigots coming from the right, but it’s also endorsed by individuals that we qualify as liberals and progressive allies. It’s a system and a dialectic that ties the action of the state to the actions of private people. That’s what I want young people to understand.

You’re not shy in pointing out Islamophobia among liberals. But many of your readers might expect to see Donald Trump’s presidency act as a foil to Barack Obama’s administration in terms of relations with Muslims. Why do many people, Muslims included, have trouble spotting liberal Islamophobia?

President Obama is pegged as a progressive president, and he engaged in rhetoric toward Muslims that might be seen as accepting or tolerant, but let’s not lose sight of the policies. He launched “Countering Violent Extremism” policing in 2011, which turned Muslim Americans against one another, and he expanded the surveillance state beyond the measure of the Bush administration. He flew drones in Yemen and other parts of the Arab world.

People of color were smitten by the kind of rhetoric Obama was engaged in. He went to Cairo in 2009; he gave a really beautiful speech about mending the wounds between the U.S. and the Muslim world. People loved that. In many ways, his words were unprecedented for a U.S. president. This was coming right after the Bush administration, which embraced “clash of the civilizations” rhetoric. It was viewed as a new day for Muslims, a watershed moment.

Seven years later in Baltimore, when he made his first visit to a U.S. mosque, it was really just a failed pitch for counter-radicalization policing. Throughout his presidency, his engagement of Muslims was done to advance counter-radicalization. You also see that with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. She never mentioned Muslims outside the context of the “war on terror.”

If people take issue with calling that Islamophobia, then they have a very flattened and narrow understanding of the term. Many people can agree that (HBO talk show host) Bill Maher is an Islamophobe, and I think they can agree that he’s a libertarian or a progressive. If a liberal pundit can engage in Islamophobic rhetoric on TV, then why can’t a liberal politician in the White House?

Your description of structural Islamophobia makes it seem impossible to defeat. So what gives you hope in your fight?

I don’t think Islamophobia can be vanquished, but it can be diminished. We’re dealing with centuries upon centuries of destructive histories, ideas and epistemologies against Islam and Muslims that can’t be defeated overnight. These Orientalist tropes that Muslim men are menacing, brooding, that Islam as a religion is a political ideology committed to decimating the West, that Muslim women are subordinate and disempowered — these stereotypes are not new. They’re reified in law. They’re perpetuated by media and on film. So we’re not going to defeat them. But I think we can curb them.

The most important thing for Muslims is that we have individual Muslims occupying spaces of power now. We have the agency and the empathy to develop stories about our religion and our people that can help erode demonization of our faith. We have a mounting generation of leaders in various sectors who can do that more successfully than ever. I see that as a big step.