In our minds, he is frozen at the age of 39 years old. Our souls gasp in wonder at all he did, all he was, all he would come to embody – at an age that many of us would still view as tender.

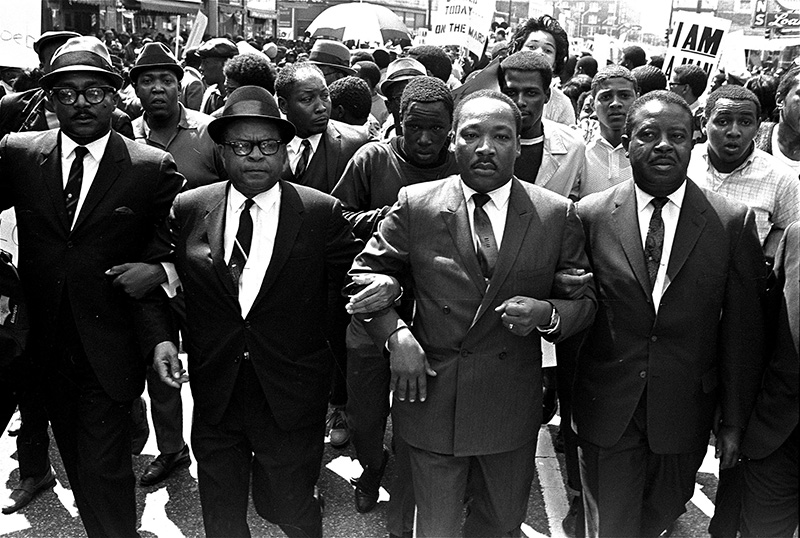

Fifty years ago, The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Memphis, Tennessee on a unique mission.

It was, only in a narrow and nuanced sense, a mission of civil rights.

Dr. King understood intersectionality: between the rights of black people, and the rights of workers, and the rights of poor people – and especially, the rights of poor, black, working people, especially the sanitation workers, who were striking after years of mistreatment and poor wages, and for whom Dr. King had come to Memphis.

Several years ago, I had the honor of being at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta for the commemoration of Dr. King’s birthday.

Dr. King had served as the pastor at Ebenezer. His father, “Daddy” King, had served as its pastor. In 1894, his maternal grandfather, A.D. Williams, had served as that church’s second pastor.

Few people remember that Dr. King’s mother, Alberta King, was shot to death in 1974, while she was playing the organ at Ebenezer.

As I sat on the pulpit at Ebenezer, between the late Coretta Scott King, and Kerry Kennedy, the daughter of Robert F. Kennedy, I witnessed a moment of rare and raw poignancy.

Dr. King’s son, Martin III, approached Kerry, and they embraced with tears. It was at that moment that I remembered: that they had lost their fathers within two months of each other.

Six weeks after that, there were the riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. It was to be a searing, scaring spring and summer of 1968, fifty years ago.

Dr. King’s fiftieth yahrzeit coincides with the end of Pesach. In fact, Dr. King’s great religious genius was this: he created the civil rights movement as a living midrash on the Exodus from Egypt.

Dr. King did not invent that rhetorical move. It had, since the days of the Civil War and before, been part of black preaching. It was the curriculum of what they used to call Negro spirituals like “Go Down, Moses.” Black slaves looked at our experience, and they felt it, and they identified with it – and they wanted that story to be their story as well.

Dr. King went several steps beyond that. Dr. King opened the Bible (we might even say that he opened the Haggadah), and he started handing out parts.

- When he looked for people to play Pharaoh, he gave the part to southern racists – in fact, to the entire social system that shaped America.

- When he looked for people to play the Israelites leaving Egypt, he gave the part to his own people.

- When he looked for someone to pay the part of Moses – no, Dr. King did not need to look for a Moses. He did not seek that part. That part sought him.

His colleague, Ralph Abernathy, routinely introduced him as the “Moses of the twentieth century.”

In 1957, Dr. King had traveled to Ghana, just in time to celebrate its independence. That journey would turn out to be a transformation journey for Dr. King.

There, he witnessed the birth of a nation. There, he met Kwame Nkrumah, the first Prime Minster of Ghana.

He saw how Nkrumah addressed his people on the eve of their independence, and how Nkrumah could have chosen to wear a suit, and a tie – but instead, he dressed himself in the clothing that he had worn in prison.

In the sermon that Dr. King delivered upon his return from Ghana, he said that he had seen a nation unfold before his eyes (as the nation of Israel was born on the shores of the Red Sea).

Dr. King understood what Moses understood when he stood before Pharaoh — that “the oppressor never voluntarily gives freedom to the oppressed.”

“There seems to be a throbbing desire,” Dr. King said, “there seems to be an internal desire for freedom within the soul of every man.”

Dr. King went beyond Moses. He would come to embrace the prophetic mission in its widest and broadest sense. Dr. King believed that the essence of the biblical prophet was the ability to see the world and to preach from a place of “prophetic maladjustment.”

At Dr. King’s funeral, King’s mentor, Benjamin Mays, offered these words:

If Amos and Micah were prophets in the eighth century B.C., Martin Luther King, Jr. was a prophet in the twentieth century.

If Isaiah was called of God to prophesy in his day, Martin Luther was called of God to prophesy in his time.

If Hosea was sent to preach love and forgiveness centuries ago, Martin Luther was sent to expound the doctrine of non-violence and forgiveness in the third quarter of the twentieth century.

If a prophet is one who interprets in clear and intelligible language the will of God, Martin Luther King, Jr. fits that designation.

If a prophet is one who does not seek popular causes to espouse, but rather the causes he thinks are right, Martin Luther King qualifies on that score.

Like the biblical prophets, he realized that there was a spiritual illness at the very heart of his people.

By our silence, by our willingness to compromise principle, by our constant attempt to cure the cancer of racial injustice with the Vaseline of gradualism, by our readiness to allow arms to be purchased at will and fired at whim, by allowing our movie and television screens to teach our children that the hero is one who masters the art of shooting and the technique of killing, by allowing all these developments, we have created an atmosphere in which violence and hatred have become popular pastimes.

Let me conclude by reflecting on how Dr. King would have, and in fact, did, address the Torah portion for the final day of Pesach – the song at the Sea, the parting of the waters of the Sea of Reeds, the closing in of the waters on the Egyptian soldiers, their bodies lying dead upon the shore.

If that image troubles you, it troubled Dr. King as well. Recall that he was a pacifist, and pacifists would not have liked that particular scene.

In his sermon “The Death of Evil upon the Seashore,” which he delivered at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in 1956, Dr. King offers us a new understanding of that scene.

This story symbolizes something basic about the universe. It symbolizes something much deeper than the drowning of a few men, for no one can rejoice at the death or the defeat of a human person. This story, at bottom, symbolizes the death of evil. It was the death of inhuman oppression and ungodly exploitation.

The death of the Egyptians upon the seashore is a glaring symbol of the ultimate doom of evil in its struggle with good. There is something in the very nature of the universe which is on the side of Israel in its struggle with every Egypt. There is something in the very nature of the universe which ultimately comes to the aid of goodness in its perennial struggle with evil.

It is now 62 years since he delivered those words; fifty years since he has been dead.

I daresay that Dr. King is now in heaven. He looks down upon the young people and their allies who are even now marching in our streets, young people and their allies who are even now changing this nation – and he is saying: I recognize that move. I recognize that marching.

Dr. King would say: “We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now.”