My literary hero has died.

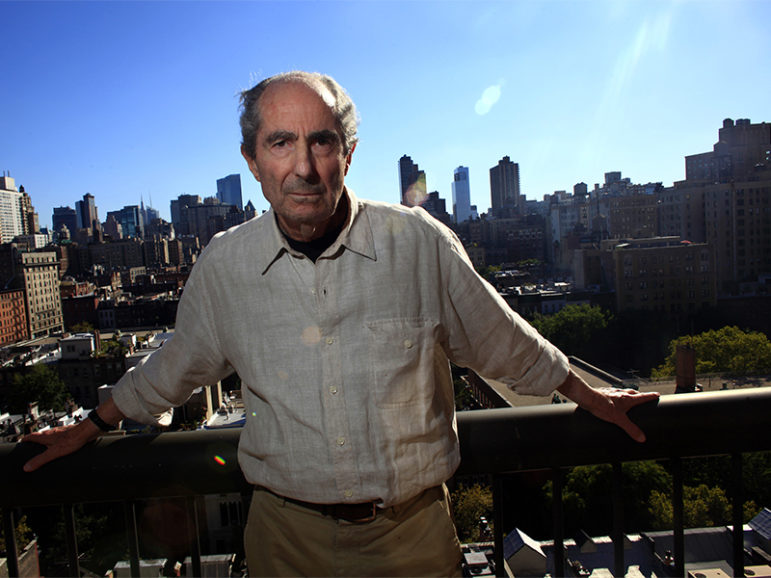

Philip Roth, the preeminent Jewish writer of our time, died yesterday at the age of 85.

Let me begin by telling you two stories.

The first story.

Several decades ago, when I was serving as a rabbi in Miami, a secretary knocked on my door.

“There’s a Mr. Roth here to see you.”

“Who is Mr. Roth?” I asked.

“Philip Roth’s father.”

At which point, the cantor, of blessed memory, said: “I would think that it would be much more interesting to meet the mother.”

I went outside to greet Mr. Roth. “Rabbi Salkin,” he said, “I understand that you gave my son’s latest book a wonderful review at a Sisterhood meeting recently.”

“Well, sir, your son has given many people a lot of pleasure over the years.”

He gave me a look that, if translated, would have said: “If you only know how much heartache I have endured….”

“Rabbi, I would like to give you an autographed copy of that book.”

He handed me a copy of The Ghost Writer, which remains one of my favorite Roth books.

After I thanked him, I went back into the meeting, opened the book, and howled with laughter.

The book was inscribed: “To Rabbi Salkin. Your friend, Herman Roth.”

(I have since found out that this was a common practice of the elder Roth — except that he usually distributed copies of Portnoy’s Complaint).

The second story.

It was the late 1980s. I was with a fellow rabbi, shopping at the general store in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He pointed out a shopper, and asked me: “Is that a colleague of ours?”

I looked at the man in question.

“Not unless Philip Roth has suddenly become a rabbi.”

We approached him, and said hello.

“So, what do you guys do?” he asked.

The words “We are rabbis…” had barely left my lips when he aerobically ran out the door.

I suppose that the years had somehow taught him to be afraid of rabbis.

He need not have been. In fact, Philip Roth has been at the center of my teaching and even my preaching throughout my career.

Here are some of my favorite Jewish moments in the Philip Roth oeuvre. There are too many to count; let this be an appetizer (and no doubt, you will have your own as well).

Let’s start with his first literary offering, Goodbye Columbus, published in 1959.

The Jewish establishment had called the young writer on the carpet for his portrayal of nouveau riche Jews (that thunder would be repeated, at a much louder volume, for Portnoy’s Complaint). Some would call him a traitor to Judaism — even, years later when the phrase became fashionable, a self-hating Jew.

Hardly. Read the novella and the short stories.

- In “Goodbye Columbus” itself, Roth castigated the vacuousness and anti-intellectualism of the emerging Jewish upper middle class. The description of the geographical and sociological journey west from Newark to Short Hills is breath-taking.

- In “The Conversion of the Jews,” Roth offers us a young boy threatening to jump off the synagogue roof unless the fretting Jews on the street agree that it would have been possible for God to make a child without intercourse. The best line in the story: “You should never hit anybody about God.”

- In “Eli The Fanatic,” Roth is criticizing the assimilated Jews of a leafy Westchester town who want to expel a yeshiva of Holocaust survivors from their community — precisely because their presence in that town embarrasses them and reminds them of the European past.

A self-hating Jew? Hardly.

A critical Jew.

From there, it is an easy walk to The Ghost Writer. Nathan Zuckerman is a young writer who is Roth’s literary doppelganger, and, like Roth, has produced a work that has scandalized both his family and the Jewish community.

Nathan visits an older Jewish writer (Bellow? Malamud?) in the Berkshires.

There, Zuckerman encounters a mysterious young girl, who seems to be the older writer’s lover.

Zuckerman imagines that the girl is Anne Frank, who has miraculously survived the Shoah.

He imagines taking her as his girl friend, and then fiancee, and introducing her to his family. “‘Anne, says my father — the Anne? Oh, how I have misunderstood my son. How mistaken we have been!'”

As if the only way that Zuckerman could redeem himself from charges of Jewish betrayal is to marry the greatest Jewish martyr of our time.

And finally — The Plot Against America.

Here, Roth offers us a grim counter-history — as dark as Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle. Charles Lindbergh, the aviator and anti-Semite, rises to the American presidency. Thus, subtly and slowly, anti-Semitic policies, including deportations of urban Jews to rural areas, begin — all witnessed through the eyes of young Philip’s family in Newark.

Roth had done his homework. The 1930s was a hateful era in America. Anti-Semitic and fascist venom flowed freely — from Lindbergh, and Father Charles Coughlin, and the admirers of Henry Ford.

In fact, Roth imagined an America that could have been — had it been offered official sanction from the very top of the power structure.

In that sense, Roth was prescient. Witness the small and large assaults on American democracy and values over the last eighteen months.

There is more. There is so much more.

True — he never won the Nobel Prize for literature.

But, right about now, Bellow and Malamud — and even Tom Wolfe — are greeting him in heaven.

They are showing him the volumes that he wrote, and they are saying: “Here, Philip. Here is your Book of Life.”