(RNS) — On the morning after a dozen boys were rescued from a Thailand cave, hymn writer Carolyn Gillette contrasted the jubilation about their survival with the despair over children being separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border.

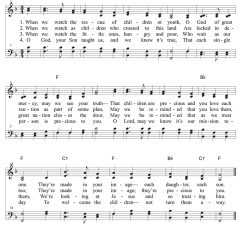

As she’s done for two decades, the Presbyterian Church (USA) minister from Philadelphia started writing new stanzas to a familiar tune. This time, it was “When We Watch the Rescue” to the tune of “Away in a Manger.”

“It’s wonderful that we will cherish one group of children — and we should — but we should cherish every child,” said Gillette of the meaning behind her new hymn. Her second verse reads:

“When we watch as children who crossed to this land

Are locked in detention as part of some plan

May we be reminded that you love them, too;

They’re made in your image; they’re precious to you.”

The hymn, along with others by composers seeking reduction of fossil fuels or provision of clean water, is an example of the music of protest in the age of Trump. Just like the songs of the civil rights movement decades ago, old and new tunes are often sung and written by people of faith. They sometimes have traditional stanzas that mention God or frame calls to action in secular terms that musicians view as a way of evoking God and government to bring about a better world.

The Hymn Society released a new collection last year called “Singing Welcome” about “hospitality to refugees and immigrants” that includes a South African freedom song, a chant from Palestine and a chorus from Mexico. The revitalized Poor People’s Campaign, which brought thousands to the National Mall in June to continue a mission of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., has its own songbook that features a contemporary song called “Somebody’s Hurting My Brother.”

“If we say that God has no hands and feet, then we’re the hands and feet,” said theo-musicologist Yara Allen, who composed that song after hearing testimonies of people of color with cancer who lived near a Duke Energy plant’s coal ash dump in North Carolina.

She cited the example of activists changing lyrics in the spiritual “Wade in the Water” from “God’s gonna trouble the water” to “We’ve got to trouble the Congress” as a way “we use that same music that connects people with the God of their understanding to what our civic responsibility is.”

Musicians and scholars who focus on sacred music have noticed how it’s increasingly in the air, from public parks to courthouse steps, as part of a soundtrack for today’s social movements. And they’re eager to understand what’s happening. In July, the Hymn Society’s annual meeting focused on “Sacred Song and the Public Square.” In September, Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Ga., plans to host a conference on “how worship embodies and shapes us for justice.”

Harry Plantinga, director of Hymnary, a 10-year-old online index of hymnals, said the Hymn Society’s conference — held in St. Louis, where the Black Lives Matter movement developed — featured speakers including a Cuban hymn writer and the publisher of African-American hymnals whose songs speak to injustice in the Americas.

“For hymns to be relevant and to sort of take root they always respond to the current situation on the ground in whatever environment they’re in,” he said.

Carolyn and Bruce Gillette at a Families Belong Together rally in Philadelphia on June 30, 2018. Photo courtesy Carolyn Gillette

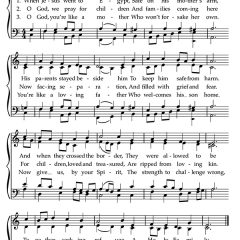

In June, Gillette wrote “When Jesus Went to Egypt,” to the tune of “O Sacred Head Now Wounded,” her lament comparing the plight of immigrant children with Jesus being able to stay with Mary and Joseph when they crossed a border. It was sung at Indianapolis’ Christ Church Cathedral, which made headlines for its front-lawn display of Holy Family statues in a detention cage. The church’s Hispanic associate minister of music translated Gillette’s words into Spanish.

Gillette said the tradition of hymns, or “sung prayers,” being sent to publishers for future hymnals may continue but the internet is allowing people to spread current-events compositions faster.

“They’re writing about them, they’re singing about them and they’re sharing them with others on the internet, on the subway,” she said. “I think it’s more of a grass-roots kind of effort.”

The Rev. Abby Mohaupt, moderator of Fossil Free PCUSA, said hymns by composer Matthew Black helped guide the feet of marchers who walked more than 200 miles to the Presbyterian Church (USA) General Assembly in June. Singing these hymns reminded them that they were both people of faith and activists.

Black’s hymn “In the Beginning (Lord Have Mercy)” contains a refrain about “how good” God’s creation is, reflecting the group’s campaign to urge divestment from the oil, gas and coal industries that, it says, harm the planet the most. The composer said he wrote another, “Where Your Treasure Is,” along the side of a highway, inspired by biblical texts on loving God first and Jesus’ teachings on money, which Mohaupt had used as the subject of a sermon earlier in the walk. The hymn’s upbeat, simple tune starts with these lines, which are repeated:

“Where your treasure is, there your heart will be.

You cannot love both God and money.”

“Matthew’s music helped knit our community together, buoyed our spirits on hard days, and became the elevator speeches of our movement,” Mohaupt said. “His prophetic artistry reminded us that we could add beauty to the world as we walked and as we got to know each other.”

Today’s sounds also strike a chord with historians of the protest music scene. The new tunes relate to — and combine with — music from the civil rights movement and the times of slavery, said Robert Darden, author of books on black sacred music from the Civil War and civil rights eras. Along with new songs, he has heard “We Shall Overcome” at the Women’s March and “Oh Freedom” at Black Lives Matter protests as he’s watched news broadcasts about them. At each time period, and with songs secular and sacred, people of faith were “putting God’s promises in action” as they sang and hoped for a better future.

- “When We Watch the Rescue” lyrics by Carolyn Gillette.

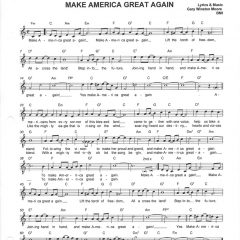

- “Make America Great Again” music and lyrics by Gary Moore.

- “When Jesus Went to Egypt” lyrics by Carolyn Gillette.

“If you were singing and believing ‘We Shall Overcome,’ you are both empowering yourself and others that God will be faithful to God’s promises,” said Darden, director of Baylor University’s Black Gospel Music Restoration Project.

Not all of today’s timely new songs from religious composers bring a protest message. The writer of one recent tune about America has focused on patriotism.

Gary Moore’s “Make America Great Again” was sung at a 2017 Fourth of July event at Washington’s Kennedy Center that included a speech by President Trump. The choir of First Baptist Dallas sang the song, which opens with the words:

“Make America great again! …

Make America great again! …

Lift the torch of freedom …

All across the land!”

Gary Moore composed “Make America Great Again.” Photo courtesy Gary Moore

Moore, a former music minister at the Dallas church, wrote the song during the 2016 presidential campaign.

“It’s not a protest against anything at all,” said Moore, now a senior associate pastor of Second Baptist Church in Houston, who noted that some hymnals include “America the Beautiful” and “God Bless America.” “It’s just more of a general call for loving the country.”

Darden said he considers some protest music, such as songs related to issues like immigration, to be more patriotic than “flag-waving” songs such as Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA.”

“When we have tens of thousands of people illegally incarcerated and separated from their children,” he said, “a song to protest that is really truer to the spirit of America.”