Some readers objected to the headline I put on last week’s column: “A court evangelical goes off the reservation.”

Tweeted one: “FYI: ‘Off the reservation’ is a racist phrase.” Commented another: “Perhaps you did not know, because it is used so widely in military applications (which ought to say something), but “off the reservation” comes from the justification for murdering Native Americans. It’s not too hard to avoid reproducing genocidal rhetoric; please consider the change.”

Let’s consider it.

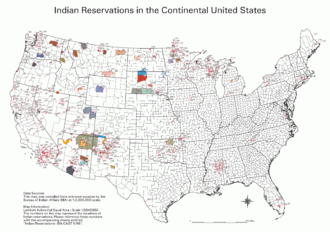

The phrase did in fact originate with reference to American Indians confined by law to territorial reservations, as in a U.S. agent’s 1878 telegram that read, “No Indians are off the reservation without authority. All my Indians are loyal and peaceable, and doing well.”

The policy of enforced confinement may have been racist, if not genocidal. But should the phrase referring to the policy be considered the same—and specifically when used, as I did, analogically?

Let’s consider a few comparable cases.

- During the intermittent persecutions of the early Church, Christians were sometimes thrown to the lions to amuse crowds seeking entertainment in Roman arenas. Does that make it anti-Christian to say, “Putting that new teacher in front of those unruly students would be throwing her to the lions”?

- “Crusade” derives from Church-sanctioned military efforts to reclaim once-Christian lands from heretics and Muslims in the Middle Ages. Is it Islamophobic to describe a fearless journalist as a “crusading editor” or to praise a civil rights leader as a “Crusader without Violence“?

- At the end of the 18th century, Catherine the Great required Jews to live within a western region of Imperial Russia known as the Pale of Settlement, making Jews who failed to do so without authorization “beyond the pale.” Should it be considered anti-Semitic to refer to, well, the use of “off the reservation” as “beyond the pale”?

- Under slavery in the South, to be sold down the river meant being separated from one’s family and condemned to a life of brutal labor. If I experience a profound betrayal, is it racist to complain that I’ve been sold down the river?

To be sure, it is normal and proper to accord communities—religious, racial, ethnic—some deference when it comes to language referring to them. If the community in question wants to be called black or African-American rather than colored or Negro, then American society by and large does so. If Jews understand “Yid” to be a slur—even if it is the Yiddish word for Jew—then the word is excluded from civil discourse.

But there are limits. Just because the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints wants to prevent his community from being referred to as Mormon doesn’t mean it will be.

So it comes down to cases. With respect to analogical usage, I’d say there are two criteria worth considering: the cultural currency of the language in question and the usefulness of the expression.

In the present case, Indian reservations are still in existence (as opposed to Christians being thrown to lions, the Church sanctioning crusades, Jews being kept within pales of settlement, and African Americans being sold down the river). Yet Indians (or Native Americans) are no longer confined to them by law.

“Off the reservation” is, admittedly, a rather tired cliché, but it has the virtue of indicating that a particular group is, for one reason or another, being kept together under pressure in one place. There is no question that evangelical leaders are currently under such pressure with respect to Donald Trump. (Just think of Russell Moore, the head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s policy arm, whose criticism of Trump has been effectively quashed.)

Bottom line: I stand by my use of “off the reservation” in this case. But I’ll think twice about using it again.