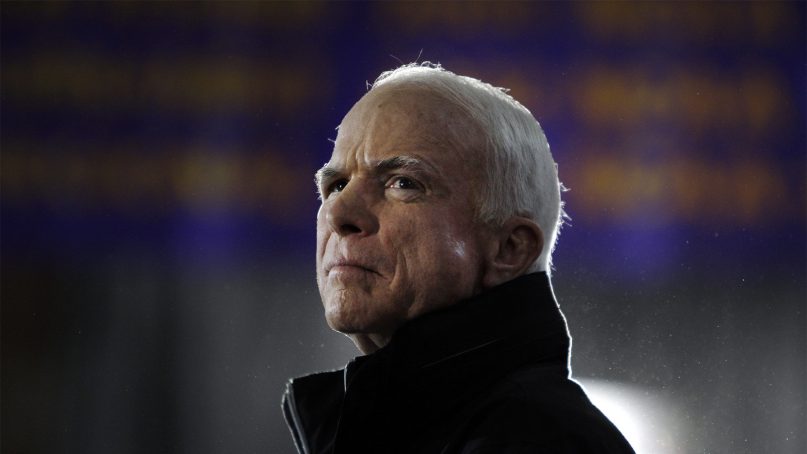

The day of John McCain’s funeral, New Yorker staff writer Vinson Cunningham characterized the late senator as “high priest” of “an American religion” and Donald Trump as “its chief heretic.” More precisely, McCain can be seen as an exemplar of what the late sociologist Robert Bellah identified as the American civil religion, Trump as promoter-in-chief of its darker alternative.

In a famous 1967 essay, Bellah argued that the American civil religion was a bona fide religious phenomenon, an”elaborate and well institutionalized” amalgam of high principles and public liturgies existing “alongside of but rather clearly differentiated from the churches.” He traced it back to the country’s founding, but fixed on Abraham Lincoln as its embodiment, thanks to Lincoln’s articulation of the country’s ideals, his bringing slavery to an end, and his personal martyrdom.

When the essay was written, the American civil religion’s foremost expression was the civil rights movement, and indeed, in the years since, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has became its best-known text, outranking the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address in its familiarity to the public at large.

But even as he celebrated what the civil religion could accomplish, Bellah was deeply concerned that the war in Vietnam would pervert it. “If the war goes on and expands, if that fatal process continues to accelerate until America becomes what it is not now and never has been, a seeker after unlimited power and empire, then Vietnam will have had a mighty and tragic fallout indeed,” he wrote. King himself was increasingly worried about the war, and found in Bellah’s essay the civil religious terminology to oppose it.

In fact, Vietnam became the crucible of a civil religious war that continues to this day. On the one hand, there’s the Bellah-King civil religion, promoting justice and equality for all, welcoming immigrants, seeking to advance democratic values around the world, and valorizing civil disobedience and dissent. On the other hand, there’s the America First civil religion that is nationalist and nativist, worried about the loss of “traditional” values and suspicious of racial, ethnic, and religious outsiders.

Barack Obama sought, with indifferent success, to reanimate the first version. Donald Trump, the anti-Obama, rode the second to the presidency. John McCain, for all his policy disagreements with Obama, was firmly in the Bellah-King camp.

He not only stood for its ideals, but the wounds and torture he suffered in Vietnam made him into a kind of living martyr for them. It is not without irony that the war that made Bellah and King so fearful for the fate of the American civil religion should have created an avatar of it. But, as McCain’s too ready support for the war in Iraq showed, a besetting weakness of the civil religion has been its tendency to overreach abroad.

In the past week, McCain’s defense of Obama during a 2008 campaign rally was recalled many times. Largely forgotten was how, eight years earlier, he had fatally injured his effort to secure the GOP presidential nomination by attacking Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson as “agents of intolerance” who “shame our faith, our party and our country.”

In his farewell letter, he declared:

We are citizens of the world’s greatest republic. A nation of ideals, not blood and soil. We are blessed and a blessing to humanity when we uphold and advance those ideals at home and in the world. We have helped liberate more people from tyranny and poverty than ever before in history. We have acquired great wealth and power in the progress. We weaken our greatness when we confuse our patriotism with rivalries that have sown resentment and hatred and violence in all the corners of the globe. We weaken it when we hide behind walls rather than tear them down, when we doubt the power of our ideals rather than trust them to be the great force for change they have always been.

It is a text that will live in the annals of American civil religion. Whether its point of view will win out is far from clear.