Imagine this:

Instead of backing a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery, President Lincoln proposes to tax ownership of human beings. “This will incentivize Southern landowners to shift to paid agricultural labor,” he tells Congress. “Freeing the slaves outright would undermine much of our reunited country’s economy.”

Or this:

After Pearl Harbor, FDR proposes to tax new automobiles, thereby incentivizing car companies to produce tanks and aircraft for the war effort. “Ordering Chrysler, Ford and General Motors to cease automobile production would be undemocratic,” he tells Congress. “And guaranteeing them a 10 percent profit, as some are suggesting, would add unnecessarily to the federal deficit.”

Ridiculous? Of course. But not much more ridiculous than proposing a tax on carbon as the solution to climate change.

This column is not unaware that the climate policy wonks and the big green organizations think taxing carbon is a great idea. Or that the Nobel Prize in economics just went to Yale’s William Nordhaus for making the case for it. Or that it has been enthusiastically embraced by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Climate, whose recent report gives us 12 years to get our act together.

So let’s stipulate that a (very high) tax on carbon would be the most economically efficient way to achieve the necessary reduction in the amount of greenhouse gases being pumped into the atmosphere. And if the sole determinant of climate policy were economic efficiency, everything would be cool.

But it’s not. Consider the politics.

In 2012, the Australian government put in place a cap-and-trade program (similar to a carbon tax) that significantly reduced greenhouse gas emissions by raising the price of carbon to $23 per metric ton. The following year, a new government bowed to public and industry pressure and did away with it.

In Washington State, where environmentalism is effectively the dominant religion, voters in the midterm elections soundly rejected a ballot measure that would have taxed oil refineries $15 per ton of carbon. In France, the yellow vest protests have forced the government to suspend a new fuel tax increase.

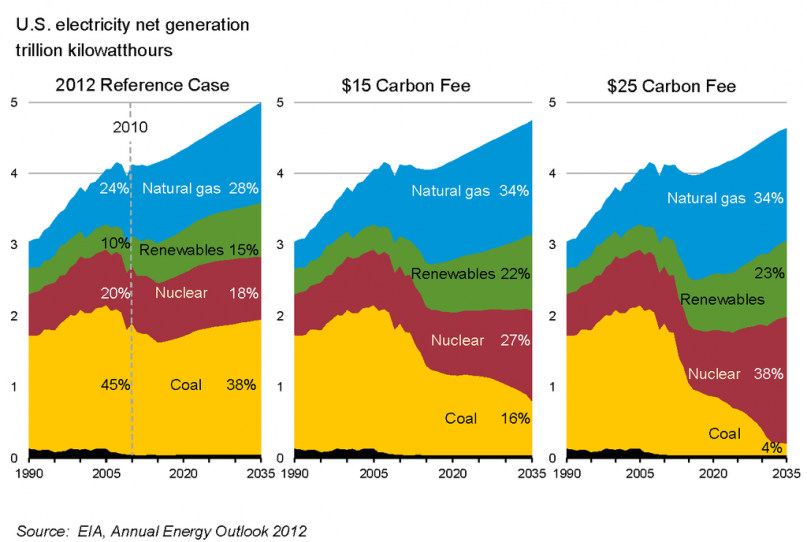

Yes, carbon taxes are in place in a number of places, but the rates are woefully inadequate to the task of keeping global warming under the new benchmark of 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. The fact of the matter is that in the real world, taxing carbon has done far less to curb greenhouse gas emissions than command-and-control policies such as mandatory mileage and fuel emissions standards.

Why?

The standard explanation is that people have a much stronger negative reaction to price increases on commodities that they purchase regularly, like gasoline and home heating fuel, than they do to the hidden costs that come with command and control—even when, as was the case in Australia, measures to compensate for the higher prices are put in place. WYSIWYG (What You See is What You Get) is the term for the psychology of this reaction, yet the wonky hope is that somehow people can be educated to understand that, even if they don’t feel it in their bones, carbon taxes are the way to go.

But this misses the deeper point. Taxation—incentivizing good behavior by jacking up the price of bad—deals with a problem indirectly, at one step removed. For some bad behavior, like cigarette-smoking, that’s ok. People are willing to put up with a tax that discourages them from a voluntary behavior they recognize as harmful to themselves and to society at large.

But where the bad behavior has led to a profound crisis, the indirect approach undermines urgency, making for cognitive dissonance: “You’re telling me that we are creating a disaster and yet all you’re proposing is to make it somewhat more expensive for us to keep doing what we’re doing? You can’t be serious!”

Nor is the dissonance merely cognitive. There’s also what might be called moral dissonance—the sense that raising the price tag is morally incompatible with the gravity of the situation. And the greater the moral imperative, the greater the dissonance.

Why are we talking about economic efficiency when, as everyone from Pope Francis on down has made clear, climate change is causing the most harm to the world’s most vulnerable?

As it is, we understand environmental protection as a moral obligation. We didn’t incentivize, we mandated clean water and clean air, we banned chemicals that destroy the ozone, we required protection of endangered species. If climate change poses a greater threat than all of the above, how can we not be taking commensurate direct action—commanding a shift to green energy, undertaking a Manhattan Project on carbon sequestration, etc.—to combat it?