WASHINGTON (RNS) — As Julián Castro officially launched his candidacy for president over the past few weeks, he invoked a certain female figure so frequently she might as well have been his running mate.

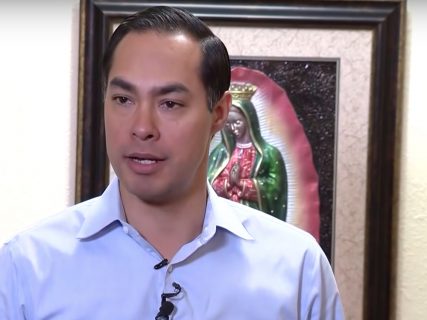

On Dec. 12, as he declared that he was forming an exploratory committee, Castro, 44, a Texan who served as U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development during President Obama’s second term, stood in front of a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Catholic Church’s patron saint of Mexico. The date was auspicious too: Dec. 12 is the Lady of Guadalupe’s feast day.

A month later Castro formally announced his campaign to a throng in Plaza Guadalupe in San Antonio, where he was mayor before going to Washington. During his speech, he made sure to point out Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church across the street.

“We were baptized just over there, at the Guadalupe church,” he said, pointing as audience members whooped and applauded.

The references weren’t an accident, he said.

“The Our Lady of Guadalupe Church was really where my story started on the west side of the city,” Castro told Religion News Service in an interview days after the event. “I was baptized there, grew up not far from there, and went to school close to there. I wanted my announcement to present to the American people who I am, and my family and I have been Catholic for generations.”

His Catholicism, in other words, is not so much about how often he goes to worship — “I can’t say I go to church as much as I’d like,” he admitted — as it is about his family, his Mexican-American heritage and his progressive values. It’s also a form of the faith that, while sometimes obscured by other popularized visions of Catholicism, is deeply familiar to growing millions of Latino voters.

Julián Castro announced he was forming an exploratory committee on Dec. 12, 2018. Video screenshot

It’s also familiar to anyone who has been watching Castro since he first broke on to the national scene in 2012.

When he delivered the keynote address that year at the Democratic National Convention — a coveted spot for the party’s rising stars — Castro peppered his speech with references to his grandmother Victoria, a Mexican immigrant who came to live with relatives in San Antonio in 1922 after being orphaned at 6 years old.

For her, he said, faith was a constant.

“I can still remember her, every morning as (my brother) and I walked out the door to school, making the sign of the cross behind us, saying, ‘Que Dios los bendiga.’ ‘May God bless you,’” Castro told the DNC crowd. He repeated the phrase as he ended his speech, putting a Spanish-language twist on a hallmark of American political rhetoric: “Que Dios los bendiga. May God bless you, and may God bless the United States of America.”

In his interview with RNS, Castro said that for immigrants like his grandmother, Catholicism wasn’t just a faith, it was a lifeline.

“The Catholic Church in many ways was a refuge for a generation of Mexican immigrants who came to places like Texas and lived a tough life,” he said. “My grandmother grew up in a lower-income household and they struggled with a lot.”

Out of that struggle, he implied, came his family’s concern for the marginalized. “For women and for people of color, those are very difficult times,” he said. “And the Catholic Church provided a sense of place and belonging and also a hope — a faith that things would get better.”

Natalia Imperatori-Lee. Photo courtesy of Manhattan College

Natalia Imperatori-Lee, an associate professor of religious studies at Manhattan College, calls Castro’s emphasis on family a “classic sort of Latino Catholic story” that speaks to a very specific kind of religious expression in which family becomes “the primary locus of … religious formation.”

It’s a faith that has less to do with institutional religion and more to do with how the divine permeates daily life.

“This is something that Latino theologians have called an emphasis on lo cotidiano, or the sacredness of the everyday,” said Imperatori-Lee, who teaches classes on Latino/Latina Catholicism.

Hosffman Ospino, director of graduate programs in Hispanic ministry at Boston College, agreed, saying Castro’s appeal to family is likely to resonate with a broad swath of Latinos.

“It’s cultural, it’s religious, but it’s also emotional,” he said. “We all — growing up in Latin America or in the United States of America as Latinos, Latinas — can make exactly that connection. We’d remember our mothers praying at home and talking about God, and talking about the church, and having these practices of popular Catholicism.”

But in an increasingly complex American electorate, Castro’s particular brand of Catholicism may have as many detractors as fans, an indicator of how multifaceted the Catholic vote has become in a nation divided by region, ethnic identity and debates over the meaning of Christianity in politics.

Imperatori-Lee said Castro’s candidacy will require “a certain kind of broadening of the definition of what it means to be a ‘real’ or ‘genuine’ Catholic” in the United States. Nor is it certain that all Democrats will be swayed by lo cotidiano: “I think it’ll be a test to see if Latino faith is recognizable to progressives as a legitimate expression of Catholicism,” she said.

Castro will have competition for the Catholic vote. Both New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and former Maryland Congressman John Delaney, who are in various stages of seeking the White House, have talked about their Catholic faith in recent weeks. Meanwhile, former Vice President Joe Biden, a proud and effusive Catholic, is also rumored to be mulling a run.

Even so, analysts say Castro has the potential to galvanize a growing national Latino vote. Hispanic Catholics make up 34 percent of all American Catholics, according to Pew Research, and roughly 64 percent of them are Democrats or lean Democratic. Most significantly, Hispanics are concentrated in the South and West, including delegate-rich California and Texas.

Julián Castro, former U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development and candidate for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, talks with voters during a campaign gathering at a shop in Somersworth, N.H., on Jan. 15, 2019. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Castro also has political bona fides likely to appeal to a wide net of Democrats. He graduated from Stanford University and Harvard Law School and in 2001, at age 26, became the youngest city councilman in San Antonio’s history. He narrowly lost a 2005 bid for the mayoralty before winning on his second try four years later. As his second term was ending, he was tapped by Obama for his Cabinet post. (Political achievement runs in the family: Julián’s twin brother, Rep. Joaquin Castro, also a Democrat, serves Texas’ 20th congressional district.)

Here, too, Castro sees faith and family at work. He ended his 2018 memoir, “An Unlikely Journey: Waking Up From My American Dream,” with an account of both brothers meeting Pope Francis at the White House during the pontiff’s 2015 visit. “I thought about how proud (his grandmother) would be that her grandsons, one a member of the president’s cabinet and the other a member of Congress, were here in this moment,” he wrote.

Today we had Cristián baptized at Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church in San Antonio. pic.twitter.com/wCREPSNLqa

— Julián Castro (@JulianCastro) September 14, 2015

He later suggested his grandmother’s experience and his own faith inform a distinctly progressive outlook, such as his passionate opposition to President Trump’s proposed border wall and the Trump administration’s family separation policy.

“In the Catholic faith and many other faiths — and even people who do not subscribe to a faith — I’ve always seen a common denominator of … treating everyone humanely,” he told RNS. “There’s no better example of where we’ve gone astray than the family separation policy that this administration ramped up last year or over the last couple of years.”

If his political heart belongs to his grandmother, Castro’s policy is perhaps more deeply influenced by his mother, Maria “Rosie” Castro, a Chicana political activist who, in addition to running for office herself, helped found La Raza Unida, a Chicano political party. She also served from 1991-1996 on the board at Network, a left-leaning Catholic social justice lobby in Washington, D.C.

In a 1996 interview with the University of Texas at Arlington Center for Mexican American Studies, Rosie Castro said Catholic teachings “had an impact on how we saw social justice, types of issues, during the Chicano movement.”

“What has always attracted me to the Catholic faith is the social justice aspect of it,” said Julian Castro. “And the vision that I articulated for the country (in his announcement speech) is very much in keeping with the social justice component of the Catholic faith, of caring for the poor, of understanding that everybody counts in our society, of trying to do what all of us can to sacrifice together so that we can lift everybody up.”

He’s been pleased, he said, to hear Pope Francis speak out in favor of immigrants, especially the pontiff’s suggestion that Trump’s border wall was not the policy of a good Christian.

Francis “is an important voice, just like I know that other religious leaders have spoken out,” he said. “I’m glad to see that.”

Trump wants folks tortured & vulnerable refugees turned away. Our faith leaders have a strong role to play against this. We all do. #resist

— Julián Castro (@JulianCastro) January 26, 2017

But Castro, whose children are baptized Catholics and attend Catholic schools, diverges sharply from Catholic orthodoxy on significant points.

He was the first mayor to serve as grand marshal of San Antonio’s Pride parade, in 2009. In 2013 he signed a city ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, and while serving as HUD secretary he spoke at LGBTQ advocacy group Human Rights Campaign’s 2016 conference. And last year he delivered remarks at a Planned Parenthood luncheon in South Texas.

While most American Catholics share Castro’s liberal leanings, supporting same-sex marriage and believing abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to Pew Research, Castro’s family-based Catholicism may irk some more conservative Catholics in eastern cities and the Midwest. Nor will his social-justice Catholicism gain him followers among those who focus narrowly on church prohibitions regarding abortion and sexuality.

Hosffman Ospino. Photo courtesy of Boston College

Ospino said Castro’s faith may not even guarantee universal loyalty from Hispanics, especially the younger generation. Ospino pointed out that the emerging generation of U.S.-born Latinos is informed not only by other religious traditions, but by the secularism that is endemic among millennials and Generation Z.

“Eventually he will need to nuance those connections to religion, because they may appeal to a certain population, but perhaps not for the majority of those (Latino Catholics) who are U.S.-born,” Ospino said.

For his part, Castro is quick to cite the importance of those who claim no faith, but he made a point to lift up religious progressives.

“The issue of religion and politics over the last 40 years has been principally dominated by the right, and I’m not quite sure why,” he said. “There are many progressives who are also people of faith. I wish that more attention were spent on how they see the world.”

He also suggested religious leaders will be key to the larger social changes he hopes to set in motion.

Shortly after Trump’s election in 2016, Castro delivered the plenary address at the American Academy of Religion conference, an annual gathering of religion scholars that convened in San Antonio that year. He called on those present to “embrace the path of light” during the Trump administration and “to help each other remember the God-given potential in every human being.”

He later added: “Religion is not now and has never been about the status quo — it is about getting better despite our flaws.”

For now, Castro seems confident voters will respond to his family-centered faith.

“Guadalupe has always served as this sort of icon of Mexican identity as much as it is an icon of Catholicism in the Americas,” said Imperatori-Lee. “It’s refreshing to see that at least one presidential candidate is capable of owning that identity in full, in all its specificity and authenticity.”