(RNS) — Last month, I attended a witches’ gathering.

Technically, it was a full moon ritual – an open-to-the-public event at Catland Books, an occult store in Bushwick, Brooklyn, designed to celebrate January’s “Blood Wolf” Moon, to “gather under this powerful light and explore energy of the first full moon of the new year … invoking the hungry wild nature, heightening instinctual senses, and inhabiting the archetypes of both the hunter and hunted.”

Nearly all of the event’s 30-odd attendees, who had paid $20 a pop to attend, appeared to be under 35. Most, though not all, were white and bore pink hair, Goth accessories or some variation of latter-day Brooklynite, countercultural style.

And while not everyone present was necessarily a practicing Wiccan or pagan — the proceedings certainly required no specialized metaphysical knowledge or affiliation — all of us were asked by the mistress of ceremonies to chant the names of ancient Roman moon goddesses Diana, Luna and Lucina (Juno), as well as to meditate to a poem written about a “wild god” whose attributes mirrored that of the Celtic horned god Cernunnos.

We breathed out “negative energy” into a Mason jar filled with the herb belladonna, picked from Catland’s own garden. We received a blessing from the ritual’s facilitator, Catland’s co-owner Melissa Madara, who passed a moonlike selenite orb around the room.

As I went through the paces, I wondered: Was I attending a religious ritual? A guided meditation? A spell? A social club?

On reflection, I realized I was being given a pitch for social activism.

For the religiously unaffiliated, witchcraft is part and parcel of a socially progressive way of life, and at spaces like Catland, New Age spirituality is increasingly inseparable from social justice advocacy. “Witchcraft” is no longer the fringe spiritual practice it once was but a political marker of resistance.

You could see this over the summer at Catland, as the store hosted a “Hex (Brett) Kavanaugh” event during the Supreme Court justice’s confirmation hearings. Or just go on Facebook, where several thousand self-proclaimed witches hex Donald Trump monthly.

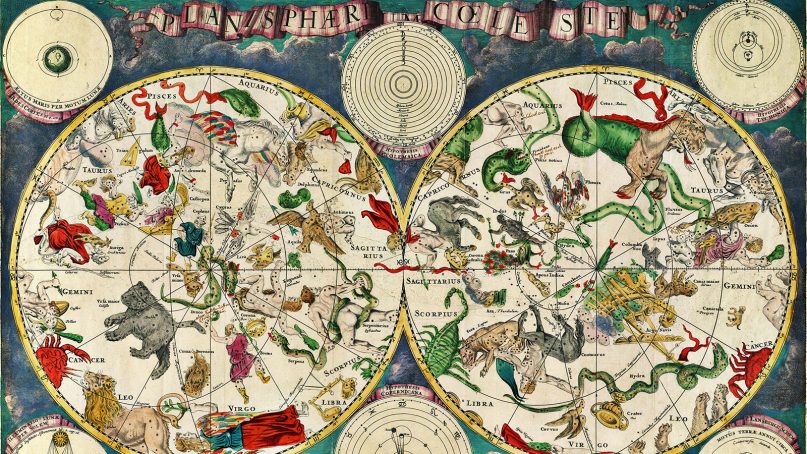

Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

But at Catland, one can also buy a zine about the ethics of cursing by Dakota Stalkfleet — aka Dakota Bracciale, the store’s other co-owner — that makes clear that curses may be used as the last resort of those without access to the criminal justice system. In other words, magic may be used to seek justice — or accountability, or plain influence — when the mainstream has failed or marginalized the practitioner.

“Folk magik is what arms the poor, the downtrodden, and the outcast,” Stalkfleet writes. “How could anyone fault me for cursing my rapist? … How could anyone blame me, let alone shame me for seeking to be the arbiter of my own justice by cursing that evil made?”

According to Stalkfleet, contemporary witch culture is a reflection of wider transitions in feminism. While the New Age movement of the 1960s and ’70s tended to be largely white and geared toward a celebration of the “divine feminine,” contemporary witchcraft is more concerned with tearing down gender divisions altogether.

To the extent the female is celebrated at all, it is as a force to be wielded against the powers that be. Kristen J. Sollee, author of “Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring the Sex Positive,” told The Guardian in 2017: “To me, the primal impulse behind each of these contested identities is self-sovereignty … witches, sluts, and feminists embody the potential for self-directed feminine power, and sexual and intellectual freedom.”

If that sounds dark, it’s meant to be: Insisting on “positivity” and “light” is for those who want to keep up the barriers of class and racial privilege.

“This demand for constant ‘love and light’ and ‘to do no harm’,” Stalkfleet writes, “is nothing more than the treacherous vile manifestations of misogyny, racism (specifically anti-blackness), classism, transphobia, and various other forms of oppression in the spiritual realm. Do not fall for it.”

It’s unclear exactly how many witches there are in America. In his 2015 book,”Witches of America,” Alex Mar suggests that the number of people practicing some form of witchcraft hovers around a million. (For comparison, there are about 1.2 million Buddhists, 2.4 million Hindus and 4 million Jews in America.) While still far from being a majority religion, these objectors to the “system” seem to be reaching some sort of critical mass.

So while witchcraft/witch culture has become an anti-capitalist platform for #resistance, it has also become a highly marketable aesthetic. As Corin Faife wrote in his BuzzFeed essay “How witchcraft became a brand,” the handicraft and vintage selling platform Etsy returns 28,000 results for the search term “witchcraft.” The Instagram hashtag #witchesofinstagram yields a staggering 700,000 results.

From subscription boxes offering spell supplies to online stores proffering decoratively spooky taxidermy, witchcraft is big business, albeit one that, in many cases, privileges the labor of small woman-owned businesses over that of big-box corporations.

But at Catland, the rituals felt less like Instagram fodder than like the building blocks of a new form of social interaction. The majority of the evening was spent breathing and chanting in unison, ultimately sharing food in a “feast” of country bread, garlic-and-onion broth and oranges. People passed food around, made conversation, drank Madara’s homemade healing tea. My neighbor told me she’d been interested in magic for a while, but only recently had dared to “seek out community.”

While we were encouraged to take photographs of the altar at the beginning of the evening and, yes, they did later show up on Instagram, I recognized that Catland’s post-ritual meal was as vital as the coffee hour that follows the Episcopal service I attend — the one that we Episcopalians only half-joke is “our real communion.”