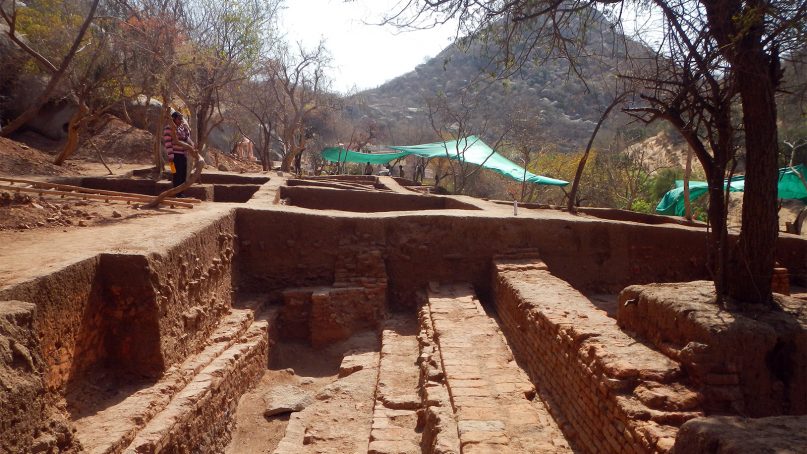

A Buddhist stupa atop Dhagolia hill in Gujarat’s Taranga range was excavated in May 2018 by the Archaeological Survey of India. Photo courtesy of ASI

VADNAGAR, India (RNS) — For generations, folk tales passed down by northern Gujarat’s nomadic goat herders described an ancient well atop Dhagolia hill in the Taranga mountains.

Then, last May, Abhijit Ambekar, a deputy superintending archaeologist with the Archaeological Survey of India, hit upon something that corresponded to the herders’ stories while excavating the weather-beaten site.

“It was like unraveling a mystery in layers. We found a structure that resembled a Buddhist stupa about 8 meters in diameter,” says Ambekar.

“There were tiers of burnt bricks, chipped stones and small boulders, which may be dated as far back as A.D. 1.”

A Buddha head found in Naderdi village in the Mehsana district of Gujarat in western India. Photo courtesy of ASI

Besides the obvious historical appeal, Ambekar’s find has become a political curiosity in India. Vadnagar, an arid village dotted with acacia shrubs, is where India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, grew up. As he faces a tight election in which voting begins Thursday (April 11), Modi, the leader of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, has avidly supported tracing Buddhism’s footprints in Gujarat’s Mehsana district.

Spurred by Modi’s interest, the archaeologists have excavated a large stupa; a Buddha head; 58 votive stupas; 65 rock shelters; an assembly hall; 22 brick platforms; habitational mounds; check dams; and other structural evidence pointing to Buddhism’s spread in the region.

While some scholars believe the spurt in excavation activities is tied to Modi’s geopolitics and zeal to placate India’s neo-Buddhists, others think he simply wants to boost tourism in his hometown.

Northern Gujarat has long been an important Buddhist center, according to the accounts of Hiuen Tsang, a seventh-century Chinese traveler and scholar who visited many sacred sites to understand Indian Buddhism practices here.

Tsang mentioned 1,000 monks of the Hinayana sect of Buddhism along with 10 monasteries flourishing in a place Tsang called “Onan To Pu Lo,” which modern scholars believe is Anandpur — the ancient name of Vadnagar.

In 1962, archaeologists at Gujarat’s Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda excavated a stupa in Devni Mori, a village near Vadnagar, where 27 terra cotta images of the Buddha were discovered. Two relic caskets at the site — one of which is believed to contain the bodily remains of the Buddha — were also unearthed and drew global attention.

Despite international fervor around Devni Mori, excavation efforts carried on sporadically for decades. Then, in 2008, archaeologists excavated a 1,200-square-meter Buddhist monastery complex in Vadnagar, dating back to A.D. 1. Led by Gujarat state archaeologist Y.S. Rawat, the team also discovered 8,000 related artifacts at the site, such as seals, crucibles, shell bangles, beads, terra cotta objects, semiprecious stones and coins.

Laborers sift through a mound of earth for antiquities near Sharmistha Lake in Vadnagar in western India. RNS photo by Priyadarshini Sen

Not far away, a centuries-old Taran Dharan Mata shrine has been found in a Buddhist cave, and excavations there have revealed stupa platforms, votive stupas, an assembly hall and other cultural artifacts pointing to Buddhism’s possible imprint here until as late as A.D. 14.

“This major discovery showed how Buddhism was embedded in the Hindu past and philosophy,” says Rawat. “It buttressed India’s position as the spiritual leader of the East.”

The discovery of this rich cultural repository drew the attention of the Dalai Lama, who inaugurated an international conference on Buddhism in Baroda, which, besides being home to the university, is a thriving trading center about 127 miles from Vadnagar. Scholars from the U.S. and the U.K., Sri Lanka, China, Myanmar and 41 other countries met to discuss Buddhist practices in the East and West.

The zeal to promote Buddhism got a boost in 2014, when Modi became India’s prime minister and became an advocate not only for Hinduism but Buddhism.

“Because of Modi’s political ascendency, ideological and intellectual engagement with Buddhism grew in a more rigorous way,” says Vishwasrao Sonawane, a retired professor of archaeology and ancient history at Maharaja Sayajirao University.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, center, greets people during a visit to his hometown, Vadnagar, Gujarat state, India, on Oct. 8, 2017. (AP Photo/Ajit Solanki)

Invitations have regularly been sent out to scholars, monks and foundation groups around the world; awareness campaigns and international conferences have become ubiquitous; and plans for an 80-foot statue of Buddha are in the works, while Buddhist nongovernmental organizations have proliferated across Gujarat.

“There are an estimated 500 NGOs and 2.5 million Buddhists in Gujarat currently,” said Bhante Prashil Ratna, president of the non-profit Buddhist organization Sanghakaya Foundation. “More people in small towns and rural areas have started turning to Buddhism since Modi’s tenure.”

A rush of funds for the development of Modi’s hometown and surrounding areas is transforming the area into a Buddhist tourist center. A Buddha circular park in Vadnagar, featuring towering statues of Shiva and Buddha blessing devotees, is just one symbol of Modi’s largesse.

“The government has put in over $11 million since 2016 for the development of Vadnagar,” said Jenu Devan, the commissioner of tourism for the Gujarat government. “The focus is on development of Buddhist and Hindu pilgrim circuits in Vadnagar and Taranga hills.”

The ongoing excavation work under Ambekar, aimed at establishing Buddhism’s unbroken presence in the region over 2,000 years, has been lauded by scholars, who approve of the BJP’s development.

An excavated prayer hall that was perhaps once used by the Buddhist monks of northern Gujarat. RNS photo by Priyadarshini Sen

“The government’s thrust is helping us get a better understanding of Buddhist religious practices in different sociocultural and political milieus across centuries,” said Amol Kulkarni, an assistant museum keeper at Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar Marathwada University in Aurangabad.

Shrikant Ganvir, an assistant professor of ancient Indian history at the Deccan College in Pune, credits Modi for reaching out to the neo-Buddhists of Gujarat, many of whom are followers of one of the most prominent low-caste 20th-century reformers, B.R. Ambedkar. Ambedkar embraced Buddhism after vociferously campaigning for an end to the discriminatory Hindu caste system.

Gaurang Jani, a sociologist at Gujarat University, says the rising caste atrocities under the BJP regime in the last two decades have led more Hindus to apply for religious conversion.

This trend has caused low-caste Dalits, who are still strongly stigmatized in Gujarat’s society, to question Modi’s sincerity in his attention to ancient Buddhist culture.

Naresh Patel, a 65-year-old retired government medical officer in Gujarat’s capital, Gandhinagar, believes Modi only stands for right-wing Hindu nationalism. “Modi has no real interest in Buddhism,” says Patel. “His zeal is only to pacify low-caste Dalits before the elections and get aid from Southeast Asian countries.”

Members of Dalit organizations protest in Mumbai, India, on April 2, 2018. Violence erupted in several parts of north and central India as thousands of Dalits, members of Hinduism’s lowest caste, protest an order from the country’s top court that they say dilutes legal safeguards put in place for their marginalized community. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

Said Ram Babu Harit, a low-caste member of the BJP’s working committee, “These excavations are only to prove that Buddhism and Hinduism weren’t mutually exclusive in India’s glorious past.”

Y.S. Alone, a professor of art and aesthetics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, believes Modi’s appropriation of Ambedkar is unlikely to sway neo-Buddhists before the elections.

Others say Modi is looking to his own future no matter what happens in the elections. “Modi may even be using Buddhism to memorialize his legacy after his political activism ends,” said activist Kancha Ilaiah.

Amid the politicking, Ambekar carries on his work unperturbed.

Every other morning, he puts his trekking shoes on to scale the Taranga hills, talks to goat herders about archaeological clues, sifts through antiquities and records them in his database.

“My work is to spotlight Mehsana on the global map,” said Ambekar, speaking of the small town where he’s currently digging. “After Devni Mori, this is one of the biggest centers where Buddhism flourished till as late as the 14th century.”