SAO PAULO (RNS) — Adherents of traditional Afro-Brazilian religions are bracing for an escalation in the already high rate of persecution and violent attacks against them as evangelical Christians have become increasingly emboldened after being credited with helping President Jair Bolsonaro’s election last fall.

In a country that is overwhelmingly Christian, less than 1% of Brazilians, or about half a million people, practice Umbanda and Candomblé, the country’s primary religions of African origin. This tiny minority accounts, however, for most of the cases of religious intolerance. In the first six months of 2018, out of 116 reports of discrimination received through a special government telephone line, 72 had Candomblecists and Umbandists as victims.

Attacks can involve assaults or vandalism at places of worship, called terreiros, verbal abuse or even physical violence. Candomblecists and Umbandists are often recognizable by their traditional garb or adornments worn on their clothes. Their worship music, generally rich in percussion, also makes their ceremonies easily identifiable.

Rychelmy Imbiriba, a Candomblé babalorisha, with other religious leaders several days after he was attacked in Salvador, Brazil, in January 2019. Photo courtesy of Eliseu Pereira

In an attack in the city of Salvador in January, Rychelmy Imbiriba, a Candomblé babalorisha, or priest, was pistol-whipped in his terreiro in what may have begun as a robbery. Six young people assaulted Imbiriba while “shouting that we were Satan worshippers and that macumbeiros (a derogatory term for Candomblecists and Umbandists) have to die,” the priest recounted.

According to Ivanir dos Santos, a scholar and Candomblé leader, believers in Afro-Brazilian religions have been suffering discrimination since colonial times. “We have been accused of sorcery and quackery. The colonizers and the republic persecuted us,” he said, referring to the First Brazilian Republic of the turn of the 20th century. “Since the 1970s, (our problem) has been some segments of neo-Pentecostalism.”

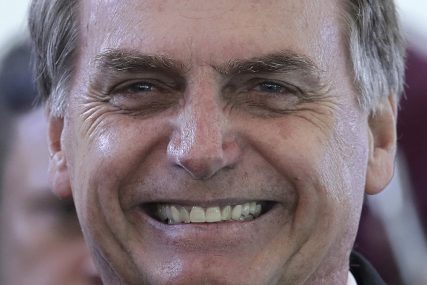

Under Bolsonaro, the climate for Afro-Brazilian believers is expected to get worse. During his campaign last year, he unapologetically dismissed the concerns of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian communities, announcing at one point, “There is no such thing as this secular state. The state is Christian and the minority will have to change, if they can.”

Brazil’s then-President-elect Jair Bolsonaro smiles during a lunch in Brasilia, Brazil, on Dec. 11, 2018. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

Since taking office, Bolsonaro has continued this line, telling the press during a visit to the White House in Washington that he is a “God-fearing man,” a quality he said he shares with President Trump.

“The most important leader in Brazil recently said during his visit to the United States that we are a Christian country, but this is a lay country. So his speech is something profoundly intolerant that aims to make the Afro-Brazilian community invisible,” said João Luiz Carneiro, an expert on Brazilian religion.

Members of the minority religions also point to Bolsonaro’s appointment of controversial evangelical pastor Damares Alves as minister of women, family and human rights — a post formerly known simply as minister of human rights.

In February, an undated video in which Alves accused a previous administration of distributing satanic handbooks to schools went viral. “A kit is arriving in schools with red candles (…) and goblets to perform sacrifices,” Alves said in the video. “What is it? It’s spiritual confusion. (…) Children are afraid to sleep at night because they are afraid of the devil.”

The association with the devil was not casual, but aimed at Afro-Brazilian religions. “The hate discourse has been intensified,” said Maria Elise Rivas, a yalorisha, or priestess.

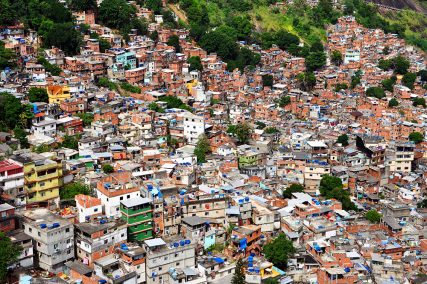

Rocinha, in Rio de Janeiro, is the largest favela in Brazil. Photo by Chen Siyuan/Creative Commons

Though the perception that persecution is increasing may be partly due to increased attention to the minority religions, observers point to more frequent reports on social media of attacks and verbal abuse.

The heightened fears result too from the phenomenon of evangelical drug lords who control entire neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, especially the desperately impoverished slums known as favelas. Two weeks ago, a gang of drug traffickers took control of an area of Nova Iguaçu, a city close to Rio de Janeiro, and expelled the local terreiro in the name of Jesus — only to transform it into a spot to sell drugs.

The Afro-Brazilian pantheon of gods and goddesses includes orishas or voduns (Umbandists additionally worship ancestral spiritual entities), to whom worshippers may offer small animals — that are cooked and eaten later. Healings involving herbs may be performed or prescribed. All these practices, which vary depending on local traditions, have been historically seen by Christians as diabolical.

“Persecution is based on the argument that such religious practices are primitive, immoral and unsanitary,” said Erisvaldo Santos, an education professor at the Federal University of Ouro Preto and an expert in religious intolerance. “For some Judeo-Christian doctrines, they are the work of the devil and should be eradicated from Brazil, so the work of God can triumph.”

Santos, a babalorisha who has been attacked himself, considers prejudice against Umbanda and Candomblé a form of “religious racism” that replaced scientific racism, common in the beginning of the 20th century, and moved to the field of social sciences, resulting in the demonization of African religious heritage.

- Women wade into the ocean with a boat filled with offerings for Yemanja, goddess of the sea, during a ceremony that is part of traditional New Year’s celebrations on Copacabana beach in Rio de Janeiro, on Dec. 29, 2018. As the year winds down, Brazilian worshippers of Yemanja celebrate the deity, offering flowers and launching large and small boats into the ocean in exchange for blessings in the coming year. The belief in the goddess comes from the African Yoruban religion brought to America by West African slaves. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

- People participate in a Candomblé religious celebration of Orisha in a temple in Salvador, Brazil. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Despite the Candomblecists and Umbandists’ small numbers, the Afro-Brazilian religions have a broad cultural impact in Brazil as it’s not unusual for Catholics, for instance, to practice Umbanda or Candomblé in what is locally called “dual membership.”

“It was common that the initiation of a person in Candomblé included a Catholic Mass at some point,” Carneiro said.

Many people are ashamed to admit their Candomblé or Umbanda leanings, choosing to public identify with a more prestigious Christian denomination. The stunning growth of evangelical churches since the 1970s, from 5% then to 22% of the population today, further skewed the traditional dynamics of Brazilian religion.

“Dual membership is very rare for evangelicals,” said Carneiro. “At the same time, Umbanda and Candomblé are a central element for most conservative neo-Pentecostals. In their Manichean battle, Afro-Brazilian religions are identified with evil.”

For Rivas, the survival of practitioners like her will be decided in the next few years. “If I could give advice to my fellow Umbandists and Candomblecists, it would be: ‘Don’t be afraid of publicly showing how good our work is. The more we retract, the more we will easily be attacked. And the neo-Pentecostals who are not prejudiced against us have to come up and say it. We need to hear their dissonant voices.”