Editor’s note: This column includes spoilers from the finale of HBO’s “Game of Thrones” series.

(RNS) — HBO’s “Game of Thrones” — the television phenomenon that for eight years has dominated Sunday night routines for millions of people around the globe — drew to a close with a deeply satisfying, spiritually intriguing finale that might have sprung from the imagination of Henri Nouwen instead of George R.R. Martin.

In the end, the one who ascends the iron throne of Westeros is neither the mightiest nor the most victorious. Instead he is a broken boy — a merciful, wounded healer who comes to reign with the help of a wise fool and the unquantifiable, mysterious power of the spiritual realm.

“Game of Thrones,” which debuted in April 2011 and ran for 73 episodes, set television ratings records around the world. The penultimate episode of Season 8 on May 12 drew a record 18.4 million viewers (a number that includes live, same-night replay and streaming viewers).

The series finale May 19 drew a record-breaking 19.3 million viewers (a number that includes live, same-night replay and streaming viewers) — the largest audience in the 47-year-old network’s history, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

In other words, people were seriously invested in the outcome of this show — the television iteration of Martin’s fantasy epic “A Song of Ice and Fire,” (which mercifully ended in neither).

Eight seasons of “Game of Thrones” have served millions of fans, whose appetites for sex, violence and revenge should have been well sated after years of bodice-ripping and backstabbing throughout the realm of Seven Kingdoms, a last meal of hearty theological ideas.

Stark family siblings Arya, left, Bran and Sansa in the final episode of “Game of Thrones.” Photo courtesy of HBO

As it turns out, the game of thrones isn’t won by anybody.

Rather, the throne in question is destroyed — melted by the white-hot grief of an orphaned dragon.

And in a choice that turns the idea of true power on its head in a wholly biblical fashion, Brandon Stark — dubbed “Bran the Broken” by Lord Tyrion Lannister — emerges as King of the Andals, Lord of the Six Kingdoms and Protector of the Realm.

What makes Bran the best choice to lead the realm? It is not his political influence or wealth or pedigree.

It’s his story.

“What unites people? Armies. Gold. Flags. Stories,” Tyrion begins in perhaps the most powerful monologue of the series. “There’s nothing in the world more powerful than a good story. Nothing can stop it. No enemy can defeat it.”

Who has a better story than Bran the Broken? A boy who was paralyzed from the waist down after Jaime Lannister pushed him out of a tower window later rises to become the Three-Eyed Raven, perhaps the most powerful spiritual character in Martin’s fictional world.

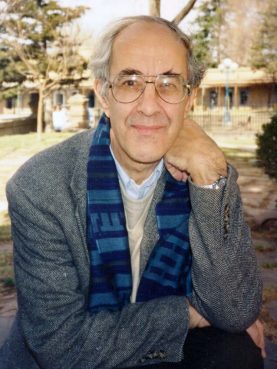

Henri Nouwen. Photo by Frank Hamilton/Creative Commons

In his seminal book, “The Wounded Healer,” late Catholic theologian Nouwen describes woundedness — and every person carries a wound, whether physical, emotional or spiritual — as a strength rather than a weakness. The greatest leaders (in any realm) are those who use their woundedness to help others.

“The great illusion of leadership is to think that man can be led out of the desert by someone who has never been there,” Nouwen wrote.

The archetype of the wounded healer is Jesus Christ.

All of the characters who emerge as “winners” in the “Game of Thrones” finale are wounded: Tyrion Lannister, Sansa Stark, Jon Snow, Arya Stark, Ser Davos Seaworth, Ser Brienne of Tarth.

And most of all, Bran the Broken.

“The boy who fell from the high tower and lived. He knew he’d never walk again, so he learned to fly,” says Tyrion, played by Peter Dinklage, in one of his several barn-burning soliloquies in the finale.

“He crossed the wall — a crippled boy — and became the Three-Eyed Raven. He is our memory, the keeper of all our stories — the wars, weddings, births, massacres, famines, our triumphs, our defeats, our past. Who better to lead us into the future?”

Bran’s first act as king is to appoint Tyrion, maligned and shunned his whole life because of his dwarfism, as “hand of the king” — essentially the chief operations officer of the kingdom.

Peter Dinklage played Tyrion Lannister in “Game of Thrones.” Photo courtesy of HBO

Tyrion, an outcast who has a morally checkered past and who has spent the last several seasons attempting to make amends and redeem himself, demurs at first.

“I don’t deserve it. I thought I was wise, but I wasn’t. I thought I knew what was right, but I didn’t,” he says.

When Grey Worm argues that Tyrion is a criminal who “deserves justice” — rather than a plumb appointment — the king agrees. He has sentenced Tyrion to a life sentence of making amends.

“He’s made many terrible mistakes,” Bran says. “He’s going to spend the rest of his life fixing them.”

Justice, mercy and grace are related ideas.

Justice is getting what you deserve. Mercy is not getting what you deserve. And grace is getting what you absolutely don’t deserve.

The “Game of Thrones” finale explored each of them.

Kit Harrington, left, as Jon Snow and Emilia Clarke as Daenerys Targaryen in the series “Game of Thrones.” Photo courtesy of HBO

Earlier in the final episode, Jon Snow — a humble, righteous man who literally was resurrected in an earlier season after being murdered — confronts Queen Daenerys Targaryen over her earlier decision to kill thousands of civilians with her fire-breathing dragon.

She wants to continue her reign of violence and terror, believing she is in the right. Jon pleads with her to consider a different path.

“You can’t hide behind small mercies,” Daenerys tells him.

“The world we need is a world of mercy. It has to be,” Snow says, before acting to end Daenerys’ reign of terror before it can continue.

For his crime, Snow later essentially is banished — sent to live out his days far from his family or the center of power.

“Game of Thrones” draws to a close with Snow riding north surrounded by a crowd of “Wildings” — outcasts considered uncivilized, violent and worthless by those in the rest of the realm.

As the camera pans through the crowd, a blade of thick, green grass pokes through the snow and permafrost. Faint buds appear on the branches of a tree, and a warm light appears to emerge on the horizon.

Whether justice, mercy or grace, it would appear that #SpringIsComing.

And the last shall be first.